Originally a ducal family from Saxony, the Ottonians (named after their first king Otto I the Great) seized power after the collapse of Carolingian rule in Europe and re-established the Holy Roman Empire. Ottonian architecture first developed during the reign of Otto the Great (936 - 975 C.E.) and lasted until the mid-eleventh century. Surviving examples of this style of architecture are found today in Germany and Belgium.

Ottonian architecture chiefly drew its inspiration from both Carolingian and Byzantine architecture and represents the absorption of classical Mediterranean and Christian architectural forms with Germanic styles. In some of its features, it foreshadows the development of Romanesque architecture which emerged in the mid-eleventh century. It is remarkable for its balance and mathematical harmony--a true reflection of the high regard in which the Ottonians held the mathematical sciences. This mathematical harmony often surfaces in the modular planning, which base the measurements of each component of the church's interior is based on a single square unit and either multiplied or divided accordingly.

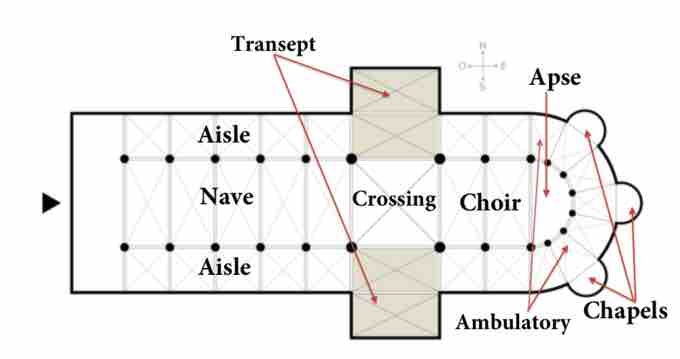

Barring a few examples that were influenced by the octagonal Palatine Chapel built by Charlemagne in Aachen, Ottonian religious architecture tends to diverge from the model of the central-plan church, drawing inspiration instead from the Roman (Western) basilica, which typically consisted of a long central nave with an aisle at each side and an apse at one end. When adopted by early Christians, the basilica plan assumed a transept, which runs perpendicular to the nave, forming a cruciform shape to commemorate the Crucifixion.

Plan of a typical Western basilican church

The arrow at the left marks the entrance to the church. Main seating for worshipers is located in the nave, while the aisles were originally used to accommodate large crowds on feast days. As churches began collecting relics (housed in the chapels), which attracted pilgrims, churches added the ambulatory, which connects the aisles to the chapels behind the choir, where clergy members perform their rituals.

The Ottonians adopted the Carolingian double-ended variation on the Roman basilica, featuring apses at the east and west ends of the church rather than merely facing east. Most Ottonian churches make generous use of the round arch, have flat ceilings, and insert massive rectangular piers between columns in regular patterns, as is seen in St. Cyriakus at Gernrode and St. Michael's at Hildesheim.

Plan of St. Cyriakus at Gernrode.

This plan shows the apse at both the west and east ends of the church, with a single transept dividing the nave from the east apse. The black circles and rectangles between the nave and each aisle mark the alternating columns (circles) and piers (rectangles).

One of the finest surviving examples of Ottonian architecture is St. Cyriakus Church (960-965) in Gernrode, Germany. The central body of the church has the nave with two aisles flanked by two towers characteristic of Carolingian architecture. However, it also displays novelties anticipating Romanesque architecture, including the alternation of pillars and columns (a common feature in later Saxon churches), semi-blind arcades in galleries on the nave, and column capitals decorated with stylized acanthus leaves and human heads.

Church of St. Cyriakus, Gernrode

St. Cyriakus is one of the few surviving examples of Ottonian architecture and combines Carolingian elements with innovations that anticipate Romanesque architecture.

St. Cyriakus, interior facing west.

St. Michael's at Hildesheim (1010-1031) is one of the most important Ottonian churches. It is a double-choir basilica with two transepts and a square tower at each crossing. This layout can be seen from the exterior of the building. The west choir is emphasized by an ambulatory and a crypt. Adhering to the Ottonian appreciation for mathematics, the ground plan of the building follows a geometrical conception in which the square of the transept crossing in the ground plan constitutes the key measuring unit for the entire church. The square units are defined by the alternation of columns and piers. Unlike St. Cyriakus, St. Michael's lacks a second-story gallery. However, ample light enters through a row of clerestory windows placed above the arcades dividing the name from the aisles.

St. Michael's Church at Hildesheim (1010-1031).

Unlike the Romanesque churches that would follow, Ottonian churches like St. Michael's had two apses (visible at the right and left ends of this photograph) and two transepts that divided each apse from the central nave area.

St. Michael's at Hildesheim, interior facing east.

Major differences between St. Michael's and St. Cyriakus are the clerestory windows in place of galleries and one pier placed after each pair of columns. The round arches at the east end of the divide the nave from the crossing and the crossing from the apse.