StartFragment

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were the United States troops, often called “Doughboys”, sent to fight in France alongside the British and French armies against Germany under the command of Major General John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing. The overall goal of the AEF was to reinforce the ongoing campaign against Germany by the French and British and bring the war to a victorious conclusion for the Allies.

Before the AEF

Between 1915 and 1917, before the beginning of major American involvement in the war, there were several offensives along the Western Front by the allied forces of Britain and France and the invading German forces intent on throwing each other backward until a sufficient amount of ground could be gained to claim victory.

Following the Race to the Sea, a series of battles aimed at flanking the enemy up to the Atlantic coast, and the decisive Battle of the Marne that stopped the German advance into France, the front line was established near the French and German border from the Swiss frontier to Belgium. The warring sides tried continuously to break the stalemate using a combination of massive artillery barrages, machine gun nests, snipers, poison gas, and aircraft attacks. The Battle of Verdun in 1916 produced an estimated 700,000 casualties from both sides, while the Battle of the Somme in that same year and the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 ended with a combined death total of more than 1.6 million men. These battles were marked by destructive attacks and counter-assaults by foot soldiers launched from opposing trenches.

Trench Warfare

Trench warfare epitomized the long, bloody conflict between the opposing armies on the Western Front, and has since become a term used when describing a futile battle marked by attrition – huge losses that achieve only negligible results.

The trenches were networks of defensive, fortified positions connected by sunken channels of varying lengths and quality. Some trenches were long, complicated systems that were dug deeply – from eight to 12 feet below the surface – and sturdily reinforced with wooden supports, shielding troops from artillery and small arms fire. Others were no more than dugouts that resembled large gutters along the frontlines. They were joined in zig-zagging or stepped patterns where no soldier could see down one trench more than about 10 meters (11 yards) and thus sectioned them off in order to prevent an entire trench from being captured if it was infiltrated at one point. The top lip of the trench was known as the parapet, and soldiers stood on steps below with hand-held periscopes – sometimes as simple as angled mirrors at the top and bottom of a stick – that enabled them to look out toward the enemy without being exposed.

French 87th Regiment Cote 34 Verdun, 1916

French soldiers of the 87th Regiment, 6th Division, at Côte 304 (Hill 304), northwest of Verdun, 1916.

The wet weather of the French countryside often turned the ground, already dug up badly by shelling, into fields of thick mud. Inside the trenches, the rain and muck could fill up the winding fortifications to the point that soldiers became trapped and some even drowned or suffocated under crumbling earthen walls. The armies faced off in their respective trenches with open areas of varying widths between them, called “no man’s land”, that were fully exposed to enemy fire and shelling and often crossed with long fences of barbed wire to slow the charges that soldiers were forced to make, resulting in enormous casualties regardless of their success.

The trenches of World War I produced far more horrors than quantifiable victories and the production of tanks, which were put into regular use in the latter part of the conflict, was a direct result of military leaders coming to the conclusion that trench warfare was an untenable strategy.

AEF Battles in France

During early 1918, four battle-ready U.S. divisions were deployed with French and British units to gain combat experience by defending relatively quiet sectors of their lines. After the first offensive action and AEF victory at the Battle of Cantigny on May 28 and another at Belleau Wood beginning June 6, Pershing worked to deploy a full field army. By June 1918, Americans arrived in the theater at a rate of 10,000 per day.

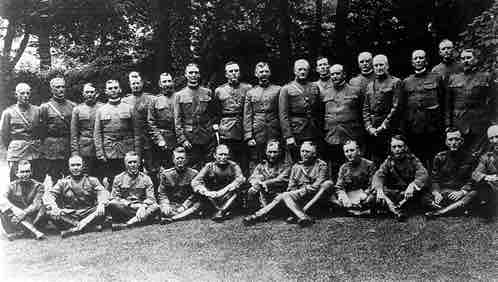

American Expeditionary Force

This photograph depicts officers in the American Expeditionary Forces. U.S. troops would become crucial to the Allied war by 1918.

The first AEF offensive action with British forces was conducted by 1,000 men serving with the Australian Imperial Forces during the Battle of Hamel on July 4, 1918. Combining artillery, armor, infantry, and air support, the battle was a blueprint for subsequent allied tank attacks. American Army and Marine Corps troops later played a key role in stopping the German thrust toward Paris during the Second Battle of the Marne in June 1918.

The first distinctly American offensive was the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, beginning September 12, 1918. Pershing commanded more than 500,000 men in the largest offensive operation ever undertaken by U.S. forces to date. This success was followed by the Meuse-Argonne offensive from September 26 to November 11, 1918, in which Pershing commanded more than 1 million American and French troops. In these two military operations, allied forces recovered more than 200 square miles of French territory from the Germans.

Overall the AEF sustained about 320,000 casualties and 204,000 wounded. The Fall 1918 influenza pandemic took the lives of more than 25,000 men, while another 360,000 became gravely ill. Other diseases were relatively well-controlled through compulsory vaccination.

By the time an armistice ended all fighting on November 11, 1918, the AEF had evolved into a modern, combat-tested army. Based on their success, European powers late in the war requested the aid of American units in Italy, as well as in Russia, where they were known as the American Expeditionary Force Siberia and the American Expeditionary Force North Russia.

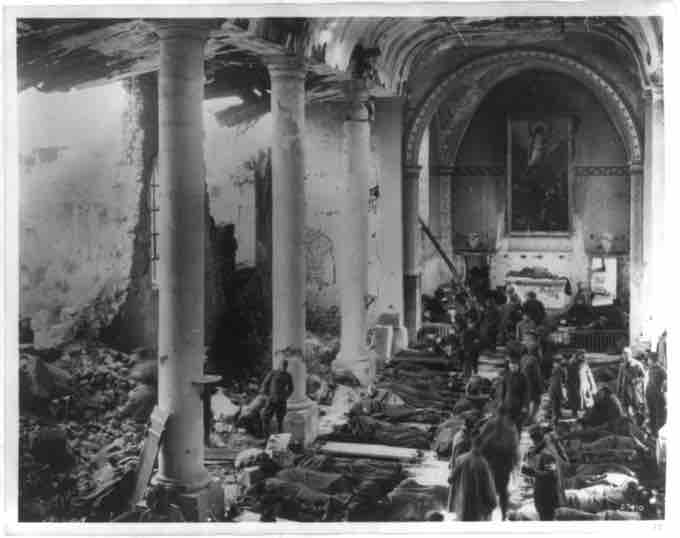

World War I Field Hospital

American Army field hospital inside ruins of a church (France 1918). The AEF sustained over 300,000 casualties.

African-Americans in the AEF

African-Americans were drafted on the same basis as whites and made up 13% of draftees. By the end of the war, more than 350,000 African-Americans served in AEF units on the Western Front, although they were assigned to segregated units commanded by white officers under a policy approved by President Wilson.

The French, whose front-line troops at times resisted combat duties to the point of mutiny, requested and received control of several regiments of black American combat troops. The French did not display the same levels of disdain based on skin color as the American Army and for many African-Americans it was a far more tolerable experience. The 370th, 371st, and 372nd Infantry Regiments served with distinction, while the 369th regiment became admiringly known as the Harlem Hellfighters.