Overview

"Black Power" is a term used to refer to various ideologies associated with African Americans in the United States, emphasizing racial pride and the creation of black political and cultural institutions to nurture and promote black collective interests and advance black values. Black Power expresses a range of political goals, from defense against racial oppression to the establishment of social institutions and a self-sufficient economy.

Background

The episodes of violence that accompanied Martin Luther King Jr.’s murder were but the latest in a string of urban protests since the mid-1960s. Between 1964 and 1968, there were 329 protests in 257 cities across the nation. In 1965, a traffic stop set in motion a chain of events that culminated in violence in Watts, an African American neighborhood in Los Angeles. Thousands of businesses were destroyed, and, by the time the violence ended, 34 people were dead, most of them African Americans killed by the Los Angeles police and the National Guard.

Frustration and anger lay at the heart of these protests. Despite the programs of the Great Society, essentials such as good healthcare, job opportunities, and safe housing were abysmally lacking in urban African American neighborhoods in cities throughout the country, including in the North and West, where discrimination was less overt but just as crippling. In the eyes of many protesters, the federal government either could not or would not end their suffering, and most existing civil rights groups and their leaders had been unable to achieve significant results toward racial justice and equality. Disillusioned, many African Americans turned to those with more radical ideas about how best to obtain equality and justice.

Stokely Carmichael

Within the chorus of voices calling for integration and legal equality were many that more stridently demanded empowerment and thus supported Black Power. Black Power meant a variety of things. One of the most famous users of the term was Stokely Carmichael, the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who later changed his name to Kwame Ture. For Carmichael, Black Power was the power of African Americans to unite as a political force and create their own institutions apart from white-dominated ones, an idea first suggested in the 1920s by political leader and orator Marcus Garvey. Like Garvey, Carmichael became an advocate of black separatism, arguing that African Americans should live apart from whites and solve their problems for themselves. In keeping with this philosophy, Carmichael expelled SNCC’s white members. In 1966, Carmichael began urging African American communities to confront the Ku Klux Klan armed and ready for battle; he felt it was the only way to ever rid the communities of the terror caused by the Klan. He left SNCC in 1967 and later joined the Black Panthers.

Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael is often associated with the Black Power movement.

Malcolm X

Long before Carmichael began to call for separatism, the Nation of Islam, founded in 1930, had advocated the same thing. In the 1960s, its most famous member was Malcolm X, born Malcolm Little. The Nation of Islam advocated the separation of white Americans and African Americans because of a belief that African Americans could not thrive in an atmosphere of white racism. Indeed, in a 1963 interview, Malcolm X, discussing the teachings of the head of the Nation of Islam in America, Elijah Muhammad, referred to white people as “devils” more than a dozen times. Rejecting the nonviolent strategy of other civil rights activists, he maintained that violence in the face of violence was appropriate.

In 1964, after a trip to Africa, Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam to found the Organization of Afro-American Unity with the goal of achieving freedom, justice, and equality “by any means necessary.” His views regarding black-white relations changed somewhat thereafter, but he remained fiercely committed to the cause of African American empowerment. On February 21, 1965, he was killed by members of the Nation of Islam. Stokely Carmichael later recalled that Malcolm X had provided an intellectual basis for Black Nationalism and given legitimacy to the use of violence in achieving the goals of Black Power.

Differing Approaches

This move toward Black Power and self-defense as a means of obtaining African-American civil rights marked a change from previous nonviolent actions. Martin Luther King, Jr. was not comfortable with the "Black Power" slogan, which sounded too much like black nationalism to him. SNCC activists, in the meantime, began embracing the "right to self-defense" in response to attacks from white authorities and disagreed with King for continuing to advocate nonviolence.

When King was murdered in 1968, Stokely Carmichael stated that whites murdered the one person who would prevent rampant rioting, and that blacks would burn every major city to the ground. Racial riots broke out in the black community in cities from Boston to San Francisco following King's death. As a result, the white population fled from many areas in these cities and city crews were often hesitant to enter affected areas, leaving Blacks in dilapidated cities.

The Black Power movement was given a stage on live, international television on October of 1968. Tommie Smith and John Carlos, while being awarded the gold and bronze medals at the 1968 Summer Olympics, donned human rights badges and each raised a black-gloved Black Power salute during their podium ceremony. Smith and Carlos were immediately ejected from the games by the United States Olympic Committee, and the International Olympic Committee would later issue a permanent lifetime ban for the two.

The self-empowerment philosophy of Black Power influenced mainstream civil rights groups such as the National Economic Growth Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO), which sold bonds and operated a clothing factory and construction company in New York, and the Opportunities Industrialization Center in Philadelphia, which provided job training and placement—by 1969, it had branches in seventy cities.

Black Power salute

The Black Power salute was a noted human rights protest and one of the most overtly political statements in the 110-year history of the modern Olympic Games. African American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos performed their Black Power salute at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City while receiving their medals and were subsequently ejected from the games.

The Black Panther Party

Black Power was made most public by the Black Panther Party, which was founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California, in 1966 . This group followed the ideology of Malcolm X using a "by-any-means necessary" approach to stopping inequality. Unlike Carmichael and the Nation of Islam, most Black Power advocates did not believe African Americans needed to separate themselves from white society. The Black Panther Party believed African Americans were as much the victims of capitalism as of white racism. Accordingly, the group espoused Marxist teachings and called for jobs, housing, and education, as well as protection from police brutality and exemption from military service in their Ten Point Program. Their militant attitude and advocacy of armed self-defense attracted many young men but also led to many encounters with the police, which sometimes included arrests and even shootouts, such as those that took place in Los Angeles, Chicago and Carbondale, Illinois.

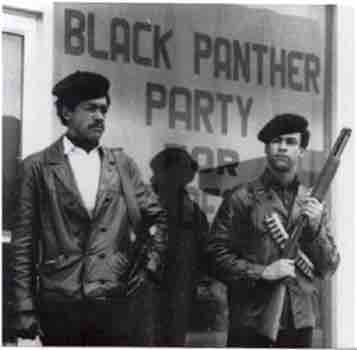

Black Panther Party

Black Panther Party members standing in the street, armed with a Colt .45 and a shotgun.

The organization's official newspaper, The Black Panther, was first circulated in 1967. That same year, the Black Panther Party marched on the California State Capitol in Sacramento in protest of a selective ban on weapons. By 1968, the party had expanded into many cities throughout the United States. Peak membership was near 10,000 by 1969, and their newspaper had a circulation of 250,000.

Gaining national prominence, the Black Panther Party became an icon of the counterculture of the 1960s. They instituted a variety of community social programs designed to alleviate poverty, improve health among inner city black communities, and soften the Party's public image. The Black Panther Party's most widely known programs were its Free Breakfast for Children program and its armed citizens' patrols of the streets of African American neighborhoods to protect residents from police brutality. However, the group's political goals were often overshadowed by their confrontational, militant, and violent tactics against police.

Impact of the Black Power Movement on African-American Identity

White fear and racialized backlash to groups such as the Black Panthers led to a great deal of biased media coverage, and the Black Power movement gained a negative and militant reputation. Many people felt that this movement of "insurrection" would soon serve to cause discord and disharmony through the entire country - even though discord and disharmony had existed for African Americans since their early subjugation in the Americas.

Though Black Power at the most basic level refers to a political movement, Black Power was also part of a much larger process of cultural change. The 1960s composed a decade not only of Black Power but also of Black Pride. African American abolitionist John S. Rock had coined the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” in 1858, but in the 1960s, it became an important part of efforts within the African American community to raise self-esteem and encourage pride in African ancestry. Black Pride urged African Americans to reclaim their African heritage and, to promote group solidarity, to substitute African and African-inspired cultural practices, such as handshakes, hairstyles, and dress, for white practices.

The movement uplifted the black community as a whole by cultivating feelings of racial solidarity, often in opposition to the world of white Americans - a world that had oppressed Blacks for generations. Through the movement, Blacks came to understand themselves and their culture by exploring and debating the question "who are we?", in order to establish unified and viable identities. The respect and attention accorded to African Americans' history and culture in both formal and informal settings today is largely a product of the movement for Black Power in the 1960s and 1970s.