The endocrine system consists of glands and organs that produce and release hormones. The numerous types of hormones affect the body in different ways and help control body functions including tissue homeostasis, growth/development, reproduction, response to stress, and metabolism.

Three of the most important hormone axes in the endocrine system that are affected by aging include growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), cortisol/dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and testosterone/estradiol.

Growth Hormone (GH) / Insulin-like Growth Factor I (IGF-I) Axis

"Somatopause" is a term used to describe the change in GH/IGF-I axis which involves a decrease in production and sensitivity to GH and IGF-I. Typically, GH secretion declines 14% with each decade of life. In the developing human body, GH from the anterior pituitary gland stimulates production and release of IGF-I by the liver, which is then transported in the blood to stimulate growth of muscle and bone.

Decreases in IGF-I signaling, GH deficiency, and GH resistance cause delayed aging and markedly extended lifespan in animal models, which is in sharp contrast to the effects of GH/IGF-I in humans. Declines in pituitary GH secretion are associated with loss of skeletal muscle mass, increased adiposity, and other detrimental effects of aging in elderly humans. The reason for the opposing actions of GH/IGF-I in different species is not presently understood.

With aging, there is a decrease in the amount of circulating GH and consequently IGF-I which results in weaker bones with a low bone mineral density (BMD). In addition to lower circulating amounts of IGF-I, the responsiveness of the bone to this protein has been shown to decrease in animal models. This decrease in responsiveness can be attributed to a decrease in IGF-I signaling pathways with advanced cell age. Binding of IGF-I to its receptors normally initiates signaling cascades involving phosphorylation of extracellular signal related kinase (ERK 1/2) and cyclin-dependent kinase (AKT). These two pathways both combine to promote osteoblast proliferation and survival.

Cortisol / Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA)

Another hormone axis that changes with aging is the cortisol/DHEA axis. The hypothalmus-pituitary-adrenal pathway plays an integral role in controlling immune function. Two adrenal hormones, DHEA and cortisol have opposing effects on immune system function with DHEA generally enhancing immunity and cortisol suppressing it. DHEA is released from the adrenal cortex in response to adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). DHEA peaks in the mid-20's and then gradually declines with aging (termed adrenopause) and can reach as low as 5% of its original level. Cortisol on the other hand remains relatively unchanged with aging, causing an imbalance in hormone levels and thus altered immune function. Glucocorticoids (GCs) such as cortisol also respond to ACTH and are released from the adrenal glands. One specific mechanism in which GCs suppress the immune system is through inhibition of an inhibitor. Nuclear factor kappa B, which is a transcription factor, inhibits the activation induced apoptotic response (programmed cell death) that becomes more prevalent with aging. GCs inhibit this transcription factor which in turn decreases inhibition of apoptosis.

Testosterone / Estradiol

Menopause/andropause refers to the decrease in production and circulation of estradiol (estrogen) in females and testosterone in males. Testosterone is a steroid hormone secreted by the Leydig cells. It can act upon many target organs resulting in development of secondary sexual characteristics and growth spurt at puberty. Estradiol is the female equivalent of testosterone and is secreted from granulosa cells. It is also a steroid that acts directly on many target organs to develop secondary sexual characteristics and prepares the uterus for pregnancy month to month.

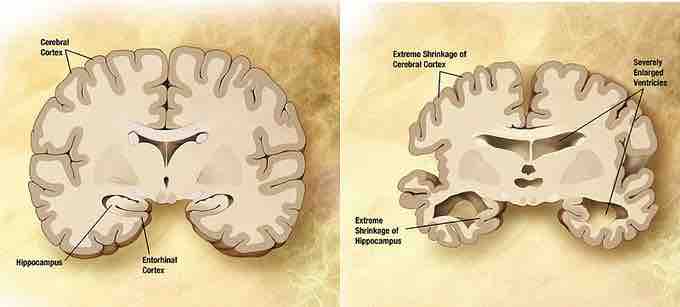

In addition to playing a role in reproduction and growth, both estrogen and testosterone demonstrate neuroprotective effects and have been theorized to play a role in reducing the effects of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in the brain . AD is characterized by age-related protein deposits in the brain. Specifically, the protein beta-amyloid (Ab) collects in vulnerable brain regions and plays a central role in the progression of AD. In vitro, cells treated with testosterone demonstrated a decrease in Ab release. However, the effects of testosterone are not as potent as that of estrogen. Estrogen acts on the nucleus of the cell by binding with the nuclear endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Once it binds to the ER, a series of activation steps are initiated resulting in the binding of the estrogen-ER complex to the estrogen responsive element (ERE). This unit mediates expression of neurotrophic factors in the brain, which contribute to neuroprotection. Further, estrogen offers an antioxidant effect at the cellular level in that it can stop oxidation induced by Ab exposure. As a result, the effects of AD are diminished in the presence of both estrogen and testosterone. Thus, a reduction in these hormones with normal aging leaves the brain more vulnerable to AD along with other pathologies. Estrogen levels take a dramatic plunge with menopause.

Normal brain vs. brain affected by Alzheimer's disease

Combination of two brain diagrams in one for comparison. In the left normal brain, in the right brain of a person with Alzheimer's disease. Estrogen and testosterone demonstrate neuroprotective effects and have been theorized to play a role in reducing the effects of Alzheimer's disease.