Introduction

The Second Bank of the United States was chartered in 1816, five years after the First Bank of the United States lost its own charter. The predominant reason that the Second Bank of the United States was chartered was because the United States had experienced severe inflation and was having difficulty financing military operations during the War of 1812. Subsequently, the credit and borrowing statuses of the United States were at their lowest levels since its founding.

The Creation of the Bank

The Second Bank of the United States, like the First Bank before it, was created as part of the American System of economics. One of the policies of the American System was to create financial infrastructure in the form of a government sponsored National Bank to issue currency and encourage commerce. This involved the use of sovereign powers for the regulation of credit to encourage the development of the economy and to deter speculation.

The Second Bank provided a means for the government to regulate financial affairs. The bank was created when President James Madison and Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin found that the government was unable to finance the country in the aftermath of the War of 1812, which placed the United States in significant debt. The debt of the nation led to an increase in banknotes among private banks, and as a result, inflation increased greatly. For these reasons, Madison and Congress agreed to form the Second Bank of the United States.

After the war, and despite its debt, the United States experienced an economic boom due to the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars. In particular, the U.S. agricultural sector underwent great expansion, in part because of the damage to Europe's agricultural sector. The bank aided this boom through its lending, which encouraged speculation in land. This lending allowed almost anyone to borrow money and speculate in land, sometimes doubling or even tripling the prices of land. The land sales for 1819 alone totaled some 55 million acres. With such a boom, hardly anyone noticed the widespread fraud occurring at the bank as well as the economic bubble that had been created.

Panic of 1819 and McCulloch v. Maryland

In the summer of 1818, the national bank managers realized the bank's massive overextension and instituted a policy of contraction and the calling in of loans. This recalling of loans at once curtailed land sales and slowed the U.S. production boom, which occurred simultaneously with the recovery of Europe. The result was the Panic of 1819 and the situation leading up to McCulloch v. Maryland (1819).

During this time, Maryland adopted a policy to restrict banks by placing a tax on any bank that was not chartered by the state legislature. This tax was either 2 percent of all assets or a flat rate of $30,000. This meant that the Baltimore branch of the Second Bank of the United States would have to pay this hefty tax. The State filed suit against McCulloch, the representative of the bank, in a county court. The case made its way through the courts, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the tax by the state of Maryland was ultimately struck down.

The Bank's Decline

By the early 1830s, President Andrew Jackson had come to thoroughly dislike the Second Bank of the United States because of its fraud and corruption. Apart from a general hostility toward the banking system and a belief that specie ("hard" money of gold or silver) was the only true money, Jackson's reasons for opposing the renewal of the charter revolved around his belief that bestowing special privileges (such as government sponsorship) on banks was the cause of inflation and other perceived evils. As a result of his beliefs, Jackson is considered primarily responsible for the Bank's demise.

The Second Bank of the United States thrived on tax revenue that the federal government regularly deposited. Jackson struck at this vital source of funds in 1833 by instructing his Secretary of the Treasury to deposit federal tax revenues in state banks, soon nicknamed "pet banks" because of their loyalty to Jackson's party.

In September of 1833, Secretary of the Treasury Roger B. Taney transferred the government's Pennsylvania deposits in the Second Bank of the United States to the Bank of Girard in Philadelphia. The Second Bank of the United States soon began to lose money. Nicholas Biddle, desperate to save his bank, called in all of his loans and closed the bank to new loans. This angered many of the bank's clients, causing them to pressure Biddle to readopt its previous loan policy. This then triggered Biddle's Panic.

Some Anti-Jacksonians converted their outrage into political action. Under guidance from Webster and Clay, they formed the Whig Party in 1833. The Whigs and anti-Jackson National Republicans hoped they would gain enough seats in Congress during the election of 1836 to override a second Jackson veto, thereby extending the Bank's charter. However, their strategy was not successful, and their coalition still lacked the necessary majority in Congress following the election to extend the Bank's charter. In 1836, the Bank's charter was allowed to expire. It attempted to continue as a standard bank, but failed five years later.

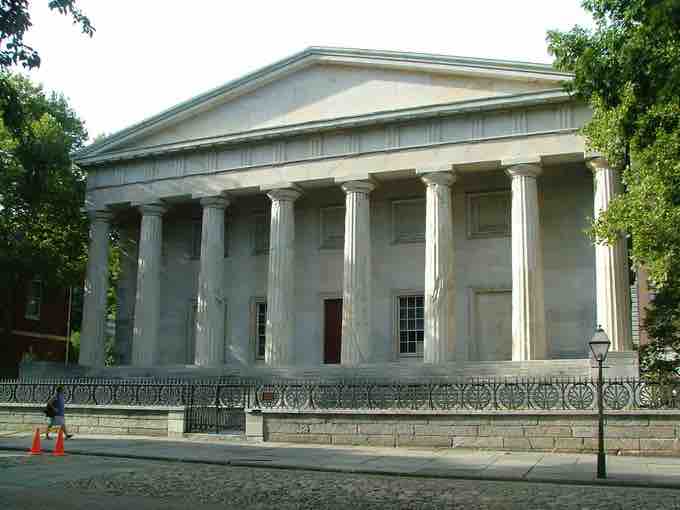

Second Bank of the United States—south facade

The south facade of the building that housed the Second Bank of the United States is located at 4th and Chestnut Streets in Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.