Epidemics

In epidemiology, an epidemic occurs when new cases of a certain disease, in a given human population, and during a given period, substantially exceed what is expected based on recent experience. Epidemiologists often consider the term outbreak to be synonymous to epidemic, but the general public typically perceives outbreaks to be more local and less serious than epidemics.

CAUSES

Epidemics of infectious disease are generally caused by a change in the ecology of the host population (e.g. increased stress or increase in the density of a vector species), a genetic change in the parasite population or the introduction of a new parasite to a host population (by movement of parasites or hosts). Generally, an epidemic occurs when host immunity to a parasite population is suddenly reduced below that found in the endemic equilibrium and the transmission threshold is exceeded.

EPIDEMIC VS. PANDEMIC

An epidemic may be restricted to one location; however, if it spreads to other countries or continents and affects a substantial number of people, it may be termed a pandemic. The declaration of an epidemic usually requires a good understanding of a baseline rate of incidence; epidemics for certain diseases, such as influenza, are defined as reaching some defined increase in incidence above this baseline. A few cases of a very rare disease may be classified as an epidemic, while many cases of a common disease (such as the common cold) would not.

INFLUENZA EPIDEMICS

Influenza is an infectious disease of birds and mammals caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae, the influenza viruses . The most common symptoms are chills, fever, sore throat, muscle pains, headache (often severe), coughing, weakness/fatigue and general discomfort. Although it is often confused with other influenza-like illnesses, especially the common cold, influenza is a more severe disease caused by a different type of virus. Influenza may produce nausea and vomiting, particularly in children, but these symptoms are more common in the unrelated gastroenteritis, which is sometimes inaccurately referred to as "stomach flu" or "24-hour flu".

Influenza

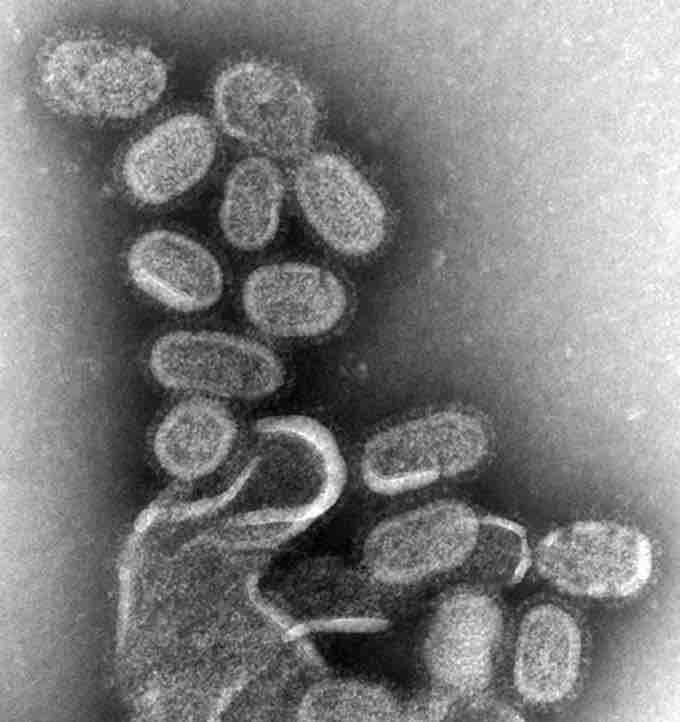

TEM of negatively stained influenza virions, magnified approximately 100,000 times. Modern transport contributes in spreading diseases faster.

Typically, influenza is transmitted through the air by coughs or sneezes, creating aerosols containing the virus. Influenza can also be transmitted by direct contact with bird droppings or nasal secretions, or through contact with contaminated surfaces. Airborne aerosols have been thought to cause most infections, although which means of transmission is most important is not absolutely clear. Influenza viruses can be inactivated by sunlight, disinfectants and detergents. As the virus can be inactivated by soap, frequent hand washing reduces the risk of infection.

Influenza spreads around the world in seasonal epidemics, resulting in about three to five million yearly cases of severe illness and about 250,000 to 500,000 yearly deaths, rising to millions in some pandemic years.

In the 20th century three influenza pandemics occurred, each caused by the appearance of a new strain of the virus in humans, and killed tens of millions of people. Often, new influenza strains appear when an existing flu virus spreads to humans from another animal species, or when an existing human strain picks up new genes from a virus that usually infects birds or pigs. An avian strain named H5N1 raised the concern of a new influenza pandemic after it emerged in Asia in the 1990s, but it has not evolved to a form that spreads easily between people.

In April 2009 a novel flu strain evolved that combined genes from human, pig, and bird flu. Initially dubbed "swine flu" and also known as influenza A/H1N1, it emerged in Mexico, the United States, and several other nations. The World Health Organization officially declared the outbreak to be a pandemic level 6 on 11 June 2009. However, the WHO's declaration of a pandemic level 6 was an indication of spread, not severity; the strain actually having a lower mortality rate than common flu outbreaks.

VACCINATIONS

Vaccinations against influenza are usually made available to people in developed countries. Farmed poultry is often vaccinated to avoid decimation of the flocks. The most common human vaccine is the trivalent influenza vaccine (TIV) that contains purified and inactivated antigens against three viral strains. Typically, this vaccine includes material from two influenza A virus subtypes and one influenza B virus strain. The TIV carries no risk of transmitting the disease, and it has very low reactivity. A vaccine formulated for one year may be ineffective in the following year, since the influenza virus evolves rapidly, and new strains quickly replace the older ones.

Antiviral drugs such as the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir (Tamiflu) have been used to treat influenza; however, their effectiveness is difficult to determine due to much of the data remaining unpublished.