The Selective Service Act, or Selective Draft Act, enacted May 18, 1917, authorized the federal government to raise a national army through conscription for American entry into World War I. It was envisioned in December 1916 and brought to President Woodrow Wilson shortly after America broke off relations with Germany in February 1917. Captain (later Brigadier General) Hugh Johnson wrote the act after the U.S. voted to support Wilson’s request for a declaration of war on April 4, 1917. The act was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the Selective Draft Law Cases in 1918, and then canceled with the end of fighting in November 1918.

Origins of the Draft

During the American Civil War, the Draft Act of 1863 was the first law making service in the federal military compulsory for men between the ages of 2o and 45. Yet for $300 a person who was not keen to fight could pay away the obligation, while draftees could also legally hire substitutes. These were expensive options only open to the wealthy and resulted in a disproportionately low number of rich men fighting in the war, which caused resentment among lower-class citizens and led to the July 1863 draft riots in New York City. When the draft was reinstituted in 1917, this previous conflict was directly addressed by outlawing the practice of draft buyouts or hiring surrogates.

At the outset of World War I in 1914, the U.S. Army was small compared with the mobilized armies of the European powers. The federal army was under 100,000 men, while the National Guard, the organized militias of the states, numbered around 120,000. By 1916, it had become clear that any American participation in the European conflict would require a far larger fighting force. The National Defense Act of 1916 authorized the growth of the army to 165,000 and the National Guard to 450,000 by 1921, but by 1917 the federal army had only expanded to around 121,000, with the National Guard numbering 181,000.

While President Wilson initially wished to only use volunteers, it soon became clear this would not meet the need; three weeks after war was declared, only 97,000 had volunteered for service. Wilson therefore accepted the recommendation from Secretary of War Newton D. Baker to institute a draft. General Enoch Crowder, the U.S. Army’s Judge Advocate General, indicated his displeasure with the plan. Yet not only did Crowder guide the bill through Congress with the assistance of Captain Hugh Johnson and others, he also went on to administer the draft in the position of provost marshal general.

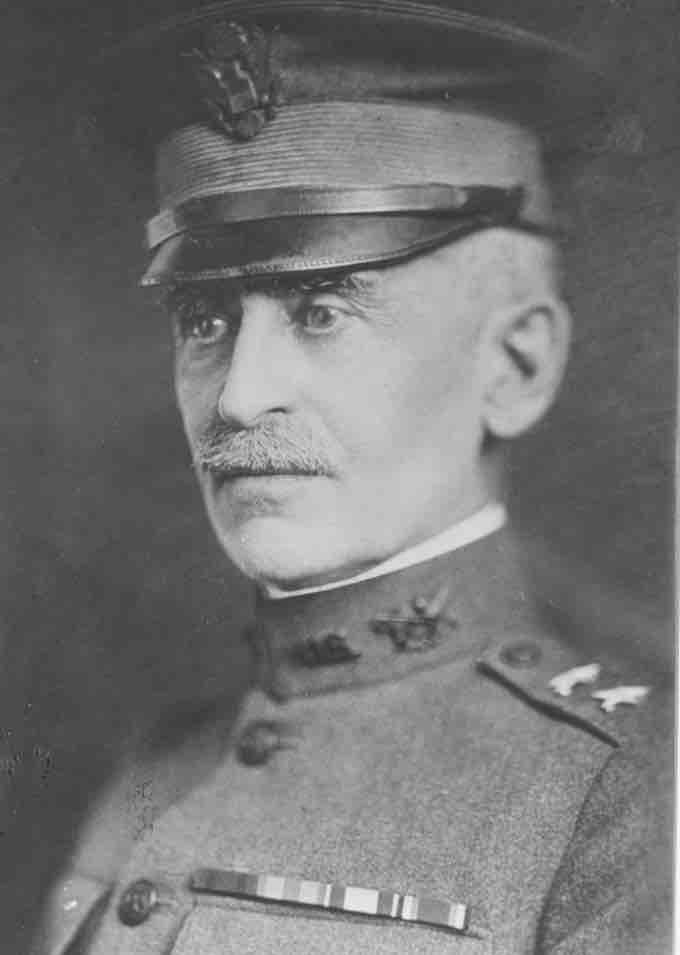

General Enoch Crowder

Initially opposed to the draft, Crowder took charge of administrating the draft in the post of provost marshal general.

Success of the Draft

Under the Selective Service Act of 1917, all males aged 21 to 30 were required to register for military service. Congress amended the law in August 1918 at the War Department’s request to expand the age range to include all men 18 to 45, and to end further volunteering.

One notable problem that arose in the writing and passage of the bill was former President Theodore Roosevelt’s desire to utilize a wholly volunteer fighting force in Europe, similar to the so-called Rough Riders cavalry regiment in which he served during the Spanish-American War in Cuba. Wilson and others, especially army officers, were reluctant primarily because these men would serve under Roosevelt rather than the established U.S. Army and Navy chain of command, but also because of Roosevelt’s intention to raise one or two regiments of African-American soldiers. The final bill contained a compromise provision permitting the president to raise four separate volunteer divisions, although Wilson neglected to exercise this power.

Approximately 2 million men volunteered to serve in the existing branches of the armed forces, while another 2.8 million were drafted into service by the end of the war, with fewer than 350,000 men "dodging" the draft, likely because of the patriotic fervor that swept the country. The U.S. Congress further supplemented the military by drafting Puerto Ricans as part of the March 1917 Jones-Shafroth Act, which granted U.S. citizenship, created a senate, and established a bill of rights for residents of Puerto Rico.

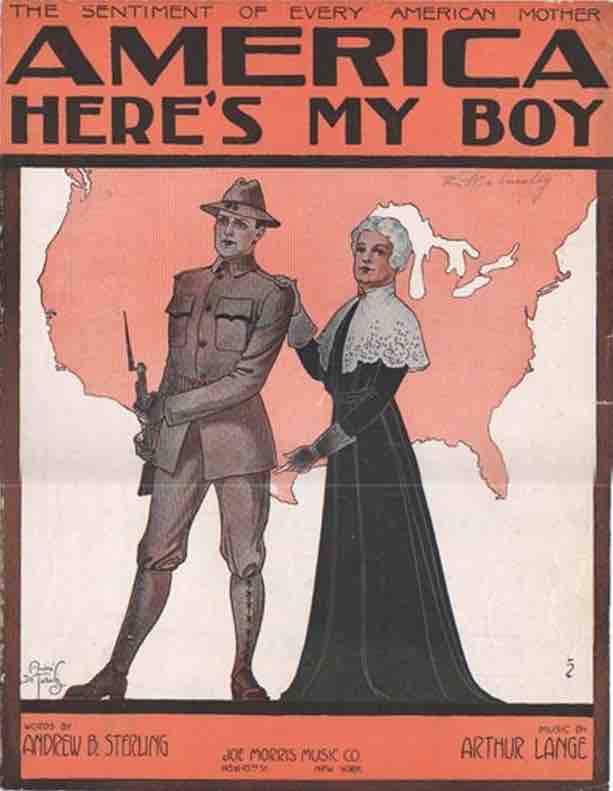

"America, Here's My Boy"

Sheet music cover for "America Here's My Boy", words by Andrew B. Sterling, music by Arthur Lange. Patriotic fervor is often cited as a reason for the high success rate of the World War I draft.

Draft Registration, 1917

Young men registering for military conscription in New York City, June 5, 1917.

"Associated Power" and the AEF

The United States never formally signed on as a member of the Allies in World War I, but instead nominated itself to be an "associated power" to France and Great Britain in order to avoid "foreign entanglements", which was longstanding American foreign policy. American entry into the war, therefore, was taken up by what became known as the American Expeditionary Force.

American Expeditionary Force

Officers of the American Expeditionary Force, who would become crucial to the Allied war in Europe by 1918.

In May 1917, President Wilson appointed Major General John J. Pershing as the U.S. armed forces commander. Yet Pershing required that his soldiers were fully trained before going to Europe, resulting in few arriving before 1918. The first American troops, often called "Doughboys", numbered 14,000 in France by June 1917, and grew to a force of over 1 million by May 1918, half of them on the front lines.

Transport ships needed to bring American troops to Europe were scarce at the beginning, forcing the army to press cruise ships into service, as well as borrowing Allied ships to transport soldiers from New York, New Jersey, and Newport News, Virginia. They also used captured German vessels. The mobilization effort taxed the American military to the limit and required new organizational strategies and command structures to transport great numbers of troops and supplies quickly and efficiently. French harbors became the entry points into the railway system, which brought U.S. forces and their supplies to the front. American engineers in France built 82 new ship berths, nearly 1,000 miles of additional standard-gauge tracks, and 100,000 miles of telephone and telegraph lines.

Germany miscalculated how quickly the U.S. could mobilize after its declaration of war, believing many months would pass before the bulk of American soldiers arrived and that their transports could be stopped by the Kaiser’s fleet of submersible U-boats. Yet the 1st Division, a formation of experienced regular soldiers and the first combat group to arrive in France, entered the trenches near Nancy in late October 1917.

From 1917–1918, the AEF took part in 13 military campaigns against the Imperial German Army alongside French and British forces. The AEF helped the French Army on the Western Front in June 1918 during the Aisne Offensive at Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood, and later that year fought major actions in the Saint-Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. Despite the mixed feelings of Allied leaders who distrusted an army lacking experience in large-scale warfare, Pershing insisted that American forces would not be used merely to fill gaps in the French and British armies or act as replacements in decimated Allied units. He made an exception for African-American combat regiments who were used in used in French divisions, notably the Harlem Hellfighters, who earned a Croix de Guerre unit medal for actions with the French 16th Division at Chateau-Thierry, Sechault and Belleau Wood.

Piave Front, 1918

American soldiers on the Piave Front in 1918 hurling hand grenades into the Austrian trenches.