Introduction

The relationship between business and labor has been at the center of some of the major economic and political theories about capitalism over the last two centuries. In his 1867 work, Das Kapital, Karl Marx argued that business and labor were inherently at odds under capitalism, because the motivating force of capitalism is in the exploitation of labor, whose unpaid work is the ultimate source of profit and surplus value. In order for this tension to be resolved, the workers had to take ownership over the means of the production, and, therefore, their own labor–a process that Marx explained in his other major work, The Communist Manifesto.

The late nineteenth century saw many governments starting to address questions surrounding the relationship between business and labor, primarily through labor law or employment law. Labor law is the body of laws, administrative rulings, and precedents which address the legal rights of, and restrictions on, working people and their organizations. As such, it mediates many aspects of the relationship between trade unions, employers, and employees.

Labor and Business

Labor strikes, such as this one in Tyldesley in the 1926 General Strike in the U.K., represent the often fraught relationship between labor and business.

Labor Law

Labor law arose due to the demand for workers to have better conditions, the right to organize, or, alternatively, the right to work without joining a labor union, and the simultaneous demands of employers to restrict the powers of the many organizations of workers and to keep labor costs low. Employers' costs can increase due to workers organizing to achieve higher wages, or by laws imposing costly requirements, such as health and safety or restrictions on their free choice of whom to hire . Workers' organizations, such as trade unions, can also transcend purely industrial disputes and gain political power. The state of labor law at any one time is, therefore, both the product of, and a component of, struggles between different interests in society.

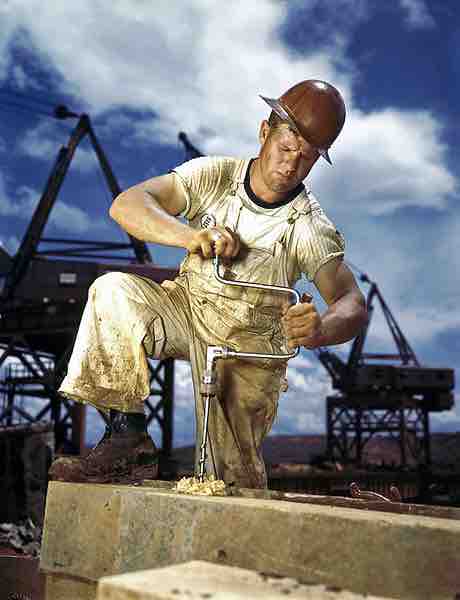

Palmer Carpenter

1942 photograph of a carpenter at work on Douglas Dam, Tennessee (TVA). Encyclopedic both as a document of carpentry during that era and as a historic example of early color photography. Supersaturation was popular in the United States during that era; a fine example of the esthetics of its place and time.

The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 set the maximum standard work week to 44 hours and in 1950, this was reduced to 40 hours. A green card entitles legal immigrants to work just like U.S. citizens, without requirement of work permits. Despite the 40-hour standard maximum work week, some lines of work require more than 40 hours to complete the tasks of the job. For example, if you prepare agricultural products for market, you can work over 72 hours a week, if you want to, but you cannot be required to work these many hours. If you harvest products you must get a period of 24 hours off after working up to 72 hours in a seven-day period. There are exceptions to the 24-hour break period for certain harvesting employees, such as those involved in harvesting grapes, tree fruits, and cotton. Professionals, clerical (administrative assistants), technical, and mechanical employees cannot be terminated for refusing to work more than 72 hours in a work week. These high-hour ceilings, combined with a competitive job market, often motivate American workers to work more hours than required. American workers consistently take fewer vacation days than their European counterparts and on average, take the fewest days off of any developed country.

Commercial Law

Commercial law is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of persons and businesses engaged in commerce, merchandising, trade, and sales. It is often considered to be a branch of civil law and deals with issues of both private law and public law.