Anemia

Anemia is a decrease in number of red blood cells (RBCs), or less than the normal quantity of hemoglobin in the blood. It can include the decreased oxygen-binding ability of each hemoglobin molecule due to deformity or lack in numerical development as in some other types of hemoglobin deficiencies.

Because hemoglobin (found inside RBCs) normally carries oxygen from the lungs to the tissues, anemia leads to hypoxia (lack of oxygen) in organs. Since all human cells depend on oxygen for survival, varying degrees of anemia can have a wide range of clinical consequences.

TYPES OF ANEMIA

Anemia is the most common disorder of the blood. There are several kinds, produced by a variety of underlying causes. It can be classified in a variety of ways, based on the morphology of RBCs, underlying etiologic mechanisms, and discernible clinical spectra, to mention a few.

The three main classes of anemia include excessive blood loss (acutely, such as a hemorrhage or chronically, through low-volume loss), excessive blood cell destruction (hemolysis), or deficient red blood cell production (ineffective hematopoiesis).

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

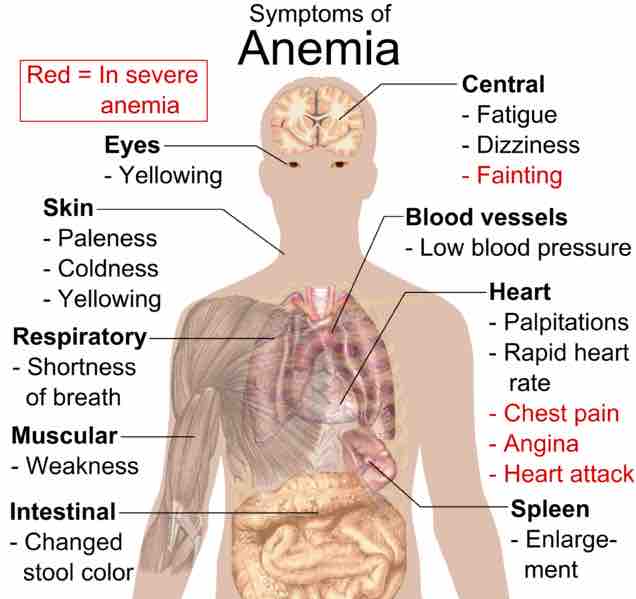

Anemia goes undiagnosed in many people, as symptoms can be minor or vague. The signs and symptoms can be related to the anemia itself, or the underlying cause. Most commonly, people report non-specific symptoms of a feeling of weakness, or fatigue, general malaise, and, sometimes, poor concentration. They may also report dyspnea (shortness of breath) on exertion.

In very severe anemia, the body may compensate for the lack of oxygen-carrying capability of the blood by increasing cardiac output. This would result in symptoms such as palpitations, angina (if preexisting heart disease is present), intermittent claudication of the legs, and symptoms of heart failure .

Symptoms of Anemia

Image displays the common symptoms of anemia.

DIAGNOSIS

Anemia is typically diagnosed on a complete blood count. Apart from reporting the number of red blood cells and the hemoglobin level, the automatic counters also measure the size of the red blood cells by flow cytometry, which is an important tool in distinguishing between the causes of anemia.

Examination of a stained blood smear using a microscope can also be helpful, and is sometimes a necessity in regions of the world where automated analysis is less accessible. Reticulocyte counts, and the "kinetic" approach to anemia, have become more common than in the past in the large medical centers of the United States and some other wealthy nations; in part, because some automatic counters now have the capacity to include reticulocyte counts. This is a quantitative measure of the bone marrow's production of new red blood cells. The reticulocyte production index is a calculation of the ratio between the level of anemia and the extent to which the reticulocyte count has risen in response.

If the degree of anemia is significant, even a "normal" reticulocyte count actually may reflect an inadequate response.

In the morphological approach, anemia is classified by the size of red blood cells. This either done automatically or on microscopic examination of a peripheral blood smear. The size is reflected in the mean corpuscular volume (MCV). This scheme quickly exposes some of the most common causes of anemia. For instance, a microcytic anemia (smaller than usual red blood cells) is often the result of iron deficiency.

In clinical workup, the MCV will be one of the first pieces of information available; so even among clinicians who consider the "kinetic" approach more useful philosophically, morphology will remain an important element of classification and diagnosis.

IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

This is the most common type of anemia overall and it has many causes. Iron is an essential part of hemoglobin, and low iron levels result in decreased incorporation of hemoglobin into red blood cells. It is due to insufficient dietary intake or absorption of iron to meet the body's needs. Infants, toddlers, and pregnant women have higher-than-average needs. Increased iron intake is also needed to offset blood losses due to digestive tract issues, frequent blood donations, or heavy menstrual periods.

In the United States, the most common cause of iron deficiency is bleeding or blood loss, usually from the gastrointestinal tract. Fecal occult blood testing, upper endoscopy, and lower endoscopy should be performed to identify bleeding lesions. In older men and women, the chances are higher that bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract could be due to colon polyp or colorectal cancer.

Worldwide, the most common cause of iron deficiency anemia is parasitic infestation (hookworm, amebiasis, schistosomiasis, and whipworm).