Development of Blood

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the bone marrow and have the unique ability to give rise to all of the different mature blood cell types. HSCs are self-renewing: When they proliferate, at least some of their daughter cells remain as HSCs, so the pool of stem cells does not become depleted. The other daughters of HSCs, myeloid, and lymphoid progenitor cells, can each commit to any of the alternative differentiation pathways that lead to the production of one or more specific types of blood cells, but cannot self-renew. This is one of the vital processes in the body. The process of the development of different blood cells from hematopoietic stem cells to mature cells is called "hematopoeisis. "

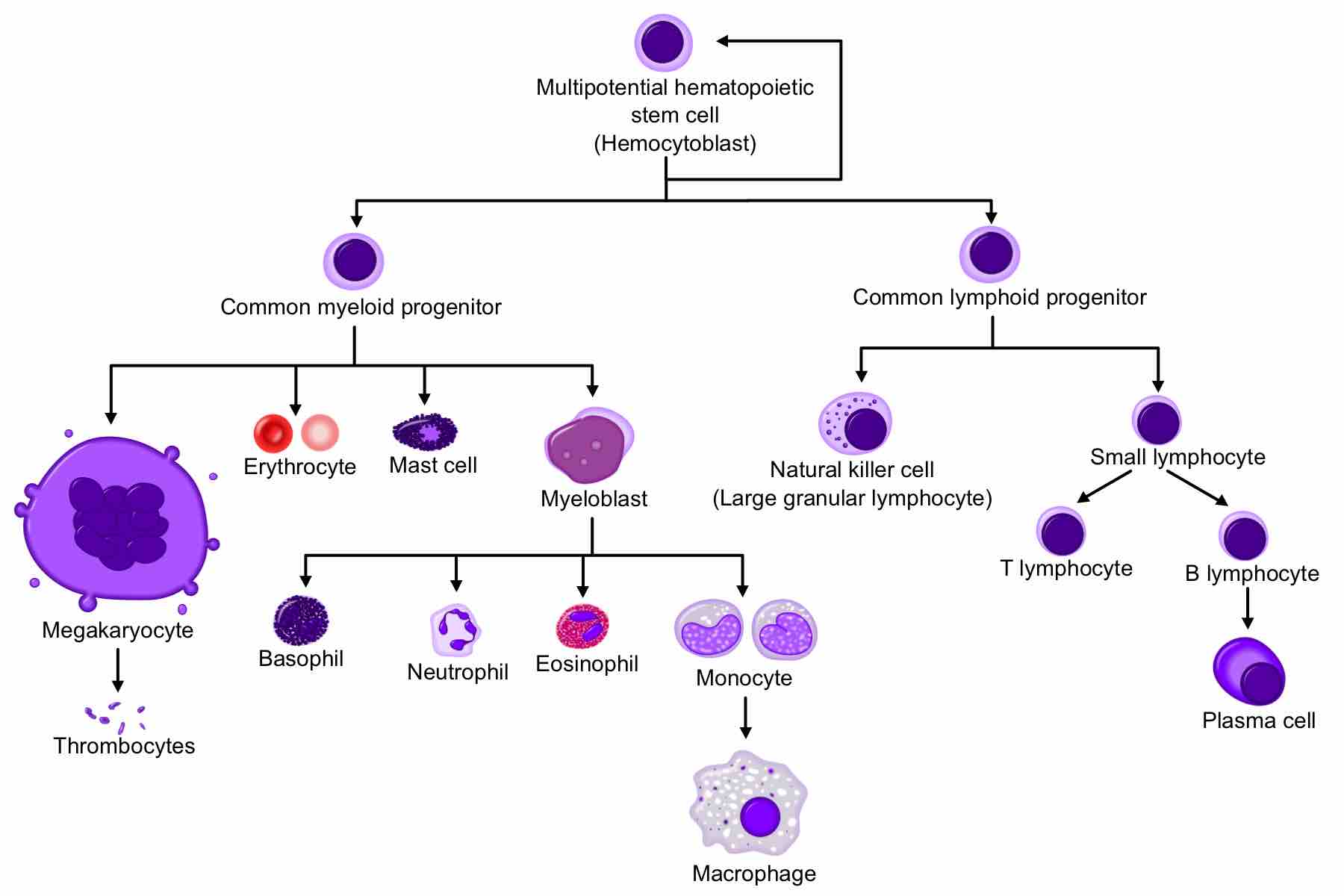

Hematopoeisis

A comprehensive diagram showing the development of different blood cells from hematopoietic stem cell to mature cells.

All blood cells are divided into three lineages:

- Erythrocytes are oxygen-carrying red blood cells; they are derived from common myeloid progenitors.

- Lymphocytes are the cornerstone of the adaptive immune system. Commonly known as white blood cells, they are derived from common lymphoid progenitors. The lymphoid lineage is primarily composed of T-cells and B-cells.

- Myelocytes, which include granulocytes, megakaryocytes, and macrophages, are derived from common myeloid progenitors and are involved in such diverse roles as innate immunity, adaptive immunity, and blood clotting.

Locations

In developing embryos, blood formation occurs in aggregates of blood cells in the yolk sac, called "blood islands. " As development progresses, blood formation occurs in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. When bone marrow develops, it eventually assumes the task of forming most of the blood cells for the entire organism. However, maturation, activation, and some proliferation of lymphoid cells occurs in secondary lymphoid organs, such as the spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes. In children, hematopoiesis occurs in the marrow of the long bones, such as the femur and tibia. In adults, it occurs mainly in the pelvis, cranium, vertebrae, and sternum.

Maturation

As a stem cell matures, it undergoes changes in gene expression that limit the cell types that it can become and moves it closer to a specific cell type. These changes can often be tracked by monitoring the presence of proteins on the surface of the cell. Each successive change moves the cell closer to the final cell type and further limits its potential to become a different cell type.

Determination

Cell determination appears to be dictated by the location of differentiation. For instance, the thymus provides an ideal environment for thymocytes to differentiate into a variety of different functional T cells. For the stem cells and other undifferentiated blood cells in the bone marrow, blood cells are determined to specific cell types by random. The hematopoietic microenvironment prevails upon some of the cells to survive and some, on the other hand, to perform apoptosis and die. By regulating this balance between different cell types, the bone marrow can alter the quantity of different cells to ultimately be produced.

Hematopoietic Growth Factor

Red and white blood cell production is regulated with great precision in healthy humans, and the production of granulocytes is rapidly increased during infection. Colony-stimulating factors (CSFs) are secreted glycoproteins that bind to receptor proteins on the surfaces of hematopoietic stem cells, thereby activating intracellular signaling pathways that can cause the cells to proliferate and differentiate into a specific kind of blood cell.

Erythropoietin is required for a myeloid progenitor cell to become an erythrocyte. On the other hand, thrombopoietin makes myeloid progenitor cells differentiate to megakaryocytes, which produce platelets.

Development of Vasculature

The development of the circulatory system initially occurs by the process of vasculogenesis. Vasculogenesis is the formation of early vasculature, which is laid down by genetic factors. Structures called "blood islands" form in the yolk sac of an embryo by cellular differentiation of hemangioblasts into endothelial cells. Next, the capillary plexus forms as endothelial cells migrate outward from blood islands and form a random network of continuous strands. These strands then undergo a process called "lumenization," the spontaneous rearrangement of endothelial cells from a solid cord into a hollow tube. The human arterial and venous systems develop from different embryonic areas. While the arterial system develops mainly from the aortic arches, the venous system arises from three bilateral veins during weeks 4 to 8 of human development.

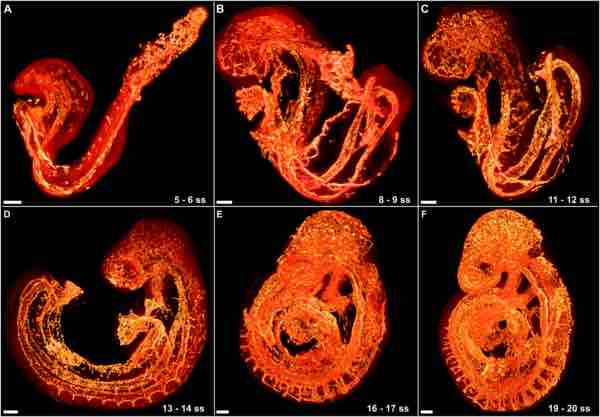

Stages of Vascular Development

The growing vasculature in the embryo is highlighted in orange.

Angiogenesis also contributes to the complexity of the initial network; endothelial buds form by an extrusion-like process which is prompted by the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These endothelial buds grow away from the parent vessel to form smaller, daughter vessels reaching into new territory. Angiogenesis is generally responsible for colonizing individual organ systems with blood vessels, whereas vasculogenesis lays down the initial pipelines of the network.