The more industrialized economy of the North aided in the production of arms, munitions, and supplies, as well as in creating financial stability and increasing ease of transportation. These advantages widened rapidly during the war, as the Northern economy grew, and the Confederate territory shrank and its economy weakened. In 1861, the Union population was 22 million while the South had a population of just 9 million. The Southern population included more than 3.5 million slaves and about 5.5 million whites, thus leaving the South's white population outnumbered by a ratio of more than four to one when compared to the North's overall population.

The Union controlled more than 80 percent of the shipyards, steamships, riverboats, and the navy. The disparity between the North and South only grew as the Union controlled an increasing amount of Southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire Southern coastline.

Excellent railroad links between Union cities allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South, which was unable to augment its much smaller rail system, repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance. The failure of Jefferson Davis to maintain positive and productive relationships with state governors damaged his ability to draw on regional resources.

"King Cotton"

During the Civil War, the leaders of the Confederacy used the slogan "King Cotton" to convince Southerners that succession from the North was feasible and desirable. The idea was that control over cotton exports would make an independent Confederacy economically prosperous, ruin the textile industry of New England, and—most importantly—force Great Britain and perhaps France to support the Confederacy militarily because their industrial economies depended on Southern cotton. The slogan was widely believed in the South, but in the end, represented a misperception of the world economy and led to bad diplomacy, such as the refusal to ship cotton before the blockade started. The British never believed in "King Cotton," and they never intervened. Consequently, the strategy proved a failure for the Confederacy—"King Cotton" did not help the new nation, but the spontaneous blockade caused the loss of desperately needed gold. The Confederacy's gamble on cotton was not only disastrous for its war efforts, but also for its economic stability.

Economic Devastation and Growth from the War

The Union grew rich fighting the war, as the Confederate economy was destroyed. The Republicans in control in Washington had a vision of an industrial nation, with great cities, efficient factories, productive farms, strong national banks, and high-speed rail links. The South had resisted policies such as tariffs to promote industry and homestead laws to promote farming because slavery would not benefit; with the South gone, and Northern Democrats very weak in Congress, the Republicans enacted their legislation. At the same time, they passed new taxes to pay for part of the war, and issued large amounts of bonds to pay for the most of the rest. They wrote an elaborate program of economic modernization that had the dual purpose of winning the war and permanently transforming the economy.

The more industrialized economy of the North continued to prosper in the years following the war, with men such as Cornelius Vanderbilt building their fortunes on transportation systems needed to sustain Northern trade.

The greatly expanded railroad network, using inexpensive steel rails produced by new steelmaking processes, dramatically lowered transportation costs to areas without access to navigable waterways. Low freight rates allowed large manufacturing facilities to grow large and prosperous with relative ease. Machinery became a major industry, and many types of machines were developed. Businesses began to operate over wide areas, and chain stores and mail-order companies developed.

In addition, an explosion of new discoveries and inventions took place, a process called the "Second Industrial Revolution," which started in 1870, just five years after the end of Civil War. The electric light, telephone, steam turbine, internal-combustion engine, automobile, phonograph, typewriter, and tabulating machine were some of the many inventions of the period. All of these inventions contributed to the rapid expansion of the economy, especially in the North.

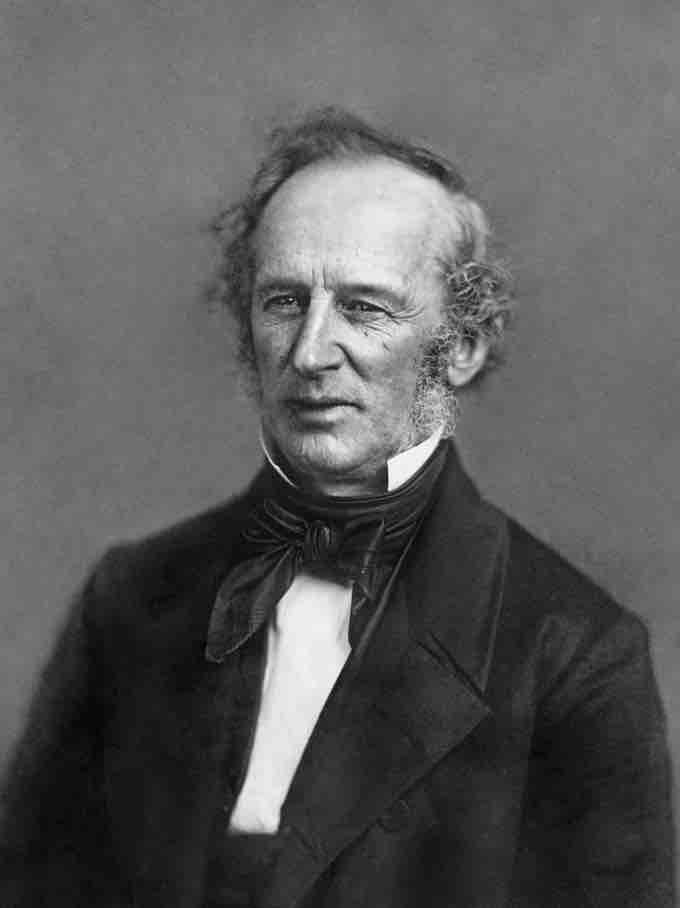

Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1794–1877

Vanderbilt, a transportation tycoon, contributed greatly to the industrial development of the North in the years immediately following the Civil War.