Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The invasion of Belgium brought in its protector, Great Britain, who fought with the French against Germany and its ally Austria-Hungary along a long line of fortified positions that began a deadly new form of confrontation known as “trench warfare”.

The Western Front (1917)

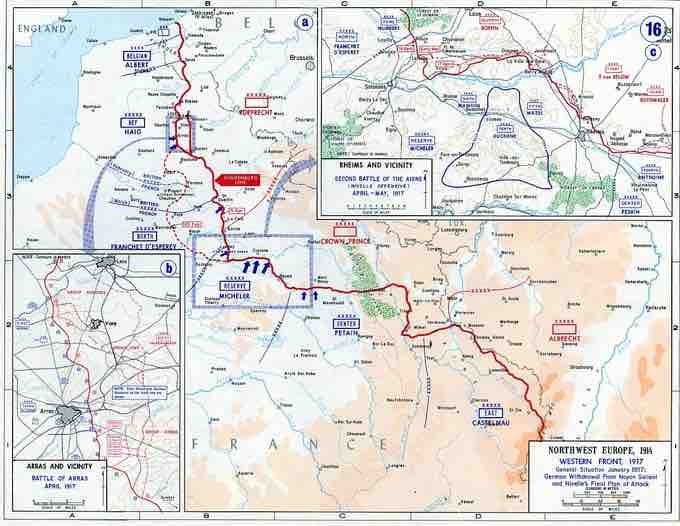

Map of the Western Front, 1917.

The Western Front Opens

The opening of the Western Front occurred at the beginning of the conflict in the summer of 1914 when, rather than attack France directly on their smaller shared border, Germany swept to the west through Luxembourg and Belgium and then turned south in order to enter France across its northern border. This was a modified version of a German invasion blueprint known as the Schlieffen Plan, named for Germany Army Chief of Staff Alfred von Schlieffen, who designed the strategy to quickly overwhelm the French Army.

In its original form, the Schlieffen Plan called for German forces along the French border to attack to the south in areas such as Strasbourg and then pull back in a feigned defeat, causing the French Army to surge south with reinforcement troops and leave the north weakened, thus allowing Germany to push down from the north and make a move to encircle the French forces. This was countered, however, when the new chief of staff, Helmuth von Moltke, diverted from the original plan and attacked in the south rather than fall back. Many historians assert this was due to Moltke’s indecision at the time of the French invasion, fearing a Russian attack in the east but also enticed by an unplanned chance of victory at Lorraine where he was meant to withdraw.

The initial invasion into France saw the Germans fight the Allies in the Battle of the Frontiers, a series of engagements in eastern France and southern Belgium, until they were nearing the outskirts of Paris. In a counter attack along the Marne River from September 5-12, 1917, which came to be known as the First Battle of the Marne, or the Miracle of the Marne, six French combat groups with the help of the British Expeditionary Force pushed the Germans northwest back toward their own border.

This began the so-called Race to the Sea, a series of battles in which the sides tried to outflank each other in the direction of France’s Atlantic coast. The race resulted in no clear advantage for either the Central Powers or the Allies, who faced off and dug in along a meandering series of fortified trenches that ran up through eastern and northern France into Belgium, a line of “trench warfare” that remained essentially unchanged for most of the war.

Critical and Crippling Battles

Between 1916 and 1917, there were several major offensives in the west. Yet a combination of entrenchments, machine gun nests, barbed wire, and artillery repeatedly inflicted severe casualties on both sides and prevented any significant advances. Among the most costly of these offensives were the Battle of Verdun, the Battle of the Somme, and the Battle of Passchendaele.

The Battle of Verdun began in February 1916. Over the summer and fall, the French slowly advanced and pushed the Germans back in one of the biggest battles of the war that became a symbol of French determination and sacrifice. Yet the price was high, both in numbers and morale. By the end of the Battle of Verdun in December, French casualties are estimated to have reached more than 337,000, including approximately 162,000 dead and missing; total German casualties have also been estimated around 337,000, with 100,000 of those dead or missing. The conditions were appalling, with the forests torn apart and the ground churned into a wasteland by artillery fire. Many troops suffered shell shock while others deserted. A French lieutenant, who was later killed, wrote in his diary on May 23, 1916: “Humanity is mad. It must be mad to do what it is doing. What a massacre! What scenes of horror and carnage. I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible. Men are mad!”

In July 1916, the British launched an attack around the Somme River in France. Despite massive troop losses, the British fought on through November in the face of German reinforcements, but even in the final phase produced limited gains with heavy loss of life. The Allies suffered about 620,000 casualties in the Battle of the Somme without realizing their goals.

In August 1916, new German leaders along the Western Front recognized that the battles of Verdun and the Somme had depleted the offensive capabilities of the German Army. They decided to take a defensive posture in the west and created a protective position called the Hindenburg Line.

In April 1917, French leaders ordered an offensive against the German trenches, promising it would be one to win the war. Dubbed the Nivelle Offensive, the attacked proceeded poorly and 100,000 French troops fell within a week. The attack continued and in May, 20,000 French soldiers deserted as morale decreased. Appeals to patriotism and duty, as well as mass arrests and trials resulting in firing squads, eventually convinced troops to return to defend their trenches, although the soldiers refused to participate in further offensive action.

Beginning on July 31 and continuing to November 10, 1917, an ongoing struggle around Ypres was renewed with the Battle of Passchendaele, officially known as the Third Battle of Ypres; the First Ypres took place from October-November 1914 and Second Ypres from April to May 1915. The final result of the third offensive, marked by British and Canadian forces taking the village of Passchendaele, was approximately five miles of territory gained with the loss of more than a half million men on both sides.

The tide of the German advance into France was finally, dramatically turned with the Second Battle of the Marne from July 15 to August 6, 1918. This would be the last German offensive of the war.

"At close grips"

Two United States soldiers run past the remains of two German soldiers toward a bunker. Trench warfare characterized the western front of World War I.

Arms Race

In an effort to break the deadlock, the Western Front saw the introduction of new military technology, such as chemical weapons. Airplanes had already been used in the war for scouting, and in 1915 a French pilot shot down an enemy plane. This started a back-and-forth arms race, as both sides developed improved aircraft capabilities. Tanks were also used extensively for the first time following the Somme, which led directly to new developments in infantry organization including small tactical units.

Final Phases and Armistice

On March 3, 1918, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed with Russia, releasing German and Austro-Hungarian troops to move from the Eastern Front to the fighting in the west. Yet a rapidly increasing American presence, eventually totaling 2.1 million U.S. soldiers on the Western Front, effectively countered the redeployed Germans. With its economy and society under great strain, Germany finally broke under the Allied series of attacks known as The Hundred Days Offensive beginning in August 1918. The combatants signed a ceasefire and all fighting on the Western Front ended on November 11, 1918, which became known as Armistice Day.