The Rise of Second-Wave Feminism

Women's movements of the late 19th and early 20th century (later known as first-wave feminism) focused primarily on overturning legal obstacles to gender equality, such as voting rights and property rights. In contrast, the second wave of feminism in the 1960s, inspired and galvanized by the civil rights movement of the same era, broadened the debate of women's rights to encompass a wider range of issues, including sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, de facto inequalities, and official legal inequalities. Second-wave feminism radically changed the face of western culture, leading to marital rape laws, the establishment of rape crisis and battered women's shelters, significant changes in custody and divorce law, and widespread integration of women into sports activities and the workplace. It also tried and failed to add the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Background

On the national scene, the civil rights movement was creating a climate of protest and claiming rights and new roles in society for people of color. Women played significant roles in organizations fighting for civil rights like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); however, they often found that those organizations, enlightened as they might be about racial issues or the war in Vietnam, could still be influenced by patriarchal ideas of male superiority. Two members of SNCC, Casey Hayden and Mary King, presented some of their concerns about their organization’s treatment of women in a document entitled “On the Position of Women in SNCC.”

Just as the abolitionist movement made nineteenth-century women more aware of their lack of power and encouraged them to form the first women’s rights movement, the protest movements of the 1960s inspired many white and middle-class women to create their own organized movement for greater rights. Not all were young women engaged in social protest. Many were older, married women who found the traditional roles of housewife and mother unfulfilling. In 1963, writer and feminist Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique in which she contested the post-World War II belief that it was women’s destiny to marry and bear children. The perfect nuclear family image depicted and strongly marketed at the time, she wrote, did not reflect happiness and was rather degrading for women. Friedan’s book was a best-seller and began to raise the consciousness of many women who agreed that homemaking in the suburbs sapped them of their individualism and left them unsatisfied.

Betty Friedan

Betty Friedan, American feminist and writer, author of "The Feminine Mystique"

Key Events in the Second Wave of Feminism

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in employment on the basis of race, color, national origin, and religion, also prohibited, in Title VII, discrimination on the basis of sex. Ironically, protection for women had been included at the suggestion of a Virginia congressman in an attempt to prevent the act’s passage; his reasoning seemed to be that, while a white man might accept that African Americans needed and deserved protection from discrimination, the idea that women deserved equality with men would be far too radical for any of his male colleagues to contemplate. Nevertheless, the act passed, although the struggle to achieve equal pay for equal work continues today.

Birth Control

Medical science also contributed a tool to assist women in their liberation. In 1960, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill, freeing women from the restrictions of pregnancy and childbearing. Women who were able to limit, delay, and prevent reproduction were freer to work, attend college, and delay marriage. Within five years of the pill’s approval, some six million women were using it. The pill was the first medicine ever intended to be taken by people who were not sick. Even conservatives saw it as a possible means of making marriages stronger by removing the fear of an unwanted pregnancy and improving the health of women. Its opponents, however, argued that it would promote sexual promiscuity, undermine the institutions of marriage and the family, and destroy the moral code of the nation. By the early 1960s, thirty states had made it a criminal offense to sell contraceptive devices.

The Equal Pay Act

In 1963, Kennedy's Commission released a report detailing discrimination against women in every aspect of American life and outlined plans to achieve equality. Specific recommendations for women in the workplace included fair hiring practices, paid maternity leave, and affordable childcare. The Equal Pay Act at this time proposed, but had no way of enforcing, equality of pay for men and women performing equal work. In addition, it did not cover domestic workers, agricultural workers, executives, administrators, or professionals.

The National Organization for Women

In 1966, the National Organization for Women (NOW) was formed by 28 women—among them Betty Friedan—and proceeded to set an agenda for the feminist movement. Framed by a statement of purpose written by Friedan, who became its first president, the agenda began by proclaiming NOW’s goal to make possible women’s participation in all aspects of American life and to gain for them all the rights enjoyed by men. Among the specific goals was the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (yet to be adopted). The group was the largest women's group in the U.S. and pursued its goals through extensive legislative lobbying, litigation, and public demonstrations.

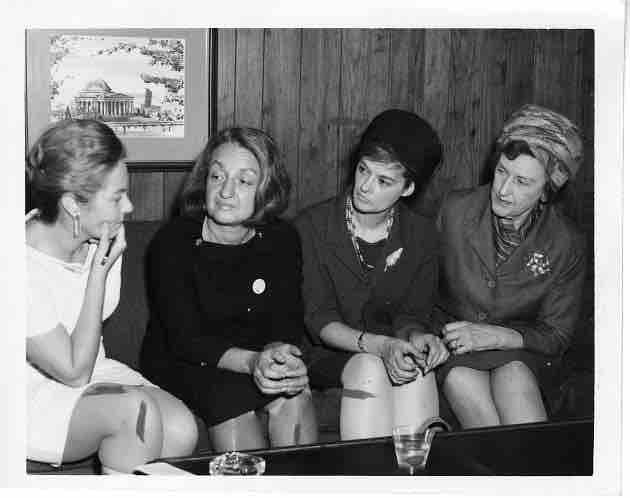

Leaders of NOW

National Organization for Women (NOW) founder and president Betty Friedan; NOW co-chair and Washington, D.C., lobbyist Barbara Ireton; and feminist attorney Marguerite Rawalt.

Radical Movements

More radical feminists, like their colleagues in other movements, were dissatisfied with merely redressing economic issues and devised their own brand of consciousness-raising events and symbolic attacks on women’s oppression. The most famous of these was an event staged in September 1968 by New York Radical Women. Protesting stereotypical notions of femininity and rejecting traditional gender expectations, the group demonstrated at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to bring attention to the contest’s—and society’s—exploitation of women. The protestors crowned a sheep Miss America and then tossed instruments of women’s oppression, including high-heeled shoes, curlers, girdles, and bras, into a “freedom trash can.” News accounts famously, and incorrectly, described the protest as a “bra burning." By 1969, the radical organization Redstockings popularized slogans such as "Sisterhood is Powerful" and "The Personal is Political," which became buzzwords of the feminist movement.

Women's Liberation March

A Women's Liberation march in Washington, D.C., 1970