The Ottonians

The Ottonian Renaissance (circa 951-1024) coincided with a period of reform and growth in the church, providing an impetus for the production of religious art. One of the most important art forms of the period was the illuminated manuscript, a manuscript in which the text is supplemented by ornamentation in the form of colored initials, decorative borders, and miniature illustrations, sometimes executed with the addition of gold and silver leaf. Ottonian monasteries produced some of the most magnificent medieval illuminated manuscripts, working with the best of equipment and talent under the direct sponsorship of emperors, bishops, and other wealthy patrons.

The manuscripts produced by Ottonian scriptoria (monastic centers for copying texts) provide invaluable documentation both of contemporary, religious, and political customs, and the stylistic preferences of the period. The most richly illuminated manuscripts were used for display and most likely to be liturgical books, including psalters, gospel books, and huge illuminated complete Bibles. These lavish manuscripts sometimes include a dedication portrait commemorating the book's creation, in which the patron is usually depicted presenting the book to the saint of choice. Colored initials, borders, and marginalia also contain miniature portraits and other decorative emblems and motifs. Illuminated manuscripts were enclosed in ornate metal book covers decorated with gems and ivory carvings.

Following late Carolingian styles, presentation portraits of the patrons of manuscripts are very prominent in Ottonian art. Much Ottonian art reflected the dynasty's desire to establish visually a link to the Christian rulers of Late Antiquity, such as Theodoric and Justinian as well as to their Carolingian predecessors, particularly Charlemagne. This goal was accomplished in various ways. For example, the many Ottonian ruler portraits typically include elements, such as province personifications, or representatives of the military and the Church flanking the emperor, with a lengthy imperial iconographical history.

Master of the Reichenau School. Munich Gospels of Otto III (c. 1000)

Roma, Gallia, Germania, and Sclavinia pay homage to Otto III, from the Munich Gospels of Otto III, one of the Liuthar Group.

Among the greatest artists of the Ottonian period was the anonymous Master of the Registrum Gregorii who worked chiefly in Trier in the 970s to 980s. He derived his title from the miniatures in the Registrum Gregorii (a collection of letters by Pope Gregory the Great) and the Codex Egberti, a famous gospel lectionary manuscript, both for Archbishop Egbert of Trier (circa 950-993). However, most of the 51 images in the Codex Egberti, which represented events in the life of Christ, were made by two monks in the Benedictine monastery on the island of Reichenau on Lake Constance. The scriptorium of Reichenau housed a scriptorium and artists' workshop that has a claim to having been the largest and artistically most influential in Europe during the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. It became famous for its style of gospel illustration in liturgical books. Other famous scriptoria of the Ottonian age were found at the monasteries of Corvey, Hildesheim, and Regensburg, and the cathedral cities of Trier and Cologne.

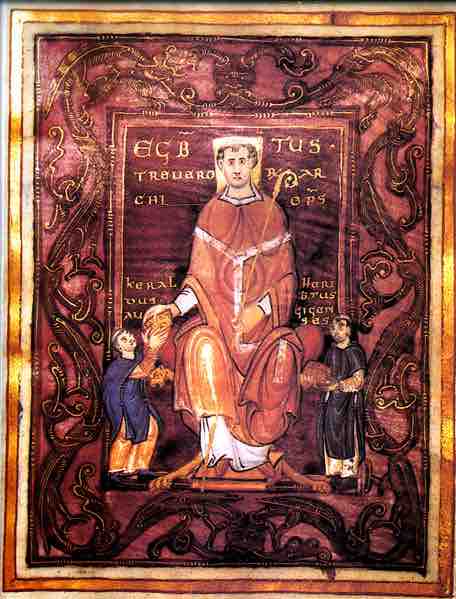

Codex Egberti

The dedicatory page of the Codex Egberti. The portrait is done in purple and gold and says "Egbertus" on top.

The Pericopes of Henry II (1002-1012) is a luxurious medieval illuminated manuscript made for Henry II, the last Ottonian Holy Roman Emperor. The manuscript, which is lavishly illuminated, is a product of the Liuthar Circle of illuminators, who were working in the monastery at Reichenau. The style of the Liuthar Group departs further from rather than returning to classical traditions. Its figures are flattened, stylized, and have exaggerated gestures. Backgrounds are often composed of bands of color with a symbolic rather than naturalistic rationale. As with depictions of Otto II and Otto III, figures' scale is relative to importance, as opposed to based on reality. For example, the Annunciation to the Shepherds depicts the angel as the largest (and thus most important) figure, followed by humans and animals, as was the commonly accepted belief in Christendom at the time. Manuscripts from the Liuthar Group introduced the gold background to Western illumination, a characteristic that would remain common until the Italian Renaissance.

Master of the Reichenau School. Annunciation to the Shepherds

Annunciation to the Shepherds from the Pericopes of Henry II, Liuthar Group of the Reichenau School.