This is “The Money Supply Process”, chapter 14 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (205 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

Chapter 14 The Money Supply Process

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Describe who determines the money supply.

- Explain how the central bank’s balance sheet differs from the balance sheets of commercial banks and other depository institutions.

- Define the monetary base and explain its importance.

- Define open market operations and explain how they affect the monetary base.

- Describe the multiple deposit creation process.

- Define the simple deposit multiplier and explain its information content.

- List and explain the two major limitations or assumptions of the simple deposit multiplier.

14.1 The Central Bank’s Balance Sheet

Learning Objectives

- Who determines the money supply?

- How does the central bank’s balance sheet differ from the balance sheets of other banks?

- What is the monetary base?

Ultimately the money supply is determined by the interaction of four groups: commercial banks and other depositories, depositors, borrowers, and the central bank. Like any bank, the central bank’s balance sheet is composed of assets and liabilities. Its assets are similar to those of common banks and include government securitiesStudents sometimes become confused about this because they think the central bank is the government. At most, it is part of the government, and not the part that issues the bonds. Sometimes, as in the case of the BUS and SBUS, it is not part of the government at all. and discount loans. The former provide the central bank with income and a liquid asset that it can easily and cheaply buy and sell to alter its balance sheet. The latter are generally loans made to commercial banks. So far, so good. The central bank’s liabilities, however, differ fundamentally from those of common banks. Its most important liabilities are currency in circulation and reserves.

Yes, currency and reserves. You may recall from Chapter 9 "Bank Management" that those are the assets of commercial banks. In fact, for everyone but the central bank, the central bank’s notes, Federal Reserve notes (FRN) in the United States, are assets, things owned. But for the central bank, its notes are things owed (liabilities), just like your promissory note (IOU) would be your liability, but it would be an asset for the note’s holder or owner. Similarly, commercial banks own their deposits in the Fed (reserves), which the Fed, of course, owes to the commercial banks. So reserves are commercial bank assets but central bank liabilities.

Currency in circulation (C) and reserves (R) compose the monetary baseThe most basic, powerful types of money in a given monetary system, that is, gold and silver under the gold standard, FRN, and reserves (Federal Reserve deposits) today. (MB, aka high-powered money), the most basic building blocks of the money supply. Basically, MB = C + R, an equation you’ll want to internalize. In the United States, C includes FRN and coins issued by the U.S. Treasury. We can ignore the latter because it is a relatively small percentage of the MB, and the Treasury cannot legally manage the volume of coinage in circulation in an active fashion, but rather only meets the demand for each denomination: .01, .05, .10, .25, .50, and 1.00 coins. (The Fed also supplies the $1.00 unit, and for some reason Americans prefer $1 notes to coins. In most countries, coins fill demand for the single currency unit denomination.) C includes only FRN and coins in the hands of nonbanks. Any FRN in banks is called vault cash and is included in R, which also includes bank deposits with the Fed. Reserves are of two types: those required or mandated by the central bank (RR), and any additional or excess reserves (ER) that banks wish to hold. The latter are usually small, but they can grow substantially during panics like that of September–October 2008.

Central banks, of course, are highly profitable institutions because their assets earn interest but their liabilities are costless, or nearly so. Therefore, they have no gap problems, and liquidity management is a snap because they can always print more notes or create more reserves. Central banks anachronistically own prodigious quantities of gold, but some have begun to sell off their holdings because they no longer convert their notes into gold or anything else for that matter.http://news.goldseek.com/GoldSeek/1177619058.php Gold is no longer part of the MB but is rather just a commodity with an unusually high value-to-weight ratio.

Key Takeaways

- The central bank, depository institutions of every stripe, borrowers, and depositors all help to determine the money supply.

- The central bank helps to determine the money supply by controlling the monetary base (MB), aka high-powered money or its monetary liabilities.

- The central bank’s balance sheet differs from those of other banks because its monetary liabilities, currency in circulation (C) and reserves (R), are everyone else’s assets.

- The monetary base or MB = C + R, where C = currency in circulation (not in the central bank or any bank); R = reserves = bank vault cash and deposits with the central bank.

- MB is important because an increase (decrease) in it will increase (decrease) the money supply (M1—currency plus checkable deposits, M2—M1 plus time deposits and retail money market deposit accounts, etc.) by some multiple (hence the “high-powered” nickname).

14.2 Open Market Operations

Learning Objective

- What are open market operationsThe purchase or sale of assets by a central bank in order to adjust the money supply. See monetary base. and how do they affect the monetary base?

We are now ready to understand how the central bank influences the money supply (MS) with the aid of the T-accounts we first encountered in Chapter 9 "Bank Management". Central banks like the Fed influence the MS via the MB. They control their monetary liabilities, MB, by buying and selling securities, a process called open market operations. If a central bank wants to increase the MB, it need only buy a security. (Any asset will do, but securities, especially government bonds, are generally best because there is little default risk, liquidity is high, and they pay interest.) If a central bank bought a $10,000 bond from a bank, the following would occur:

| Banking System | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities −$10,000 | |

| Reserves +$10,000 | |

The banking system would lose $10,000 worth of securities but gain $10,000 of reserves (probably a credit in its account with the central bank but, as noted above, FRN or other forms of cash also count as reserves).

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities +$10,000 | Reserves +$10,000 |

The central bank would gain $10,000 of securities essentially by creating $10,000 of reserves. Notice that the item transferred, securities, has opposite signs, negative for the banking system and positive for the central bank. That makes good sense if you think about it because one party is selling (giving up) and the other is buying (receiving). Note also that the central bank’s liability has the same sign as the banking system’s asset. That too makes sense because, as noted above, the central bank’s liabilities are everyone else’s assets. So if the central bank’s liabilities increase or decrease, everyone else’s assets should do likewise.

If the central bank happens to buy a bond from the public (any nonbank), and that entity deposits the proceeds in its bank, precisely the same outcome would occur, though via a slightly more circuitous route:

| Some Dude | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities −$10,000 | |

| Checkable deposits +$10,000 | |

| Banking System | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Reserves +$10,000 | Checkable deposits +$10,000 |

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities +$10,000 | Reserves +$10,000 |

If the nonbank seller of the security keeps the proceeds as cash (FRN), however, the outcome is slightly different:

| Some Dude | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities −$10,000 | |

| Currency +$10,000 | |

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities +$10,000 | Currency in circulation +$10,000 |

Note that in either case, however, the MB increases by the amount of the purchase because either C or R increases by the amount of the purchase. Keep in mind that currency in circulation means cash (like FRN) no longer in the central bank. An IOU in the hands of its maker is no liability; cash in the hands of its issuer is not a liability. So although the money existed physically before Some Dude sold his bond, it did not exist economically as money until it left its papa (mama?), the central bank. If the transaction were reversed and Some Dude bought a bond from the central bank with currency, the notes he paid would cease to be money, and currency in circulation would decrease by $10,000.

In fact, whenever the central bank sells an asset, the exact opposite of the above T-accounts occurs: the MB shrinks because C (and/or R) decreases along with the central bank’s securities holdings, and banks or the nonbank public own more securities but less C or R.

The nonbank public can influence the relative share of C and R but not the MB. Say that you had $55.50 in your bank account but wanted $30 in cash to take your significant other to the carnival. Your T-account would look like the following because you turned $30 of deposits into $30 of FRN:

| Your T-Account | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Checkable deposits −$30.00 | |

| Currency +$30.00 | |

Your bank’s T-account would look like the following because it lost $30 of deposits and $30 of reserves, the $30 you walked off with:

| Your Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Reserves −$30.00 | Checkable deposits −$30.00 |

The central bank’s T-account would look like the following because the nonbank public (you!) would hold $30 and your bank’s reserves would decrease accordingly (as noted above):

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Currency in circulation $30.00 | |

| Reserves −$30.00 | |

The central bank can also control the monetary base by making loans to banks and receiving their loan repayments. A loan increases the MB and a repayment decreases it. A $1 million loan and repayment a week later looks like this:

| Central Bank | ||

|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Date |

| Loans +$1,000,000 | Reserves +$1,000,000 | January 1, 2010 |

| Loans −$1,000,000 | Reserves −$1,000,000 | January 8, 2010 |

| Banking System | ||

|---|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities | Date |

| Reserves +$1,000,000 | Borrowings +$1,000,000 | January 1, 2010 |

| Reserves −$1,000,000 | Borrowings −$1,000,000 | January 8, 2010 |

Take time now to practice deciphering the effects of open market operations and central bank loans and repayments via T-accounts in Exercise 1. You’ll be glad you did.

Exercises

Use T-accounts to describe what happens in the following instances:

- The Bank of Japan sells ¥10 billion of securities to banks.

- The Bank of England buys £97 million of securities from banks.

- Banks borrow €897 million from the ECB.

- Banks repay $C80 million of loans to the Bank of Canada.

- The Fed buys $75 billion of securities from the nonbank public, which deposits $70 billion and keeps $5 billion in cash.

Key Takeaways

- Open market operations occur whenever a central bank buys or sells assets, usually government bonds.

- By purchasing bonds (or anything else for that matter), the central bank increases the monetary base and hence, by some multiple, the money supply. (Picture the central bank giving up some money to acquire the bond, thereby putting FRN or reserves into circulation.)

- By selling bonds, the central bank decreases the monetary base and hence the money supply by some multiple. (Picture the central bank giving up a bond and receiving money for it, removing FRN or reserves from circulation.)

- Similarly, the MB and MS increase whenever the Fed makes a loan, and they decrease whenever a borrower repays the Fed.

14.3 A Simple Model of Multiple Deposit Creation

Learning Objectives

- What is the multiple deposit creation process?

- What is the money multiplier?

- What are the major limitations of the simple deposit multiplier?

As shown above, the central bank pretty much controls the size of the monetary base. (The check clearing process and the government’s banking activities can cause some short-term flutter, but generally the central bank can anticipate such fluctuations and respond accordingly.) That does not mean, however, that the central bank controls the money supply, which, if you recall from Chapter 3 "Money", consists of more than just MB. (M1, for example, also includes checkable deposits.) The reason is that each $1 (or €1, etc.) of additional MB creates some multiple > 1 of new deposits in a process called multiple deposit creation.

Suppose the central bank buys $1 million of securities from Some Bank. We know that the following will occur:

| Some Bank | |

|---|---|

| Liabilities | |

| Securities −$1 million | |

| Reserves +$1 million | |

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities +$1 million | Reserves +$1 million |

Some Bank suddenly has $1 million in excess reserves. (Its deposits are unchanged, but it has $1 million more in cash.) What will the bank do? Likely what banks do best: make loans. So its T-account will be the following:

| Some Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Loans +$1 million | Deposits +$1 million |

Recall from Chapter 9 "Bank Management" that deposits are created in the process of making the loan. The bank has effectively increased M1 by $1 million. The borrower will not leave the proceeds of the loan in the bank for long but instead will use it, within the guidelines set by the loan’s covenants, to make payments. As the deposits flow out of Some Bank, its excess reserves decline until finally Some Bank has essentially swapped securities for loans:

| Some Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Securities −$1 million | |

| Loans +$1 million | |

But now there is another $1 million of checkable deposits out there and they rarely rest. Suppose, for simplicity’s sake, they all end up at Another Bank. Its T-account would be the following:

| Another Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets Bank | Liabilities |

| Reserves +$1 million | Checkable deposits +$1 million |

If the required reserve ratio (rr) is 10 percent, Another Bank can, and likely will, use those deposits to fund a loan, making its T-account:

| Another Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Reserves +$.1 million | Checkable Deposits +$1 million |

| Loans +$.9 million | |

That loan will also eventually be paid out to others and deposited into other banks, which in turn will lend 90 percent of them (1 − rr) to other borrowers. Even if a bank decides to invest in securities instead of loans, as long as it buys the bonds from anyone but the central bank, the multiple deposit creation expansion will continue, as in Figure 14.1 "Multiple deposit creation, with an increase in reserves of $1 million, if rr = .10".

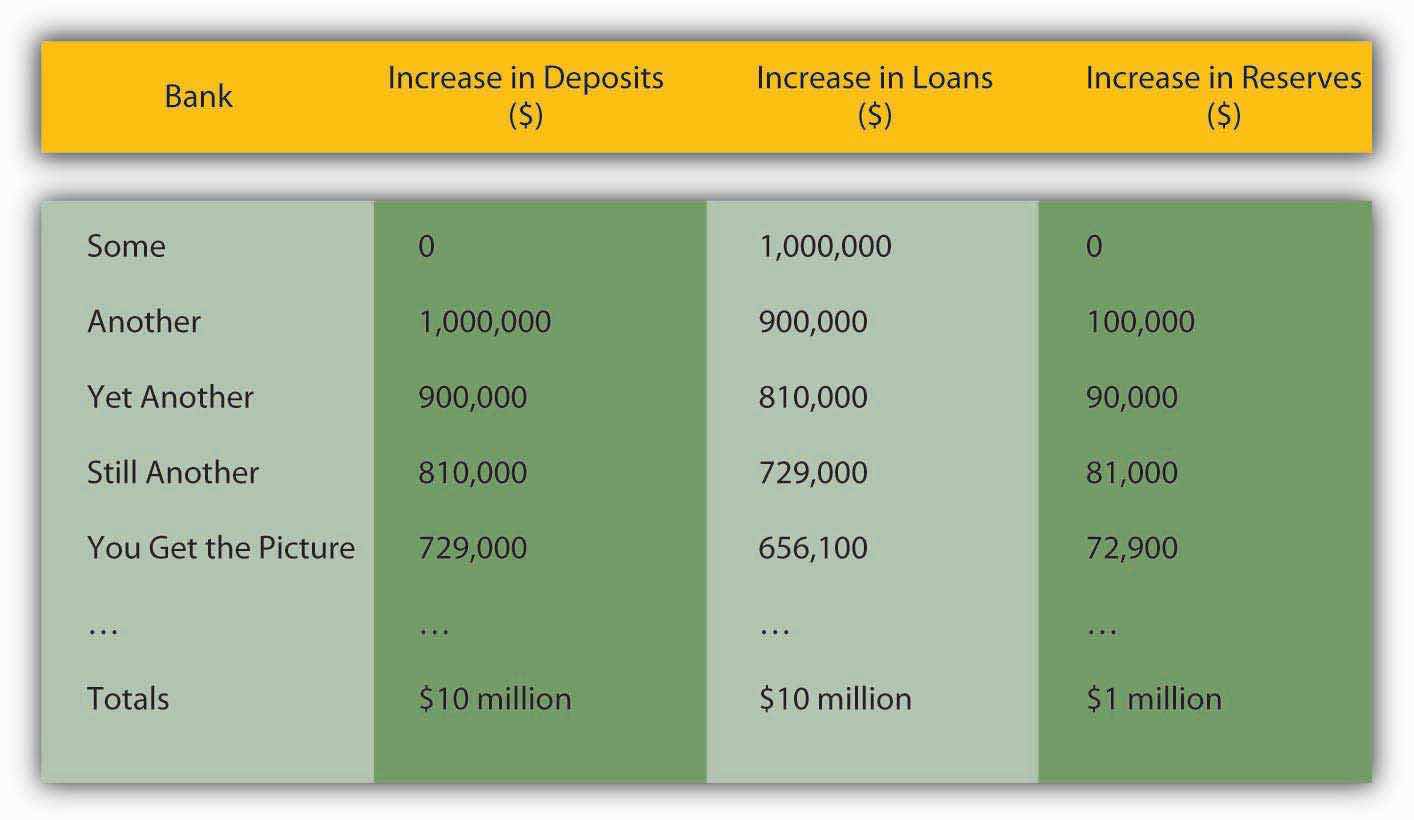

Figure 14.1 Multiple deposit creation, with an increase in reserves of $1 million, if rr = .10

Notice that the increase in deposits is the same as the increase in loans from the previous bank. The increase in reserves is the increase in deposits times the required reserve ratio of .10, and the increase in loans is the increase in deposits times the remainder, .90. Rather than working through this rather clunky process every time, you can calculate the effects of increasing reserves with the so-called simple deposit multiplier formula:

where:

∆D = change in deposits

∆R = change in reserves

Rr = required reserve ratio

1/.1 × 1 million = 10 million, just as in Figure 14.1 "Multiple deposit creation, with an increase in reserves of $1 million, if rr = .10"Practice calculating the simple deposit multiplier in Exercise 2.

Exercise

-

Use the simple deposit multiplier ∆D = (1/rr) × ∆R to calculate the change in deposits given the following conditions:

Required Reserve Ratio Change in Reserves Answer: Change in Deposits .1 10 100 .5 10 20 1 10 10 .1 −10 −100 .1 100 1,000 0 43.5 ERROR—cannot divide by 0

Stop and Think Box

Suppose the Federal Reserve wants to increase the amount of checkable deposits by $1,000,000 by conducting open market operations. Using the simple model of multiple deposit creation, determine what value of securities the Fed should purchase, assuming a required reserve ratio of 5 percent. What two major assumptions does the simple model of multiple deposit creation make? Show the appropriate equation and work.

The Fed should purchase $50,000 worth of securities. The simple model of multiple deposit creation is ∆D = (1/rr) ×∆R, which of course is the same as ∆R = ∆D/(1/rr). So for this problem 1,000,000/(1/.05) = $50,000 worth of securities should be purchased. This model assumes that money is not held as cash and that banks do not hold excess reserves.

Pretty easy, eh? Too bad the simple deposit multiplier isn’t very accurate. It provides an upper bound to the deposit creation process. The model simply isn’t very realistic. Sometimes banks hold excess reserves, and people sometimes prefer to hold cash instead of deposits, thereby stopping the multiple deposit creation process cold. That is why, at the beginning of the chapter, we said that depositors, borrowers, and banks were also important players in the money supply determination process. In the next chapter, we’ll take their decisions into account.

Key Takeaways

- The multiple deposit creation process works like this: say that the central bank buys $100 of securities from Bank 1, which lends the $100 in cash it receives to some borrower. Said borrower writes checks against the $100 in deposits created by the loan until all the money rests in Bank 2. Its deposits and reserves increased by $100, Bank 2 lends as much as it can, say (1 – rr = .9) or $90, to another borrower, who writes checks against it until it winds up in Bank 3, which also lends 90 percent of it. Bank 4 lends 90 percent of that, Bank 5 lends 90 percent of that, and so on, until a $100 initial increase in reserves has led to a $1,000 increase in deposits (and loans).

- The simple deposit multiplier is ∆D = (1/rr) × ∆R, where ∆D = change in deposits; ∆R = change in reserves; rr = required reserve ratio.

- The simple deposit multiplier assumes that banks hold no excess reserves and that the public holds no currency. We all know what happens when we assume or ass|u|me. These assumptions mean that the simple deposit multiplier overestimates the multiple deposit creation process, providing us with an upper-bound estimate.

14.4 Suggested Reading

Hummel, William. Money: What It Is, How It Works 2nd ed. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2006.

Mayes, David, and Jan Toporowski. Open Market Operations and Financial Markets. New York: Routledge, 2007.