Tariffs in the Early National Period, 1789–1828

The Tariff Act of 1789 provided the first national source of revenue for the United States. The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1789, allowed only the federal government to levy uniform tariffs. The Tariff Act taxed all imports at rates from 5 to 15 percent. These rates were primarily designed to generate revenue to pay for the federal government's activities and the debts accumulated by the federal and state governments during the Revolutionary War. Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury under President George Washington, believed that all Revolutionary War debt should be paid in full to establish U.S. financial credibility.

The Role of Protective Tariffs

In his "Report on Manufactures," Hamilton proposed a far-reaching plan to use protective tariffs as a lever for rapid industrialization. The industrial age was just starting, and the United States had little or no textile industry, which was the keystone of early industrial societies. The British government tried to maintain their near monopoly on cheap and efficient textile manufacturing by prohibiting the export of textile machines, machine models, or the emigration of people familiar with these machines. Cloth in the early United States was nearly all hand made, which was a time-consuming and expensive process, whereas the new textile manufacturing techniques in Britain were often more than 30 times cheaper. Hamilton believed that a stiff tariff on imports would not only raise income but also "protect" and help subsidize early efforts at setting up manufacturing facilities that could compete with British products.

The high protectionist tariffs Hamilton originally called for were not adopted until after the War of 1812, when nationalists such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun saw the need for more federal income and industry. In wartime, they declared, having a home industry was a necessity to avoid shortages. Likewise, small new factories were springing up in the northeast to mass produce boots, hats, candles, nails, and other common items, and the owners of these factories wanted higher tariffs that would protect them—at least for a time—from more efficient British producers. When the Act was passed, it included a provision that allowed for a 10 percent discount on all items imported on American ships. This was done to ensure that American merchant marines would not financially suffer.

Once industrialization and mass production started, manufacturers and factory workers demanded higher tariffs. They believed their businesses should be protected from the lower wages and more efficient factories of Britain and the rest of Europe. Nearly every northern Congressman was eager to adopt a higher tariff rate for his local industry. Senator Daniel Webster, formerly a spokesperson for Boston's merchants who imported goods (and wanted low tariffs), switched dramatically to represent the manufacturing interests in the Tariff of 1824. Rates were especially high for bolts of cloth and for bar iron, of which Britain was a low-cost producer.

Controversy

The tariffs raised questions, however, about how power should be distributed, causing a fiery debate between those who supported states’ rights and those who supported the expanded power of the federal government. John C. Calhoun expressed the views of many Southerners that protective tariffs unjustly favored Northern commercial interests and Western agrarian interests at the expense of Southern producers. The North had an expanding manufacturing base while the South did not; therefore, the South imported far more manufactured goods than the North, causing such tariffs to fall most heavily on the Southern states.

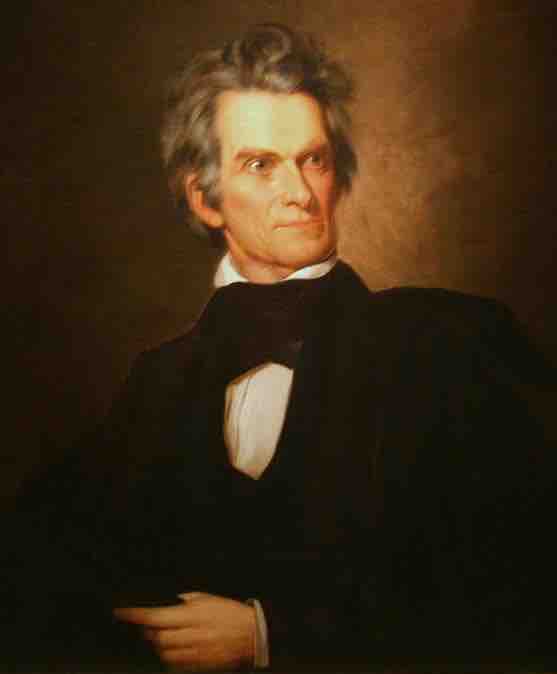

John C. Calhoun

John C. Calhoun expressed the views of many Southerners that protective tariffs unjustly favored Northern commercial interests and Western agrarian interests at the expense of Southern producers.

The Tariff of 1828

The culmination came with the Tariff of 1828, ridiculed by free traders as the "Tariff of Abominations," with import custom duties averaging more than 25 percent. Intense political opposition to higher tariffs came from Southern Democrats and plantation owners in South Carolina who had almost no manufacturing industry and imported many products with high tariffs. They would have to pay more for imports while getting less for the cotton they sold abroad. They claimed their economic interest was being unfairly injured.

Faced with a reduced market for goods and pressured by British abolitionists, the British reduced their imports of cotton from the United States, which weakened the Southern economy even more. The tariff forced the South to buy manufactured goods from U.S. manufacturers, mainly in the North and at a higher price, while Southern states also faced a reduced income from lost sales of raw materials.

Nullification Crisis

John C. Calhoun strongly opposed the tariff and urged nullification of the tariff within South Carolina. On July 14, 1832, President Andrew Jackson signed into law the Tariff of 1832, which made some reductions in tariff rates. However, the reductions were too little for South Carolina, and in November of 1832, the state adopted an ordinance of nullification and declared that the tariffs of both 1828 and 1832 were unconstitutional and unenforceable in South Carolina.

The passing of the ordinance, which later became known as the Nullification Crisis, also sparked early discussions of secession from the Union among radical factions. While the Nullification Crisis would be resolved in early 1833, tariff policy would continue to be a national political issue between the Democratic Party and the newly emerged Whig Party for the next 20 years. The Nullification Crisis is also considered a precursor to the sectional crisis that would become the Civil War.