PAHs

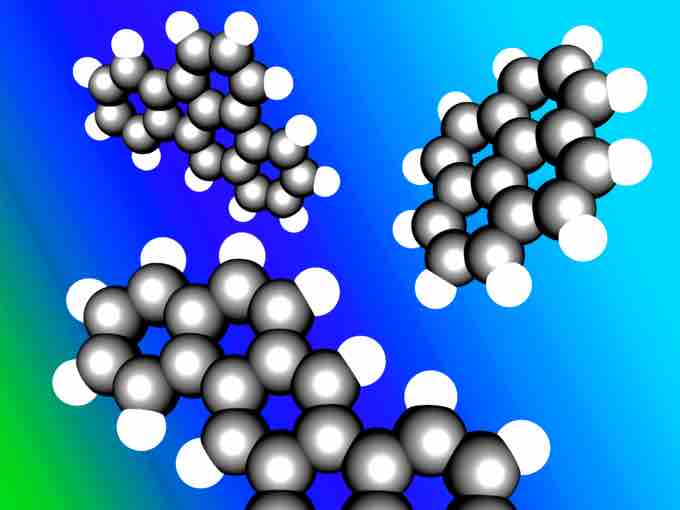

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), also known as poly-aromatic hydrocarbons or polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, are seen in . PAHs are potent atmospheric pollutants that consist of fused aromatic rings and do not contain heteroatoms or carry substituents. Naphthalene is the simplest example of a PAH. PAHs occur in oil, coal, and tar deposits, and are produced as byproducts of fuel burning (whether fossil fuel or biomass). As a pollutant, they are of concern because some compounds have been identified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic. PAHs are also found in cooked foods—studies have found PAHs in meat cooked at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing, and in smoked fish. They are also found in the interstellar medium, comets, and meteorites. PAHs are a candidate for the molecule acted as a basis for the earliest forms of life. In graphene the PAH motif is extended to large 2D sheets.

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

An image showing three examples of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Clockwise from top left, the molecules are: benz[e]acephenanthrylene, pyrene and dibenz[a,h]anthracene.

Natural crude oil and coal deposits contain significant amounts of PAHs from chemical conversion of natural product molecules, such as steroids, to aromatic hydrocarbons. They are also found in processed fossil fuels, tar, and various edible oils.

PLFA Analysis

Phospholipid-derived fatty acids (PLFA) are widely used in microbial ecology as chemotaxonomic markers of bacteria and other organisms. Phospholipids are the primary lipids composing cellular membranes. They can be esterified to many types of fatty acids. Once the phospholipids of an unknown sample are esterfied, the composition of the resulting PLFA can be compared to the PLFA of known organisms to determine the identity of the sample organism. PLFA analysis may be combined with stable isotope probing to determine which microbes are metabolically active in a sample.

The basic premise for PLFA analysis is that as individual organisms (especially bacteria and fungi) die, phospholipids are rapidly degraded and the remaining phospholipid content of the sample is assumed to be from living organisms. As the phospholipids of different groups of bacteria and fungi contain a variety of somewhat unique fatty acids, they can serve as useful biomarkers for such groups. PLFA profiles and composition can be determined by purifying the phospholipids and then cleaving the fatty acids for further analysis.

Bioremediation

Bioremediation is the use of micro-organism metabolism to remove pollutants. Technologies can be generally classified as in situ or ex situ. In situ bioremediation involves treating the contaminated material at the site, while ex situ involves the removal of the contaminated material to be treated elsewhere. Some examples of bioremediation related technologies are phytoremediation, bioventing, bioleaching, landfarming, bioreactor, composting, bioaugmentation, rhizofiltration, and biostimulation.

Bioremediation can occur on its own (natural attenuation or intrinsic bioremediation) or can be spurred on via the addition of fertilizers to increase the bioavailability within the medium (biostimulation). Recent advancements have found success by adding matched microbe strains to the medium to enhance the resident microbe population's ability to break down contaminants. Microorganisms used to perform the function of bioremediation are known as bioremediators. Not all contaminants, however, are easily treated by bioremediation using microorganisms. For example, heavy metals such as cadmium and lead are not readily absorbed or captured by microorganisms. The assimilation of metals such as mercury into the food chain may worsen matters.

Phytoremediation

Phytoremediation is useful in these circumstances because natural plants or transgenic plants are able to bioaccumulate these toxins in their above-ground parts, which are then harvested for removal. The heavy metals in the harvested biomass may be further concentrated by incineration or recycled for industrial use. The elimination of a wide range of pollutants and wastes from the environment requires increasing our understanding of the relative importance of different pathways and regulatory networks to carbon flux in particular environments and for particular compounds, and they will certainly accelerate the development of bioremediation technologies and biotransformation processes.

Mycoremediation

Mycoremediation, is a form of bioremediation, the process of using fungi to degrade or sequester contaminants in the environment. Stimulating microbial and enzyme activity, mycelium reduces toxins in situ. Some fungi are hyperaccumulators, capable of absorbing and concentrating heavy metals in the mushroom fruit bodies. One of the primary roles of fungi in the ecosystem is decomposition, which is performed by the mycelium. The mycelium secretes extracellular enzymes and acids that break down lignin and cellulose, the two main building blocks of plant fiber. These organic compounds are composed of long chains of carbon and hydrogen, structurally similar to many organic pollutants. The key to mycoremediation is determining the right fungal species to target a specific pollutant.

Gallaecimonas is a recently described genus of bacteria. It is a Gram-negative, rod-shaped, halotolerant bacterium in the class Gammaproteobacteria. It can degrade high molecular mass polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of 4 and 5 rings. The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the type strain CEE_131(T) proved to be distantly related to those of Rheinheimera and Serratia.