The Election of 1824

John Quincy Adams was elected president on February 9, 1825, in the United States presidential election of 1824, after the election was decided by the House of Representatives. The presidential election of 1824 is notable for being the only election since the passage of the Twelfth Amendment to have been decided by the House of Representatives. The Twelfth Amendment, passed in 1804, addressed concerns that had arisen in the elections of 1796 and 1800 and stated that an election would be turned over to the House if no candidate secured a majority of the electoral vote. The election of 1824 is often claimed to be the first in which the successful presidential candidate did not win the popular vote; however, the popular vote was not measured nationwide at the time, making this claim somewhat speculative.

General Election

Campaign

The presidential election of 1824 featured five candidates, all of whom ran as Democratic-Republicans (the Federalists having ceased to be a national political force). The crowded field included John Quincy Adams, the son of the second president, John Adams. Candidate Adams had broken with the Federalists in the early 1800s and served on various diplomatic missions, including the mission to secure peace with Great Britain in 1814. He represented New England. A second candidate, John C. Calhoun from South Carolina, had served as secretary of war and represented the slaveholding South. He dropped out of the presidential race to run for vice president. A third candidate, Henry Clay, the speaker of the House of Representatives, hailed from Kentucky and represented the western states. He favored an active federal government committed to internal improvements, such as roads and canals, to bolster national economic development and settlement of the West. William H. Crawford, a slaveholder from Georgia, suffered a stroke in 1823 that left him largely incapacitated, but he ran nonetheless and had the backing of the New York machine headed by Martin Van Buren. Andrew Jackson, the famed “hero of New Orleans,” rounded out the field. Jackson had very little formal education, but he was popular for his military victories in the War of 1812 and in wars against the Creek and the Seminole. He had been elected to the Senate in 1823, and his popularity soared as pro-Jackson newspapers extolled the courage and daring of the Tennessee slaveholder.

The election was as much a contest of favorite sons as it was a conflict over policy, although positions on tariffs and internal improvements did create some significant disagreements. In general, the candidates were favored by different sections of the country, with Adams strong in the Northeast; Jackson in the South, West, and mid-Atlantic; Clay in parts of the West; and Crawford in parts of the East.

Results

With tens of thousands of new voters, the older system of having members of Congress form congressional caucuses to determine who would run no longer worked. The new voters had regional interests and voted on them. For the first time, the popular vote mattered in a presidential election. Electors were chosen by popular vote in eighteen states, while the six remaining states used the older system in which state legislatures chose electors.

Results from the eighteen states where the popular vote determined the electoral vote gave Jackson the election, with 152,901 votes to Adams’s 114,023, Clay’s 47,217, and Crawford’s 46,979. The Electoral College, however, was another matter. Of the 261 electoral votes, Jackson needed 131 or more to win but secured only 99. Adams won 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. Meanwhile, John C. Calhoun secured a total of 182 electoral votes and won the vice presidency in what was generally an uncompetitive race.

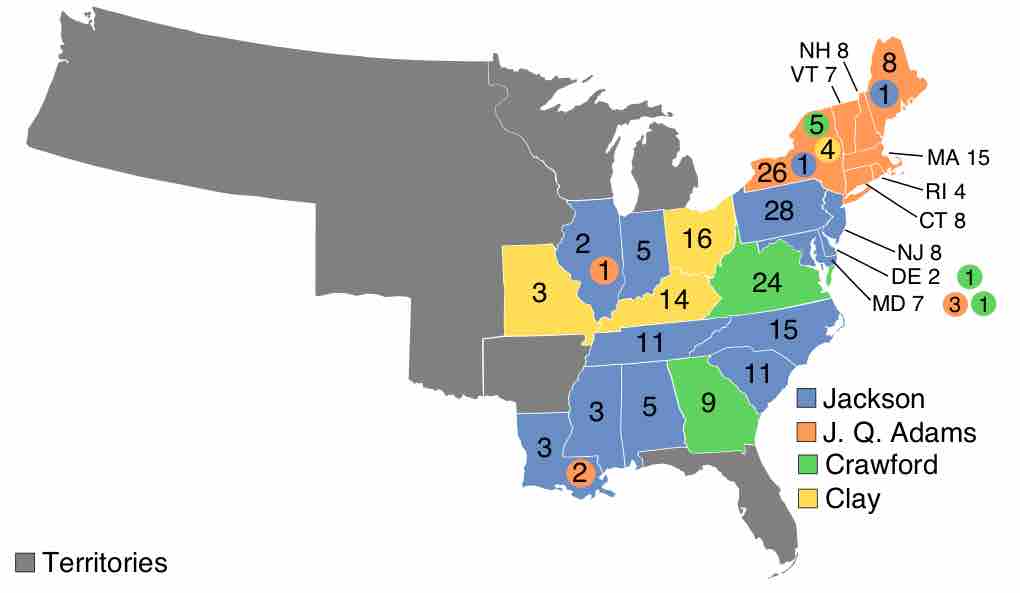

Electoral College votes in the election of 1824

This map of the Electoral College votes of 1824 illustrates the number of electoral votes allotted to each candidate in each state.

1825 Contingent Election

Because Jackson did not receive a majority vote from the Electoral College, the election was decided following the terms of the Twelfth Amendment, which stipulated that when a candidate did not receive a majority of electoral votes, the election went to the House of Representatives, where each state would provide one vote. Following the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment, only the top three candidates in the electoral vote were admitted as candidates in the House: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and William Harris Crawford.

House Speaker Clay did not want to see his rival, Jackson, become president and therefore worked within the House to secure the presidency for Adams, convincing many to cast their vote for the New Englander. Clay’s efforts paid off; despite not having won the popular vote, John Quincy Adams was certified by the House as the next president on February 9, 1825, on the first ballot with 13 states, followed by Jackson with 7 and Crawford with 4. Once in office, Adams elevated Henry Clay to the post of secretary of state.

Adams's victory shocked Jackson who, as the winner of a plurality of both the popular and electoral votes, expected to be elected president. Jackson and his followers accused Adams and Clay of striking a corrupt bargain. The Jacksonians would campaign on this claim for the next four years, ultimately attaining Jackson's victory in the Adams-Jackson rematch of 1828.

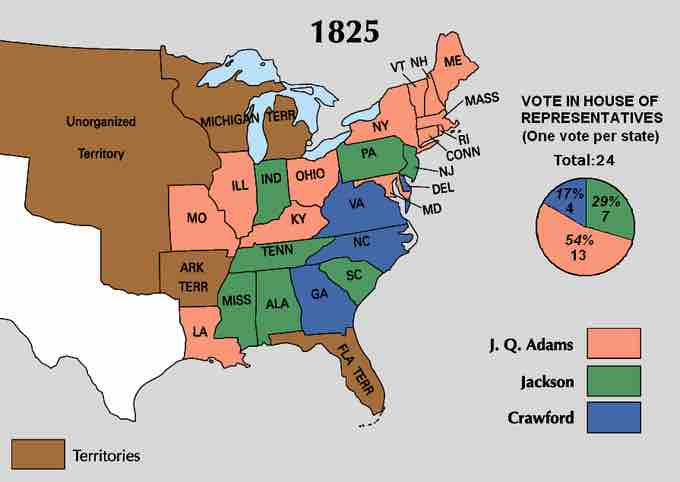

House of Representatives votes in the election of 1824

This map illustrates the voting for candidates by state in the House of Representatives election of 1824. Adams, despite not winning the popular vote, won 54 percent of the House votes and was elected president in 1825.