Reconstruction played out against a backdrop of a once prosperous economy in ruins. Most of the Civil War was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, but every Confederate state was affected, as were Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Indian Territory; Pennsylvania was the only Northern state to be the scene of major action, during the Gettysburg Campaign.

Aftermath of the War

One historian, William Hesseltine, wrote in 1936 the following about the devastation:

Throughout the South, fences were down, weeds had overrun the fields, windows were broken, live stock had disappeared. The assessed valuation of property declined from 30 to 60 percent in the decade after 1860. In Mobile, business was stagnant; Chattanooga and Nashville were ruined; and Atlanta's industrial sections were in ashes.

Farms were in disrepair, and the prewar stock of horses, mules, and cattle was much depleted, with two-fifths of the South's livestock killed. The South's farms were not highly mechanized, but the value of farm implements and machinery in the 1860 Census was $81 million and was reduced by 40 percent by 1870. The transportation infrastructure lay in ruins, with little railroad or riverboat service available to move crops and animals to market. Railroad mileage was located mostly in rural areas, and more than two-thirds of the South's rails, bridges, rail yards, repair shops, and rolling stock were in areas reached by Union armies, who systematically destroyed what they could. Even in untouched areas, the lack of maintenance and repair, the absence of new equipment, the heavy overuse, and the deliberate relocation of equipment by the Confederates from remote areas to the war zone ensured the system would be ruined at war's end. Restoring the infrastructure—especially the railroad system—became a high priority for Reconstruction state governments.

A Devastated Economy

The enormous cost of the Confederate war effort took a high toll on the South's economic infrastructure. The direct costs to the Confederacy in human capital, government expenditures, and physical destruction from the war totaled $3.3 billion. By 1865, the Confederate dollar was worthless due to massive inflation, and people in the South had to resort to bartering services for goods, or else use scarce Union dollars. With the emancipation of Southern slaves, the entire economy of the South had to be rebuilt. Having used most of their capital to purchase slaves, white planters had minimal cash to pay freedmen workers to bring in crops. As a result, a system of sharecropping was developed in which landowners broke up large plantations and rented small lots to the freedmen and their families.

Sharecropping

Sharecropping was a way for very poor farmers, both white and black, to earn a living from land owned by someone else. The landowner provided land, housing, tools, and seed (and perhaps a mule), and a local merchant provided food and supplies on credit. At harvest time, the sharecropper received a share of the crop (from one-third to one-half, with the landowner taking the rest and used his share to pay off his debt to the merchant.

The South was thus transformed from a prosperous minority of landed gentry slaveholders into a tenant farming agriculture system.

Migration of Freedmen

The end of the Civil War also was accompanied by a large migration of new freedmen from the countryside to the cities. In the cities, African Americans were relegated to the lowest paying jobs, such as unskilled and service labor. Men worked as rail workers, rolling and lumber mills workers, and hotels workers. The large population of slave artisans during the antebellum period had not translated into a large number of freedmen artisans during the Reconstruction. Black women were largely confined to domestic work and were employed as cooks, maids, and child nurses. Others worked in hotels. A large number became laundresses.

More than a fourth of Southern white men of military age—meaning the backbone of the South's white workforce—died during the war, leaving countless families destitute. Per capita income for white Southerners declined from $125 in 1857 to a low of $80 in 1879. By the end of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth century, the South was locked into a system of poverty. How much of this failure was caused by the war and by previous reliance on agriculture remains the subject of debate among economists and historians.

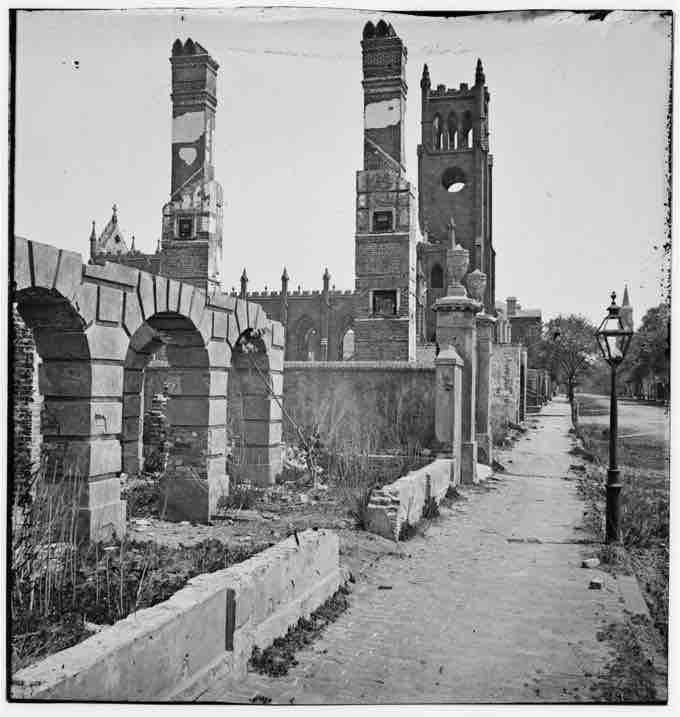

Broad Street, Charleston, South Carolina

This 1865 photograph of Broad Street, in Charleston, South Carolina, shows the devastation of the South following the Civil War.