Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes critical to the innate immune system. The role of NK cells is similar to that of cytotoxic T cells in the adaptive immune response. NK cells provide rapid responses to virus-infected cells and respond to tumor formation by destroying abnormal and infected cells. NK cells use wo cytolytic granule-mediated apoptosis to destroy abnormal and infected cells.

Natural Killer Overview

Typically, immune cells detect major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presented on cell surfaces, triggering cytokine release and lysis or apoptosis in cells that do not express MHC I or express much less of it than normal cells. Unlike phagocytes, NK cells do not need their targets to be opsonized (marked) by antibodies before they can act, allowing for a much faster immune reaction. However, opsonins do speed up the process.

These cells named "natural killers" because they were thought to work without cytokine or chemokine activation. However, later research proved that cytokines play a role in guiding NK cells to stressed cells that may need to be destroyed.

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes derived from the common lymphoid progenitor cells (lymphoblasts), which also generate B and T lymphocytes. NK cells differentiate and mature in the bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils and thymus, where they then enter into the bloodstream.

MHC I Recognition

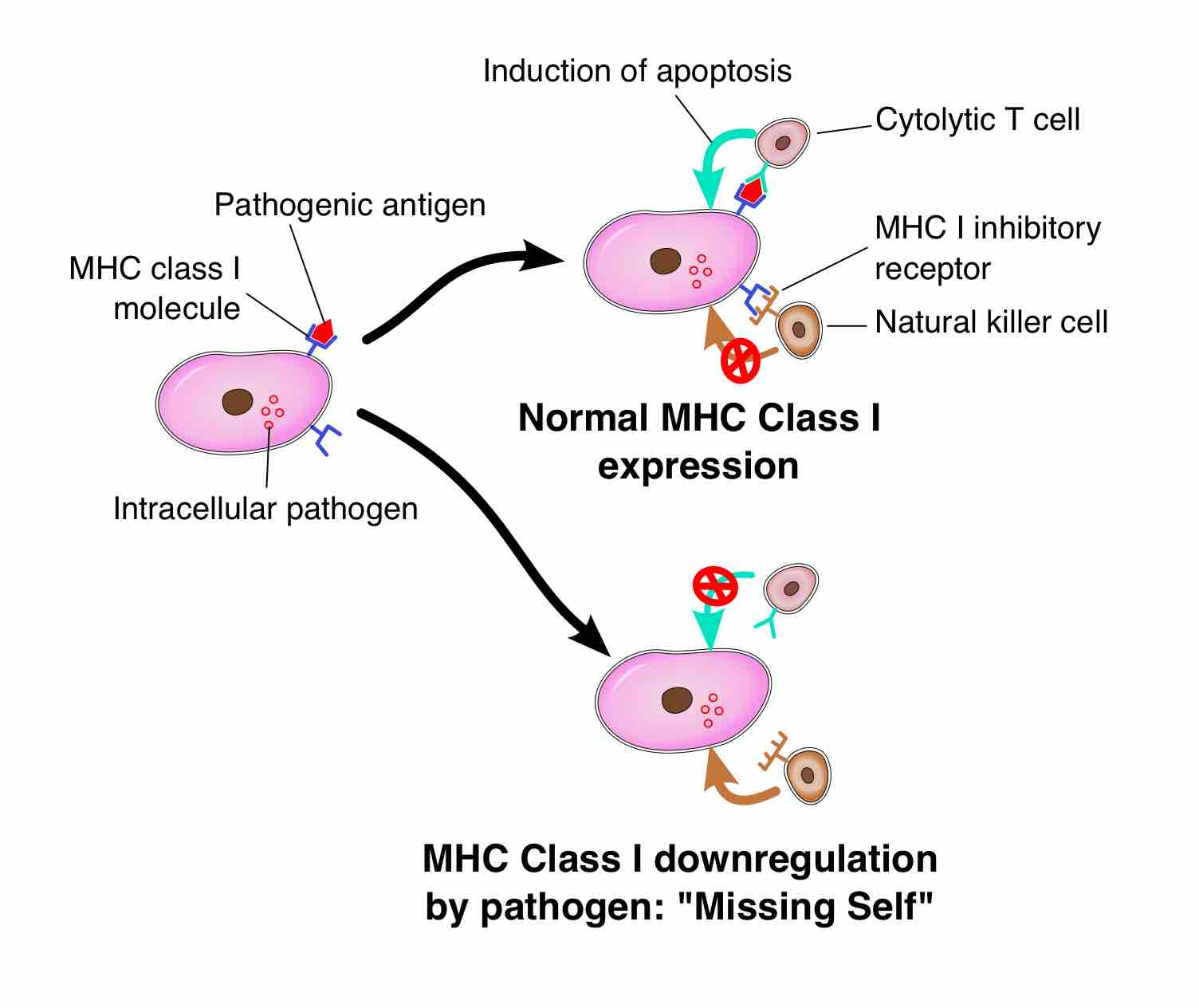

In order for NK cells to defend the body against viruses and pathogens, they require mechanisms to determine whether a cell is infected. The exact mechanisms remain the subject of current investigation, but recognition of an "altered self" state is thought to be involved. To control their cytotoxic activity, NK cells possess two types of surface receptors: activating receptors and inhibitory receptors. Most of these receptors are also present in certain T cells. These receptors recognize major histocompatability complex I (MHC I), a molecule expressed on every cell to signal that the cell belongs to the body.

When the NK cell recognizes MHC I on a cell using an inhibitory receptor, its killing response is inhibited. When the NK cell does not recognize MHC I on the cell with an inhibitory receptor, or detects an antigen with an activating receptor, the killing response is activated. Virus-infected cells and foreign pathogens such as bacteria and fungi will not express the MHC I specific to the host organism, which will fail to inhibit the NK cell's killing responses. If both types of receptors are being stimulated, the receptor that experiences a higher degree of relative stimulation will determine the NK cell behavior. Some tumor cells may still express MHC I in low amounts, so they may evade NK cell destruction based on the balance of activating and inhibiting stimuli.

Complementary Activities of Cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells

Schematic diagram indicating the complementary activities of cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells. T-cells are activated by recognizing antigens, while NK cells are activated by not recognizing MHC I.

Mechanisms of Cytotoxicity

The granules of NK cells contain proteins such as perforin and proteases known as granzymes. Upon binding to a cell slated for killing, perforin forms pores in the cell membrane of the target cell, creating an aqueous channel through which the granzymes and associated molecules can enter, inducing either apoptosis or osmotic cell lysis (a form of cell necrosis). Defensins, an antimicrobial secreted by NK cells, directly kills bacteria by disrupting its cell walls.

Apoptosis is a form of "programmed cell death" in which the cell is stimulated by the cytotoxic mechanisms to destroy itself. Unlike with lysis, apoptosis does not degrade DNA, and cells are destroyed cleanly and completely on their own. Cellular lysis causes necrosis of that cell, in which the DNA and cell components degrade into debris that must be phagocytized by macrophages. This distinction has many important implications. Virus-infected cells destroyed by cell lysis release their replicated virus particles into the body, which infects other cells. In apoptosis, these virus particles are destroyed. However, cancer cells often develop genetic mechanisms to prevent apoptosis signals from occurring, so cell lysis is generally more effective.

Cells that are osponized with antibodies are easier for NK cells to detect and destroy. Antibodies that bind to antigens can be recognized by FcϒRIII (CD16) receptors (a type of activating receptor), resulting in NK activation, release of cytolytic granules, and consequent cell apoptosis.

Cytokines in NK Cell Activity

Cytokines play a role in NK cell activation. Many cells release cytokines as a result of cellular stress when infected with a virus. Cytokines involved in NK activation include IL-12, IL-15, IL-18, IL-2, and CCL5. NK cells are activated in response to interferons or macrophage-derived cytokines. They serve to contain viral infections while the adaptive immune response generates antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells that can clear the infection.

NK cells also secrete their own cytokines of their own to help facilitate immune responses, generally upon NK cell activation. NK cells work to control viral infections by secreting IFNγ (interferon gamma) and TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha). IFNγ activates macrophages for phagocytosis and lysis while TNFα acts to promote direct NK tumor cell killing. It is also a potent inflammatory mediator that causes long-lasting inflammatory responses and fever in response to more severe infections. Patients deficient in NK cells prove to be more susceptible to most infections than people with normal levels of NK cells, due to a loss of innate immune system function and efficiency.