New Social Movements

The term new social movements (NSMs) is a theory of social movements that attempts to explain the plethora of new movements that have come up in various western societies roughly since the mid-1960s (i.e. in a post-industrial economy), which are claimed to depart significantly from the conventional social movement paradigm .

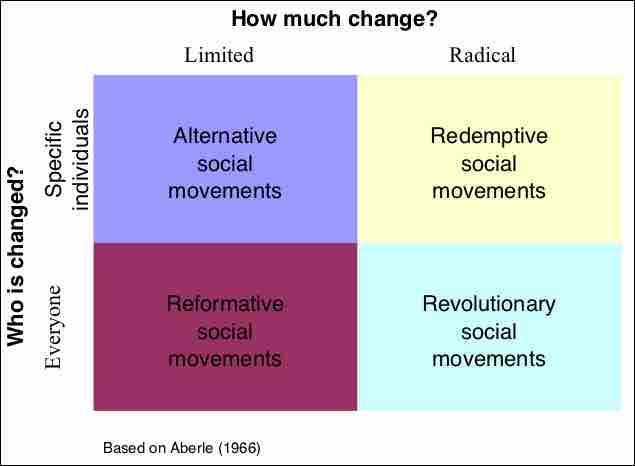

Aberle's Four Types of Social Movements

The term new social movements (NSMs) is a theory of social movements that attempts to explain the plethora of new movements that have come up in various western societies roughly since the mid-1960s (i.e. in a post-industrial economy), which are claimed to depart significantly from the conventional social movement paradigm.

There are two central claims of the NSM theory. Firstly, the rise of the post-industrial economy is responsible for a new wave of social movement. Secondly, these movements are significantly different from previous social movements of the industrial economy. The primary difference is in their goals, as the new movements focus not on issues of materialistic qualities such as economic well-being, but on issues related to human rights (such as gay rights or pacifism).

Characteristics

The most noticeable feature of new social movements is that they are primarily social and cultural and only secondarily, if at all, political. Departing from the worker's movement, which was central to the political aim of gaining access to citizenship and representation for the working class, new social movements concentrate on bringing about social mobilization through cultural innovations, the development of new lifestyles, and the transformation of identities. It is clearly elaborated by Habermas that new social movements are the "new politics" which is about quality of life, individual self-realization, and human rights; whereas the "old politics" focused on economic, political, and military security. The concept of new politics can be exemplified in gay liberation, the focus of which transcends the political issue of gay rights to address the need for a social and cultural acceptance of homosexuality. Hence, new social movements are understood as "new," because they are first and foremost social, unlike older movements which mostly have an economic basis.

New social movements also emphasize the role of post-material values in contemporary and post-industrial society, as opposed to conflicts over material resources. According to Melucci, one of the leading new social movement theorists, these movements arise not from relations of production and distribution of resources, but within the sphere of reproduction and the life world. Consequently, the concern has shifted from the production of economic resources as a means of survival or for reproduction to cultural production of social relations, symbols, and identities. In other words, the contemporary social movements reject the materialistic orientation of consumerism in capitalist societies by questioning the modern idea that links the pursuit of happiness and success closely to growth, progress, and increased productivity and by instead promoting alternative values and understandings in relation to the social world. As an example, the environmental movement that has appeared since the late 1960s throughout the world, with its strong points in the United States and Northern Europe, has significantly brought about a "dramatic reversal" in the ways we consider the relationship between economy, society, and nature.

Further, new social movements are located in civil society or the cultural sphere as a major arena for collective action rather than instrumental action in the state, which Claus Offe characterizes as "bypass[ing] the state. " Moreover, since new social movements are not normally concerned with directly challenging the state, they are regarded as anti-authoritarian and as resisting incorporation at the institutional level. They tend to focus on a single issue, or a limited range of issues connected to a single broad theme, such as peace or the environment. New social movements concentrate on the grassroots level with the aim to represent the interests of marginal or excluded groups. Therefore, new collective actions are locally based, centered on small social groups and loosely held together by personal or informational networks such as radios, newspapers, and posters. This "local- and issue-centered" characteristic implies that new movements do not necessarily require a strong ideology or agreement to meet their objectives.

Additionally, if old social movements, namely the worker's movement, presupposed a working class base and ideology, the new social movements are presumed to draw from a different social class base, i.e., "the new class. " This is a complex contemporary class structure that Claus Offe identifies as "threefold" in its composition: the new middle class, elements of the old middle class, and peripheral groups outside the labor market. As stated by Offe, the new middle class has evolved in association with the old one in the new social movements because of its high levels of education and its access to information and resources. The groups of people that are marginal in the labor market, such as students, housewives, and the unemployed participate in the collective actions as a consequence of their higher levels of free time, their position of being at the receiving end of bureaucratic control, and their inability to be fully engaged in society specifically in terms of employment and consumption.