This is “Monetary Policy Tools”, chapter 16 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (238 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

Chapter 16 Monetary Policy Tools

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- List and assess the strengths and weaknesses of the three primary monetary policy tools that central banks have at their disposal.

- Describe the federal funds market and explain its importance.

- Explain how the Fed influences the equilibrium fed funds rate to move toward its target rate.

- Explain the purpose of the Fed’s discount window and other lending facilities.

- Compare and contrast the monetary policy tools of central banks worldwide to those of the Fed.

16.1 The Federal Funds Market and Reserves

Learning Objectives

- What three monetary policy tools do central banks have at their disposal?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of each? What is the federal funds market and why is it important?

Central banks have three primary tools for influencing the money supply: the reserve requirement, discount loans, and open market operations. The first, as we saw in Chapter 14 "The Money Supply Process" and Chapter 15 "The Money Supply and the Money Multiplier", works through the money multiplier, constraining multiple deposit expansion the larger it becomes. Central banks today rarely use it because most banks work around reserve requirements. The second and third tools influence the monetary base (MB = C + R). Discount loans depend on banks (or nonbank borrowers, where applicable) first borrowing from, then repaying loans to, the central bank, which therefore does not have precise control over MB. Open market operations (OMO) are generally preferred as a policy tool because the central bank can easily expand or contract MB to a precise level. Using OMO, central banks can also reverse mistakes quickly.

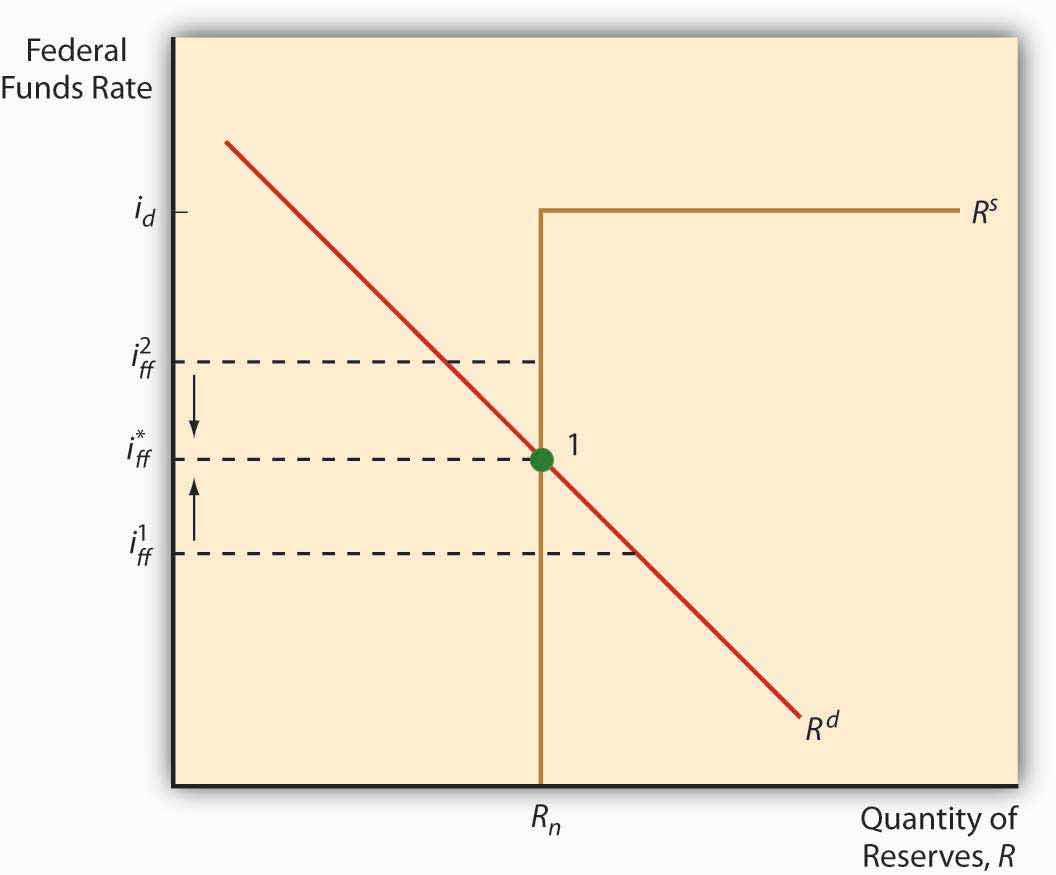

In the United States, under typical conditions, the Fed conducts monetary policy primarily through the federal funds (fed funds) market, an overnight market where banks that need reserves can borrow them from banks that hold reserves they don’t need. Banks can also borrow their reserves directly from the Fed, but, except during crises, most prefer not to because the Fed’s discount rate is generally higher than the federal funds rate. Also, borrowing too much, too often from the Fed can induce increased regulatory scrutiny. So usually banks get their overnight funds from the fed funds market, which, as Figure 16.1 "Equilibrium in the fed funds market" shows, pretty much works like any other market.

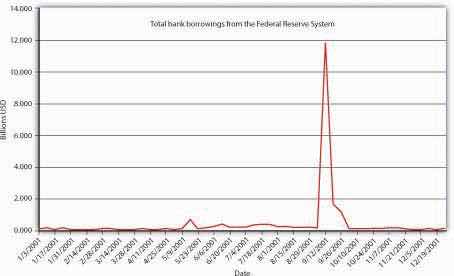

Figure 16.1 Equilibrium in the fed funds market

The downward slope of the demand curve for reserves is easily explained. Like anything else, as the price of reserves (in this case, the interest rate paid for them) increases, the quantity demanded decreases. As reserves get cheaper, banks will want more of them because the opportunity cost of that added protection, of that added liquidity, is lower. But what is the deal with that upside down L-looking reserve supply curve? Note that the curve takes a hard right (becomes infinitely elastic) at the discount rate. That’s because, if the federal funds rate ever exceeded the discount rate, banks’ thirst for Fed discount loans would be unquenchable because a clear arbitrage opportunity would exist: borrow at the discount rate and relend at the higher market rate. Below that point, the reserve supply curve is vertical (perfectly inelastic) at whatever quantity the Fed wants to supply via open market operations.

The intersection of the supply and demand curves is the equilibrium or market rate, the actual federal funds rate, ff*. When the Fed makes open market purchases, the supply of reserves shifts right, lowering ff* (ceteris paribus). When it sells, it moves the reserve supply curve left, increasing ff*, all else constant. The discount rate sets an upper limit to ff* because no bank would borrow reserves at a higher rate in the federal funds market than it could borrow directly from the Fed.

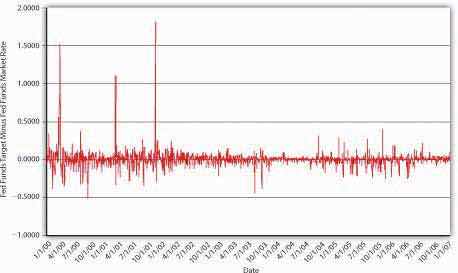

Figure 16.2 Fed funds targeting, 2000–2007

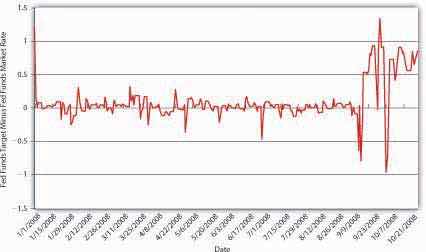

Figure 16.3 Fed funds targeting, 2008

Theoretically, the Fed could also directly affect the demand for reserves by changing the reserve requirement. If it increased (decreased) rr, demand for reserves would shift up (down), increasing (decreasing) ff*. As noted above, however, banks these days can so easily sidestep required reserves that the Fed’s ability to influence the demand for reserves is extremely limited. Demand for reserves can also shift right or left due to bank liquidity management activities, increasing (decreasing) as expectations of net deposit outflows increase (decrease). The Fed tries to anticipate such shifts and generally has done a good job of it. Although there have been days when ff* differed from the target by several percentage points (several hundred basis points), between 1982 and 2007, the fed funds target was, on average, only .0340 of a percent lower than ff*. Between 2000 and the subprime mortgage uproar in the summer of 2007, the Fed did an even better job of moving ff* to its target, as Figure 16.2 "Fed funds targeting, 2000–2007" shows. During the crises of 2007 and 2008, however, the Fed often missed its target by a long way, as shown in Figure 16.3 "Fed funds targeting, 2008".

Stop and Think Box

In Chapter 13 "Central Bank Form and Function", you learned that America’s first central banks, the BUS and SBUS, controlled commercial bank reserve levels by varying the speed and intensity by which it redeemed convertible bank liabilities (notes and deposits) for reserves (gold and silver). Can you model that system?

Kudos if you can! I’d plot quantity of reserves along the horizontal axis and interest rate along the vertical axis. The reserve supply curve was probably highly but not perfectly inelastic and the reserve demand curve sloped downward, of course. When the BUS or SBUS wanted to tighten monetary policy, it would return commercial bank monetary liabilities in a great rush, pushing the reserve demand curve to the right, thereby raising the interest rate. When it wanted to soften, it would dawdle before redeeming notes for gold and so forth, allowing the demand for reserves to move left, thereby decreasing the interest rate.

Key Takeaways

- Central banks can influence the money multiplier (simple, m1, m2, etc.) via reserve requirements.

- That tool is somewhat limited these days given the introduction of sweep accounts and other reserve requirement loopholes.

- Central banks can also influence MB via loans to banks and open market operations.

- For day-to-day policy implementation, open market operations are preferable because they are more precise and immediate and almost completely under the control of the central bank, which means it can reverse mistakes quickly.

- Discount loans depend on banks borrowing and repaying loans, so the central bank has less control over MB if it relies on loans alone.

- Discount loans are therefore used now primarily to set a ceiling on the overnight interbank rate and to provide liquidity during crises.

- The federal funds market is the name of the overnight interbank lending market, basically the market where banks borrow and lend bank reserves, in the United States.

- It is important because the Fed uses open market operations (OMO) to move the equilibrium rate ff* toward the target established by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

16.2 Open Market Operations and the Discount Window

Learning Objectives

- How does the Fed influence the equilibrium fed funds rate to move toward its target rate?

- What purpose does the Fed’s discount window now serve?

In practical terms, the Fed engages in two types of OMO, dynamic and defensive. As those names imply, it uses dynamic OMO to change the level of the MB, and defensive OMO to offset movements in other factors affecting MB, with an eye toward maintaining the federal funds target rate determined by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) at its most recent meeting.

As noted in Chapter 13 "Central Bank Form and Function", the responsibility for actual buying and selling government bonds devolves upon the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). Each trading day, FRBNY staff members look at the level of reserves, the fed funds target, the actual market fed funds rate, expectations regarding float, and Treasury activities. They also garner information about Treasury market conditions through conversations with so-called primary dealers, specialized firms and banks that make a marketBuying securities from all comers at a bid price and reselling them to all comers at a slightly higher ask price. in Treasuries. With the input and consent of the Monetary Affairs Division of the Board of Governors, the FRBNY determines how much to buy or sell and places the appropriate order on the Trading Room Automated Processing System (TRAPS) computer system that links all the primary dealers. The FRBNY then selects the best offers up to the amount it wants to buy or sell. It enters into two types of trades, so-called outright ones, where the bonds permanently join or leave the Fed’s balance sheet, and temporary ones, called repos and reverse repos. In a repo (aka a repurchase agreement), the Fed purchases government bonds with the guarantee that the sellers will repurchase them from the Fed, generally one to fifteen days hence. In a reverse repo (aka a matched sale-purchase transaction), the Fed sells securities and the buyer agrees to sell them to the Fed again in the near future. The availability of such self-reversing contracts and the liquidity of the government bond market render open market operations a precise tool for implementing the Fed’s monetary policy.

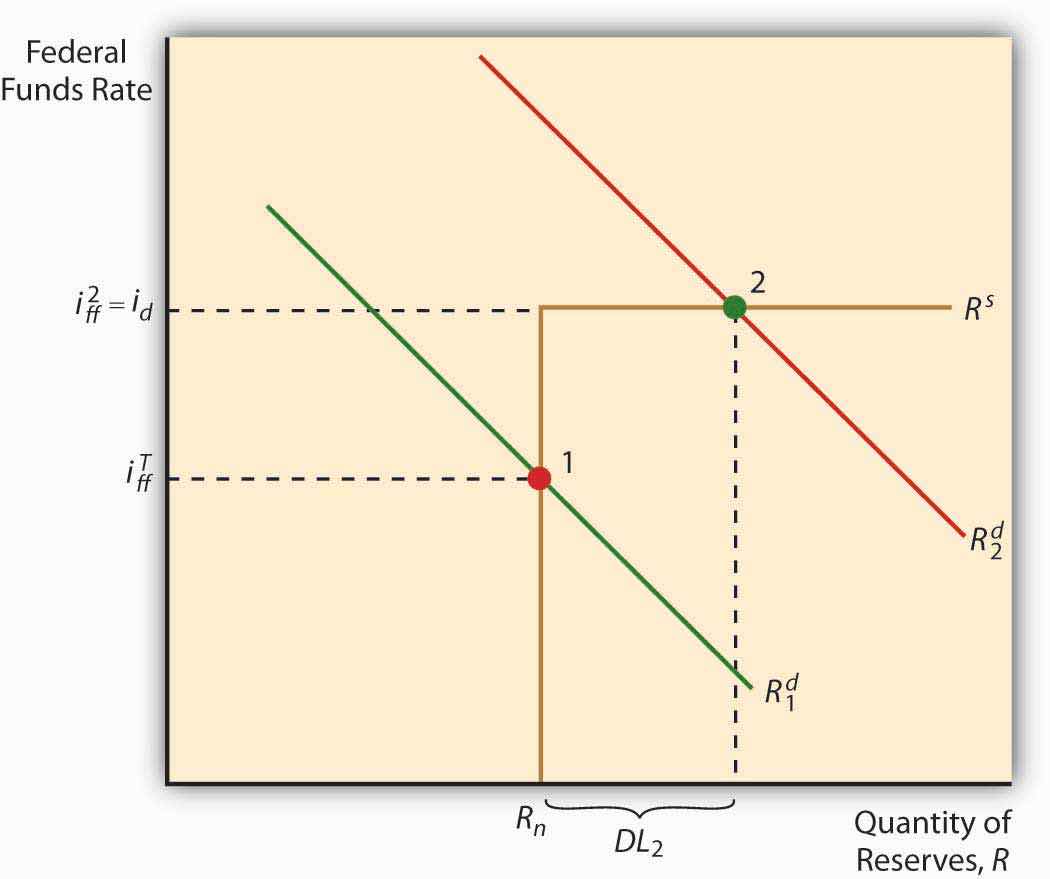

The so-called discount window, where banks come to borrow reserves from the Federal district banks, is today primarily a backup facility used during crises, when the federal funds market might not function effectively. As noted above, the discount rate puts an effective cap on ff* by providing banks with an alternative source of reserves (see Figure 16.4 "The discount window sets an upper bound on overnight interest rates"). Note that no matter how far the reserve demand curve shifts to the right, once it reaches the discount rate, it merely slides along it.

Figure 16.4 The discount window sets an upper bound on overnight interest rates

As lender of last resort, the Fed has a responsibility to ensure that borrowers can obtain as much as they want to borrow provided they can post what in normal times would be considered good collateral security. To ensure that banks do not rely too heavily on the discount window, the discount rate is usually set a full percentage point above ff*, a “penalty” of 100 basis points. (This policy is usually known as Bagehot’s Law, but the insight actually originated with Alexander Hamilton, America’s first Treasury secretary, so we call it Hamilton’s Law.) On several occasions (including the 1984 failure of Continental Illinois, a large commercial bank; the stock market crash of 1987; and the subprime mortgage debacle of 2007), the discount window added the liquidity (reserves) and confidence necessary to stave off more serious disruptions to the economy, like those described in Chapter 12 "The Financial Crisis of 2007–2008" and Chapter 23 "Aggregate Supply and Demand, the Growth Diamond, and Financial Shocks".

During the financial crisis of 2008, during which many credit markets stopped functioning properly, the Federal Reserve invoked its emergency powers to create additional lending powers and programs, including the following:http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/

- Term Auction Facility (TAF), a “credit facility” that allows depository institutions to bid for short term funds at a rate established by auction.

- Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), which provides overnight loans to primary dealers at the discount rate.

- Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF), which also helps primary dealers by exchanging Treasuries for riskier collateral for twenty-eight-day periods.

- Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Liquidity Facility, which helps money market mutual funds to meet redemptions without having to sell their assets into distressed markets.

- Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), which allows the FRBNY, through a special-purpose vehicleAn organizational entity created to perform a specific, or special, task. (SPV), to purchase commercial paper (short-term bonds) issued by nonfinancial corporations.

- Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF), which is another lending program designed to help the money markets (markets for short-term bonds) return to normal.

Presumably, most or all of these programs will phase out as credit conditions return to normal. The Bank of England and other central banks have implemented similar programs.“Credit Markets: A Lifeline for Banks. The Bank of England’s Bold Initiative Should Calm Frayed Financial Nerves,” The Economist, April 26, 2008, 74–75.

Stop and Think Box

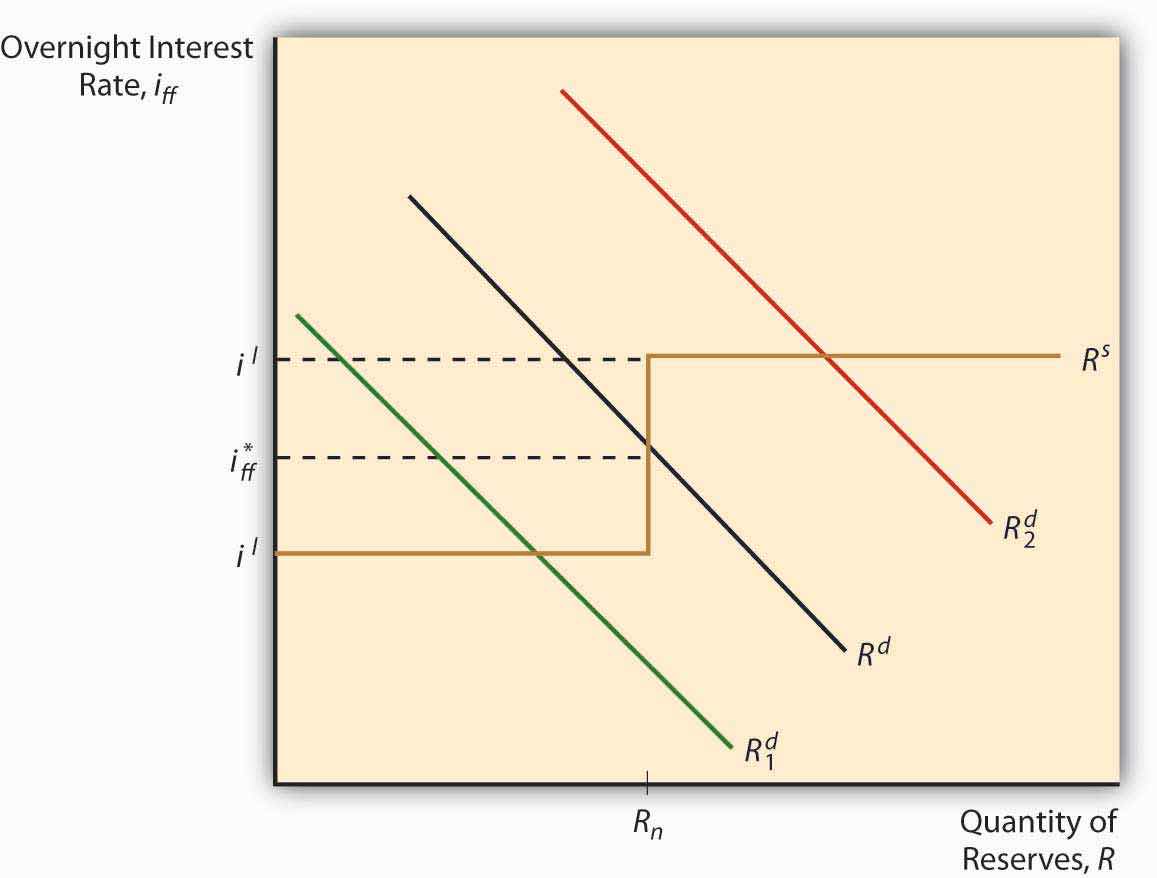

What in Sam Hill happened in Figure 16.5 "Total bank borrowings from the Federal Reserve System, 2001"? (Hint: The dates are important.)

Figure 16.5 Total bank borrowings from the Federal Reserve System, 2001

Terrorists attacked New York City and Washington, DC, with hijacked airplanes, shutting down the nation and parts of the financial system for the better part of a week. Some primary dealers were destroyed in the attacks, which also brought on widespread fears of bankruptcies and bank runs. Banks beefed up reserves by selling bonds to the Fed and by borrowing from its discount window. (Excess reserves jumped from a long-term average of around $1 billion to $19 billion.) This is an excellent example of the discount window providing lender-of-last-resort services to the economy.

The discount window is also used to provide moderately shaky banks a longer-term source of credit at an even higher penalty rate .5 percentage (50 basis) points above the regular discount rate. Finally, the Fed will also lend to a small number of banks in vacation and agricultural areas that experience large deposit fluctuations over the course of a year. Increasingly, however, such banks are becoming part of larger banks with more stable deposit profiles, or they handle their liquidity management using the market for negotiable certificates of deposit NCDs or other market borrowings.

Key Takeaways

- The Fed can move the equilibrium fed funds rate toward its target by changing the demand for reserves by changing the required reserve ratio. However, it rarely does so anymore.

- It can also shift the supply curve to the right (add reserves to the system) by buying assets (almost always Treasury bonds) or shift it to the left (remove reserves from the system) by selling assets.

- The discount window caps ff* because if ff* were to rise above the Fed’s discount rate, banks would borrow reserves from the Fed (technically its district banks) instead of borrowing them from other banks in the fed funds market.

- Because the Fed typically sets the discount rate a full percentage point (100 basis) points above its feds fund target, ff* rises above the discount rate only in a crisis, as in the aftermath of the 1987 stock market crash and the 2007 subprime mortgage debacle.

16.3 The Monetary Policy Tools of Other Central Banks

Learning Objective

- In what ways are the monetary policy tools of central banks worldwide similar to those of the Fed? In what ways do they differ?

The European Central Bank (ECB) also uses open market operations to move the market for overnight interbank lending toward its target. It too uses repos and reverse repos for reversible, defensive OMO and outright purchases for permanent additions to MB. Unlike the Fed, however, the ECB spreads the love around, conducting OMO in multiple cities throughout the European Union. The ECB’s national central banks (NCBs,) like the Fed’s district banks, also lend to banks at a so-called marginal lending rate, which is generally set 100 basis points above the overnight cash rate. The ECB pays interest on reserves, a practice the Fed took up only recently.

Canada, New Zealand, and Australia do likewise and have eliminated reserve requirements, relying instead on what is called the channel, or corridor, system. As Figure 16.6 "Paying interest on reserves puts a floor under the overnight interest rate" depicts, the supply curve in the corridor system looks like a backward Z. The vertical part of the supply curve represents the area in which the central bank engages in OMO to influence the market rate, i*, to meet its target rate, it. The top horizontal part of the supply curve, il for the Lombard rate, is the functional equivalent of the discount rate in the American system. The ECB and other central banks using this system, like the Fed, will lend at this rate whatever amount banks with good collateral desire to borrow. Under normal circumstances, that quantity is nil because it (and i*) will be 25, 50, or more basis points lower, depending on the country. The innovation is the lower horizontal part of the supply curve, ir, or the rate at which the central bank pays banks to hold reserves. That sets a floor on i* because no bank would lend in the overnight market if it could earn a higher return by depositing its excess funds with the central bank. Using the corridor system, a central bank can keep the overnight rate within the bands set by il and ir and use OMO to keep i* near it.

Figure 16.6 Paying interest on reserves puts a floor under the overnight interest rate

In response to the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed began to pay interest rates on reserves and will likely continue to do so because it appears to have become central bank best practicePolicies generally considered to be state of the art in a given industry, to be something that nonconforming organizations ought to emulate..

Key Takeaways

- Most central banks now use OMO instead of discount loans or reserve requirement adjustments for conducting day-to-day monetary policy.

- Some central banks, including those of the euro zone and the British Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) have developed an ingenious new method called the channel or corridor system.

- Under that system, the central bank conducts OMO to get the overnight interbank lending rate near the central bank’s target, as the Fed does in the United States.

- That market rate is capped at both ends, however: on the upper end by the discount (aka Lombard) rate, and at the lower end by the reserve rate, the interest rate the central bank pays to banks for holding reserves.

- The market overnight rate can never dip below that rate because banks would simply invest their extra funds in the central bank rather than lend them to other banks at a lower rate.

- During the financial crisis of 2008, the Fed adopted the corridor system by paying interest on reserves.

16.4 Suggested Reading

Hetzel, Robert L. The Monetary Policy of the Federal Reserve: A History. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Mishkin, Frederic S. Monetary Policy Strategy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.