Trait Theories of Personalities

Trait theorists believe personality can be understood by positing that all people have certain traits, or characteristic ways of behaving. Do you tend to be sociable or shy? Passive or aggressive? Optimistic or pessimistic? According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association, personality traits are prominent aspects of personality that are exhibited in a wide range of important social and personal contexts. In other words, individuals have certain characteristics that partly determine their behavior; these traits are trends in behavior or attitude that tend to be present regardless of the situation.

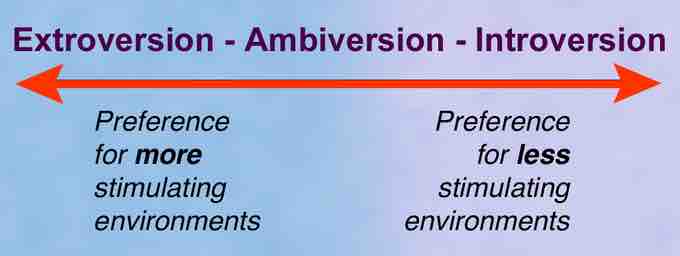

An example of a trait is extraversion–introversion. Extraversion tends to be manifested in outgoing, talkative, energetic behavior, whereas introversion is manifested in more reserved and solitary behavior. An individual may fall along any point in the continuum, and the location where the individual falls will determine how he or she responds to various situations.

Extraversion–Introversion

This image is an example of a personality trait. At one end is extraversion (with a preference for more stimulating environments), and at the other end is introversion (with a preference for less stimulating environments). An individual may fall at any place on the continuum.

The idea of categorizing people by traits can be traced back as far as Hippocrates; however more modern theories have come from Gordon Allport, Raymond Cattell, and Hans Eysenck.

Gordon Allport (1897–1967)

Gordon Allport was one of the first modern trait theorists. Allport and Henry Odbert worked through two of the most comprehensive dictionaries of the English language available and extracted around 18,000 personality-describing words. From this list they reduced the number of words to approximately 4,500 personality-describing adjectives which they considered to describe observable and relatively permanent personality traits.

Allport organized these traits into a hierarchy of three levels:

- Cardinal traits dominate and shape an individual's behavior, such as Ebenezer Scrooge’s greed or Mother Theresa’s altruism. They stand at the top of the hierarchy and are collectively known as the individual's master control. They are considered to be an individual's ruling passions. Cardinal traits are powerful, but few people have personalities dominated by a single trait. Instead, our personalities are typically composed of multiple traits.

- Central traits come next in the hierarchy. These are general characteristics found in varying degrees in every person (such as loyalty, kindness, agreeableness, friendliness, sneakiness, wildness, or grouchiness). They are the basic building blocks that shape most of our behavior.

- Secondary traits exist at the bottom of the hierarchy and are not quite as obvious or consistent as central traits. They are plentiful but are only present under specific circumstances; they include things like preferences and attitudes. These secondary traits explain why a person may at times exhibit behaviors that seem incongruent with their usual behaviors. For example, a friendly person gets angry when people try to tickle him; another is not an anxious person but always feels nervous speaking publicly.

Allport hypothesized that internal and external forces influence an individual's behavior and personality, and he referred to these forces as genotypes and phenotypes. Genotypes are internal forces that relate to how a person retains information and uses it to interact with the world. Phenotypes are external forces that relate to the way an individual accepts his or her surroundings and how others influence his or her behavior.

Raymond Cattell (1905–1998)

In an effort to make Allport's list of 4,500 traits more manageable, Raymond Cattell took the list and removed all the synonyms, reducing the number down to 171. However, saying that a trait is either present or absent does not accurately reflect a person’s uniqueness, because (according to trait theorists) all of our personalities are actually made up of the same traits; we differ only in the degree to which each trait is expressed.

Cattell believed it necessary to sample a wide range of variables to capture a full understanding of personality. The first type of data was life data, which involves collecting information from an individual's natural everyday life behaviors. Experimental data involves measuring reactions to standardized experimental situations, and questionnaire data involves gathering responses based on introspection by an individual about his or her own behavior and feelings. Using this data, Cattell performed factor analysis to generated sixteen dimensions of human personality traits: abstractedness, warmth, apprehension, emotional stability, liveliness, openness to change, perfectionism, privateness, intelligence, rule consciousness, tension, sensitivity, social boldness, self-reliance, vigilance, and dominance.

Based on these 16 factors, he developed a personality assessment called the 16PF. Instead of a trait being present or absent, each dimension is scored over a continuum, from high to low. For example, your level of warmth describes how warm, caring, and nice to others you are. If you score low on this index, you tend to be more distant and cold. A high score on this index signifies you are supportive and comforting. Despite cutting down significantly on Allport's list of traits, Cattell's 16PF theory has still been criticized for being too broad.

Hans Eysenck (1916–1997)

Hans Eysenck was a personality theorist who focused on temperament—innate, genetically based personality differences. He believed personality is largely governed by biology, and he viewed people as having two specific personality dimensions: extroversion vs. introversion and neuroticism vs. stability. After collaborating with his wife and fellow personality theorist Sybil Eysenck, he added a third dimension to this model: psychoticism vs. socialization.

- According to their theory, people high on the trait of extroversion are sociable and outgoing and readily connect with others, whereas people high on the trait of introversion have a higher need to be alone, engage in solitary behaviors, and limit their interactions with others.

- In the neuroticism/stability dimension, people high on neuroticism tend to be anxious; they tend to have an overactive sympathetic nervous system and even with low stress, their bodies and emotional state tend to go into a flight-or-fight reaction. In contrast, people high on stability tend to need more stimulation to activate their flight-or-fight reaction and are therefore considered more emotionally stable.

- In the psychoticism/socialization dimension, people who are high on psychoticism tend to be independent thinkers, cold, nonconformist, impulsive, antisocial, and hostile. People who are high on socialization (often referred to as superego control) tend to have high impulse control—they are more altruistic, empathetic, cooperative, and conventional.

The major strength of Eysenck's model is that he was one of the first to make his approach more quantifiable; it was therefore perceived to be more "legitimate", as a common criticism of psychological theories is that they are not empirically verifiable. Eysenck proposed that extroversion was caused by variability in cortical arousal, with introverts characteristically having a higher level of activity in this area than extroverts. He also hypothesized that neuroticism was determined by individual differences in the limbic system, the part of the human brain involved in emotion, motivation, and emotional association with memory. Unlike Allport's and Cattell's models, however, Eysenck's has been criticized for being too narrow.