With the Civil War approaching its end, leaders of the Union discussed how to best reincorporate the Southern states. During the Civil War, the Radical Republican leaders argued that slavery had to be permanently destroyed, and that all forms of Confederate nationalism had to be suppressed. Moderates said this easily could be accomplished as soon as Confederate armies surrendered and the Southern states repealed secession and accepted the Thirteenth Amendment—most of which happened by December 1865.

President Lincoln was the leader of the moderate Republicans and wanted to speed up Reconstruction and reunite the nation painlessly and quickly. Lincoln formally began Reconstruction in late 1863 with his Ten Percent Plan, which decreed that a state could be reintegrated into the Union when 10 percent of the 1860 vote count from that state had taken an oath of allegiance to the United States and pledged to abide by Emancipation. Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's plan, thinking it too lenient toward the Southern states. Lincoln vetoed the Radical Republicans' alternate plan, the Wade-Davis Bill of 1864, which was much more strict than the Ten Percent Plan, calling for the majority of a state's population to take a loyalty oath.

Lincoln's Final Public Speech

Three days before he was killed, President Lincoln gave a public address in which he defended his vision of Reconstruction against his detractors, argued in favor of giving freed black men full suffrage, and supported the new state constitution of Louisiana. Louisiana was to be a model for how to reintroduce Southern states to the Union. He said in this speech, "Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining, or by discarding her new State government?" Lincoln was arguing that instead of holding the Southern states to a stringent and unrealistic standard for reintroduction to the Union, the process of Reconstruction should involve working with each state where it was, encouraging its efforts to align itself with the Union, and moving forward as a unified nation. Lincoln was worried that if the efforts of Louisiana's government were rejected, not only would the rejection stymie Reconstruction, but it also would hurt the newly freed black men by saying to them, in Lincoln's words, "This cup of liberty which these, your old masters, hold to your lips, we will dash from you, and leave you to the chances of gathering the spilled and scattered contents in some vague and undefined when, where, and how." The speech infuriated Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, who declared that it would be the last speech Lincoln would ever make. Booth killed Lincoln three days later.

Andrew Johnson Takes Over for Lincoln

Upon Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, who had been elected as Lincoln's vice president in 1864, became president. Like Lincoln, Johnson rejected the Radical Republicans' program of harsh, lengthy Reconstruction and instead appointed his own governors in the Southern states in an effort to finish Reconstruction by the end of 1865.

The Republican Congress established military districts in the South and used army personnel to administer the region until new governments loyal to the Union could be established. While Congress temporarily suspended the ability to vote of approximately 10,000 to 15,000 white men who had been Confederate officials or senior officers, new constitutional amendments gave full citizenship and suffrage to former black slaves.

Background

Congress had to consider how to restore to full status and representation within the Union to those Southern states that had declared their independence from the United States and had withdrawn their representation. Suffrage for former Confederates was one of two main concerns. A decision needed to be made whether to allow just some or all former Confederates to vote (and to hold office). The moderates wanted virtually all of them to vote, but the Radicals resisted. They repeatedly tried to impose the "ironclad oath," which effectively would have prevented all former Confederates from voting. Radical Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania proposed, unsuccessfully, that all former Confederates lose the right to vote for five years. The compromise that was reached disfranchised many former Confederate civil and military leaders. No one knows how many temporarily lost the vote, but one estimate was 10,000 to 15,000.

Second, and closely related, was the issue of whether freedmen should be allowed to vote. The issue was how to receive the four million former slaves as citizens. If they were to be counted fully as citizens, some sort of representation for apportionment of seats in Congress had to be determined. Before the war, the population of slaves had been counted as three-fifths of a comparable number of free whites. By having four million freedmen counted as full citizens, the South would gain additional seats in Congress. If blacks were denied the vote and the right to hold office, then only whites would represent them. Many conservatives, including most white Southerners, Northern Democrats, and some Northern Republicans, opposed black voting. Some Northern states that had referendums on the subject limited the ability of their own small populations of blacks to vote. Lincoln had supported a middle position to allow some black men to vote, especially army veterans. Johnson also believed that such service should be rewarded with citizenship.

Senators Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Thaddeus Stevens, leaders of the Radical Republicans, were initially hesitant to enfranchise the largely illiterate former slave population. Sumner preferred at first impartial requirements that would have imposed literacy restrictions on blacks and whites. He believed that he would not succeed in passing legislation to disfranchise illiterate whites who already had the vote.

Enfranchisement of All Freedmen

The Republicans believed that the best way for men to get political experience was to be able to vote and to participate in the political system. They passed laws allowing all male freedmen to vote. In 1867, black men voted for the first time. Over the course of Reconstruction, more than 1,500 African Americans held public office in the South; some of them were men who had escaped to the North and gained educations, and then returned to the South. They did not hold office in numbers representative of their proportion in the population, but often elected whites to represent them. The question of women's suffrage was also debated but was rejected.

From 1890 to 1908, Southern states passed new constitutions and laws that disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites with new voter registration and electoral rules. When establishing new requirements such as subjectively administered literacy tests, some states used "grandfather clauses" to enable illiterate whites to vote.

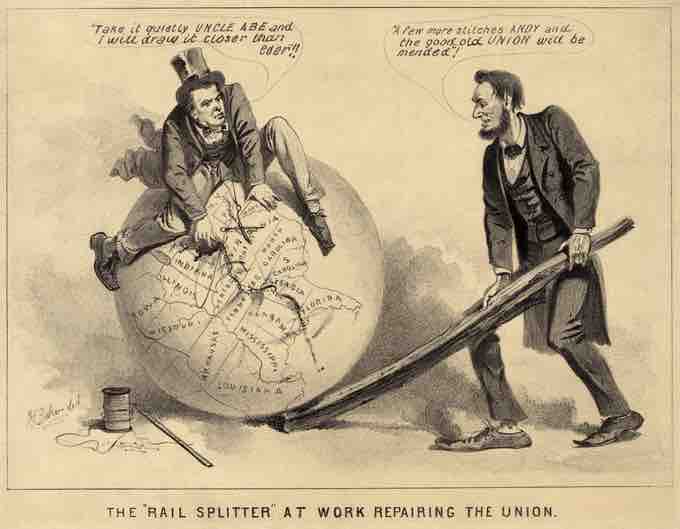

Johnson and Lincoln restoring the Union

A political cartoon of Andrew Johnson and Abraham Lincoln, 1865, entitled "The 'Rail Splitter' At Work Repairing the Union." The caption reads (Johnson): "Take it quietly Uncle Abe and I will draw it closer than ever!!" (Lincoln): "A few more stitches Andy and the good old Union will be mended!"