John F. Kennedy and Civil Rights

The turbulent issue of state-sanctioned racial discrimination was one of the most pressing domestic issues for the Kennedy administration in the 1960s. John F. Kennedy verbally supported racial integration and civil rights in many instances. In a 1961 speech, Kennedy expressed the administration's commitment: " We will not stand by or be aloof—we will move. I happen to believe that the 1954 [Supreme Court school desegregation] decision was right. But my belief does not matter. It is now the law. Some of you may believe the decision was wrong. That does not matter. It is the law."

Robert Kennedy and Civil Rights

It has become commonplace to assert the phrase "the Kennedy Administration" or even "President Kennedy" when discussing the legislative and executive support of the civil rights movement. However, between 1960 and 1963, many of the initiatives that occurred during President John F. Kennedy's tenure were a result of the passion and determination of Attorney General Robert Kennedy, who through his rapid education in the realities of Southern racism, underwent a thorough conversion of purpose. Asked in May of 1962, "What do you see as the big problem ahead for you, is it crime or internal security?" Robert Kennedy replied, "Civil Rights." The president came to share his brother's sense of urgency on the matters at hand to such an extent that it was at the Attorney General's insistence that he made his famous address to the nation.

Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Attorney General Kennedy and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 22 June 1963, Washington, D.C. Robert Kennedy demonstrated federal support for the civil rights movement.

Tentative Steps Toward Civil Rights

Cold War concerns, which guided U.S. policy in Cuba and Vietnam, also motivated the Kennedy administration’s steps toward racial equality. Realizing that legal segregation and widespread discrimination hurt the country’s chances of gaining allies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the federal government increased efforts to secure the civil rights of African Americans in the 1960s. During his presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy had intimated his support for civil rights, and his efforts to secure the release of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., who was arrested following a demonstration, won him the African American vote. Lacking widespread backing in Congress, however, and anxious not to offend white southerners, Kennedy was cautious in assisting African Americans in their fight for full citizenship rights.

Voter Registration

His strongest focus was on securing the voting rights of African Americans. President Kennedy feared the loss of support from southern white Democrats and the impact a struggle over civil rights could have on his foreign policy agenda as well as on his reelection in 1964. However, he thought voter registration drives were far preferable to the boycotts, sit-ins, and integration marches that had generated such intense global media coverage in previous years. Encouraged by Congress’s passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1960, which permitted federal courts to appoint referees to guarantee that qualified persons would be registered to vote, Kennedy focused on the passage of a constitutional amendment outlawing poll taxes, a tactic that southern states used to disenfranchise African American voters. Originally proposed by President Truman’s Committee on Civil Rights, the idea had been largely forgotten during Eisenhower’s time in office. Kennedy, however, revived it and convinced Spessard Holland, a conservative Florida senator, to introduce the proposed amendment in Congress. It passed both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification in September 1962.

Freedom Riders

Robert Kennedy played a large role in the Freedom Riders protests. After the bus bombings in Anniston, Alabama, Kennedy sent John Seigenthaler, his administrative assistant, to Alabama to secure the riders' safety. He also forced the Greyhound bus company to provide the Freedom Riders with a bus driver to ensure they could continue their journey.

While Kennedy offered protection to the Freedom Riders, he also attempted to convince them to end the Rides. Kennedy's attempts to end the Freedom Rides early were in many ways tied to broader international issues and an upcoming summit with Khrushchev and De Gaulle; he believed the continued international publicity of race riots would tarnish the president heading into international negotiations. This reluctance to advance and continue to protect the Freedom Rides alienated many of the Civil Rights leaders at the time who perceived him as intolerant and narrow-minded.

Despite this, Robert Kennedy intervened on behalf of the civil rights activists on numerous occasions. Robert Kennedy saw voting as the key to racial justice, and collaborated with Presidents Kennedy and Johnson to create the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, which helped bring an end to Jim Crow laws.

The Integration of Universities

In September of 1962, a student named James Meredith enrolled at the University of Mississippi but was prevented from entering. He attempted to enter campus on September 20, on September 25, and again on September 26. He was blocked by Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett, who said, "[N]o school will be integrated in Mississippi while I am your Governor."

Robert Kennedy responded by sending 400 federal marshals, hoping that legal means, along with the escort of U.S. Marshals, would be enough to force the governor to allow Meredith admission. On September 30, 1962, Meredith entered the campus under their escort. White students and other local whites began rioting that evening, throwing rocks and then firing on the U.S. Marshals guarding Meredith at Lyceum Hall. Two people, including a French journalist, were killed; 28 marshals suffered gunshot wounds, and 160 others were injured. After the violent turn of events, President John F. Kennedy sent 3,000 troops to quell the riot; once the situation was contained, Meredith finally enrolled in his first class. On November 20, 1962, President Kennedy signed Executive Order 11063, prohibiting racial discrimination in federally supported housing or "related facilities."

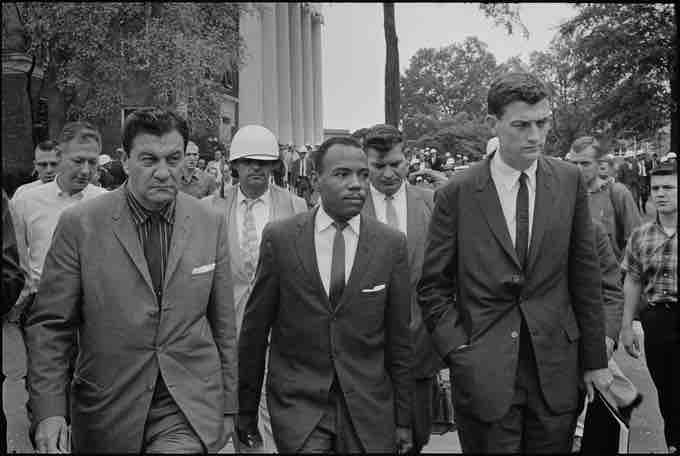

James Meredith

James Meredith walking to class accompanied by U.S. marshals

Similarly, on June 11, 1963, President Kennedy intervened when Alabama Governor George Wallace blocked the doorway to the University of Alabama to stop two African American students, Vivian Malone and James Hood, from attending. President Kennedy sent a force to make Governor Wallace step aside.

That evening, Kennedy gave his famous civil rights address on national television and radio, launching his initiative for civil rights legislation—to provide equal access to public schools and other facilities and greater protection of voting rights. Kennedy proposed a bill that would give the federal government greater power to enforce school desegregation, prohibit segregation in public accommodations, and outlaw discrimination in employment. Kennedy would not live to see his bill enacted; however, it would become law during Lyndon Johnson’s administration as the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Throughout this time, both Robert Kennedy and John F. Kennedy remained adamant concerning the rights of black students to enjoy the benefits of all levels of the educational system.

Wallace Opposing Federal Intervention

Alabama governor George Wallace stands against desegregation at the University of Alabama and is confronted by U.S. Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbachat in 1963.

Interventions in the Birmingham Campaigns, 1963-1964

In 1963, activists made plans to desegregate downtown Birmingham merchants. The campaign used a variety of nonviolent methods of confrontation, including sit-ins, kneel-ins at local churches, and a march to the county building to mark the beginning of a drive to register voters. The city, however, obtained an injunction barring all such protests. Convinced that the order was unconstitutional, the campaign defied it and prepared for mass arrests of its supporters. King elected to be among those arrested on April 12, 1963.

Widespread public outrage led the Kennedy administration to directly and more forcefully intervene in negotiations between the white business community and the activists. On May 10, the parties announced an agreement to desegregate the lunch counters and other public accommodations downtown; to create a committee to eliminate discriminatory hiring practices; to arrange for the release of jailed protesters; and to establish regular means of communication between black and white leaders.