The Source of Inspiration

Romanesque architecture was the first distinctive style to spread across Europe after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Despite the impression of 19th century Art Historians that Romanesque architecture was a continuation of Roman styles, Roman building techniques in brick and stone were largely lost in most parts of Europe. In the more northern countries Roman style and methods had never been adopted except for official buildings, while in Scandinavia they were unknown. There was little continuity, except in Rome where several great Constantinian basilicas continued to stand as an inspiration to later builders. It was not the buildings of ancient Rome that inspired the Emperor Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel,in Aachen, Germany, built around the year AD 800. Instead, the greatest building of the Dark Ages in Europe was the artistic child of the 6th century octagonal Byzantine Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.

A New European Empire

Charlemagne was crowned by the Pope in St. Peter's Basilica on Christmas Day, in the year AD 800, with an aim to re-establishing the old Roman Empire. Charlemagne's political successors continued to rule much of Europe, leading over time to the gradual emergence of the separate political states that were eventually welded into nations, either by allegiance or defeat. In the process the Kingdom of Germany gave rise to the Holy Roman Empire. The invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy, in 1066, saw the building of castles and churches that reinforced the Norman presence. Several significant churches built at this time were founded by rulers as seats of temporal and religious power, or as places of coronation and burial. These include the Abbaye-Saint-Denis and Westminster Abbey (where little of the Norman church now remains).

At a time when the remaining architectural structures of the Roman Empire were falling into decay and much of its technology was lost, the building of masonry domes and the carving of decorative architectural details continued unabated, though greatly evolved in style since the fall of Rome, in the enduring Byzantine Empire. The domed churches of Constantinople and Eastern Europe were to greatly affect the architecture of certain towns, particularly through trade and through the Crusades. The most notable single building that demonstrates this is St Mark's Basilica, Venice but there are many lesser known examples, such as the church of Saint-Front, Périgueux and Angoulême Cathedral.

Church of Saint Front, Perigueux, France

Church of Saint Front, Perigueux, France.

Feudalism and Warfare

Much of Europe was affected by feudalism, in which peasants held tenure from local rulers over the land they farmed in exchange for military service. The result of this was that they could be called upon, not only for local spats, but to follow their lord to travel across Europe to the Crusades. The Crusades, 1095–1270, brought about a very large movement of people, and with them ideas and trade skills, particularly those involved in the building of fortifications and the metal working needed for the provision of arms, which was also applied to the fitting and decoration of buildings . The continual movement of people, rulers, nobles, bishops, abbots, craftsmen and peasants, was an important factor in creating a homogeneity in building methods and a recognizable Romanesque style, despite regional differences.

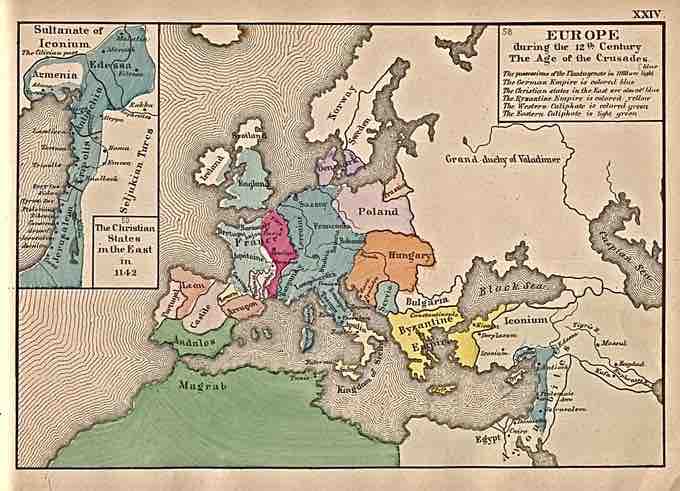

Map of Europe, 1142

Europe, 1142. Age of the Crusages.

Life became generally less secure after the Carolingian period. This resulted in the building of castles at strategic points. Many were constructed as strongholds of the Normans; descendants of the Vikings who invaded northern France in 911. Political struggles also resulted in the fortification of many towns, or the rebuilding and strengthening of walls that remained from the Roman period. One of the most notable surviving fortifications is that of the city of Carcassonne. The enclosure of towns brought about a lack of living space within the walls, and resulted in a style of town house that was tall and narrow, often surrounding communal courtyards, as at San Gimignano in Tuscany .

San Gimignano, Italy

San Gimignano, Italy. Famous for its medieval architecture, unique in the preservation of about a dozen of its tower houses.

Growing Prosperity

The period saw Europe grow steadily more prosperous, and art of the highest quality was no longer confined to the royal court and a small circle of monasteries, as it largely had been in the Carolingian and Ottonian periods. Monasteries remained extremely important, especially those of the expansionist new Cistercian, Cluniac, and Carthusian orders of the period that spread out across Europe. However, city churches, including those on pilgrimage routes and many churches in small towns and villages, were elaborately decorated to a very high standard. Indeed, it is often these that have survived when cathedrals and city churches have been rebuilt, and no Romanesque royal palace has really survived.The lay artist was becoming a valued figure; Nicholas of Verdun seems to have been known across the continent. Most masons and goldsmiths were now lay professionals rather than monastic clergy, and lay painters like Master Hugo seem to have been the majority, at least of those doing the best work, by the end of the period. The iconography of their church work was likely arrived at in consultation with clerical advisers.