Following the Allied victory, President Woodrow Wilson met with his counterparts, Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Great Britain and Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau of France, at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. These leaders largely set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers, reshaping the map of Europe through territorial expansions and losses that favored the victors. While the conference should have been considered a victory for Wilson, whose envisioned League of Nations was established, the U.S. Congress refused to accept the terms of the conference’s cornerstone work, the Treaty of Versailles.

Negotiating the Peace

Germany and Communist Russia were not invited to attend negotiations at the conference, but numerous other nations sent delegations, each with a different agenda. For six months, Paris was effectively the center of a world government as the peacemakers dealt with bankrupt empires and created new countries.

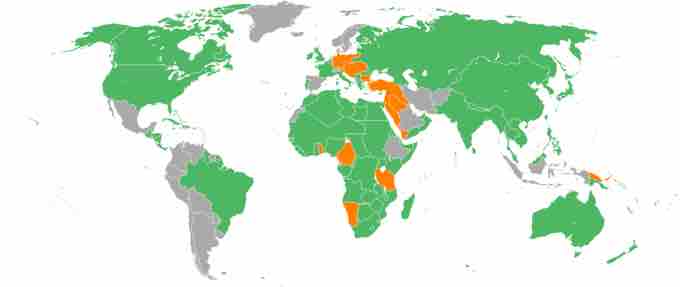

Participant Countries in World War I

Map of the world with the participants in World War I. The Allies are depicted in green, the Central Powers in orange, and neutral countries in grey. World War I involved most the world, and subsequently peace negotiations did as well.

The most contentious outcome of the Paris Peace Conference was a punitive peace accord, the Treaty of Versailles, which included a “war-guilt clause” laying blame for the outbreak of war on Germany and, as punishment, weakening its military and required it to pay all war costs of the victorious nations. Also as a result of the conference’s post-war settlements, the Austro-Hungarian Empire ceased to exist and new, self-governing states were created for its disparate ethnic peoples.

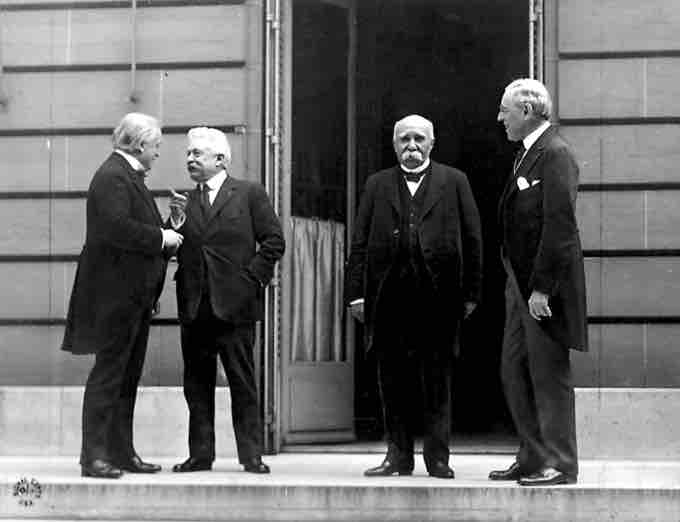

Paris Peace Conference Negotiators

Allied leaders during the Paris Peace Conference including, from left, Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Britain, Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau of France, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

Failure to Adopt the Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points Wilson proffered in a 1918 speech to the U.S. Congress had helped win the hearts and minds of Americans and Europeans, including Germany and its allies, and his diplomacy essentially established the conditions for the armistices that brought the war to an end. No American president had ever visited Europe while in office, but Wilson believed it was his duty to be a prominent figure at the peace negotiations, with high hopes and expectations placed on him to deliver what he had promised for the post-war era. In doing so, Wilson was ultimately leading U.S. foreign policy toward interventionism, a move strongly resisted in some domestic circles.

Upon his arrival at the conference, Wilson worked to influence the direction that the French delegation led by Clemenceau and the British under Lloyd George took toward Germany and its fallen allies, as well as the former Ottoman lands in the Middle East. Yet Wilson's attempts to gain acceptance of his Fourteen Points ultimately failed after France and Britain refused to adopt some specific points and its core principles, although they tried to appease the American president by consenting to the establishment of his League of Nations. Several of the Fourteen Points conflicted with other European powers, as well.

The United States did not believe responsibility for the war or the war-guilt clause placed on Germany was fair or warranted. It would not be until 1921, under President Warren Harding, that the United States finally signed separate peace treaties with Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

United States Rejects Treaty

The Republican Party, led by Henry Cabot Lodge, controlled the U.S. Senate after the election of 1918, but its members were divided into multiple positions on the Versailles question. It proved possible to build a majority coalition, but they could not attain the two-thirds majority needed to pass the treaty. Among the American public, Irish-Catholics and German-Americans were intensely opposed to the treaty, claiming it favored the British.

An angry bloc in the Senate of 12 to 18 "Irreconcilables" – mostly Republicans, but also representatives of the Irish and German Democrats – fiercely opposed the treaty. One bloc of Democrats strongly supported the Versailles Treaty, even with reservations added by Lodge. A second group of Democrats supported the treaty but followed Wilson in opposing any amendments or reservations. The largest bloc, led Lodge, comprised a majority of the Republicans who wanted a treaty with reservations, especially on Article X, which involved the power of the League of Nations to make war without a vote by the U.S. Congress. All of the Irreconcilables were bitter enemies of President Wilson, and he launched a nationwide speaking tour in the summer of 1919 to refute them. However, Wilson collapsed midway through the tour with a serious stroke that effectively ruined his leadership skills.

Henry Cabot Lodge

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge led the Irreconcilables, who blocked approval of the Treaty of Versailles in the U.S. Congress.

The closest the treaty came to passage in Congress was on November 19, 1919, as Lodge and his fellow Republicans formed a coalition with pro-treaty Democrats and were close to a two-thirds majority for a treaty with reservations. Wilson rejected this compromise, however, and enough Democrats followed his lead to permanently end chances for ratification. During this period, Wilson became less trustful of the press and stopped holding press conferences, preferring to use his propaganda unit, the Committee for Public Information. A poll of historians in 2006 cited Wilson's failure to compromise with the Republicans on U.S. entry into the league as one of the 10 biggest errors by an American president.

Wilson's successor, President Warren G. Harding, continued American opposition to the League of Nations. It was not until July 21, 1921, that Harding signed into law the Knox-Porter Resolution drafted by Congress, which formally ended hostilities between the U.S. and the Central Powers.

Post-WWI Territorial Changes

The Treaty of Versailles included a number of territorial changes including Germany’s forced return of territories in Europe and yield of control over its colonies. The province of West Prussia was ceded to the restored Poland, granting it access to the Baltic Sea and turning East Prussia into an exclave separated from mainland Germany.

The major territorial changes included:

- After approximately 200 years of French rule, Alsace and the German-speaking part of Lorraine were ceded to Germany in 1871. In 1919, these regions returned to France.

- Most Prussian provinces were ceded to Poland.

- New territories were transferred to Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Belgium.

- Germany lost Kaliningrad, a strategically important port on the Baltic Sea.

- Austria was forbidden from integrating with or into Germany.

- German colonies were divided between Belgium, Great Britain and certain British Dominions, France, and Japan.

- In Africa, Britain and France divided German Kamerun (Cameroons) and Togoland. Belgium and the U.K. gained territory in German East Africa, and Portugal received a sliver of German East Africa. German South West Africa was mandated to the Union of South Africa.

- In the Pacific, Japan gained Germany's islands north of the equator (the Marshall Islands, the Carolines, the Marianas, and the Palau Islands) and Kiautschou in China. German Samoa was assigned to New Zealand while German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Nauru were assigned to Australia.

Negotiations in the Middle East

In the Middle East, negotiations were complicated by competing aims, claims, and the new mandate system. The United States hoped to establish a more liberal and diplomatic world, as stated in the Fourteen Points, where democracy, sovereignty, liberty, and self-determination would be respected. France and Britain, on the other hand, already controlled empires, wielded power over subjects around the world, and aspired to be dominant colonial powers.

In light of the previously secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, a 1916 treaty regarding European spheres of influence in the regions, and following the adoption of the mandate system on the Arab province of the former Ottoman lands, the conference heard statements from competing Zionist and Arab claimants. President Wilson recommended an international commission of inquiry to ascertain the wishes of the local inhabitants. Eventually it became the purely American King-Crane Commission, an investigatory commission that toured all of Syria and Palestine during the summer of 1919, taking statements and sampling opinion. Its report, presented to President Wilson, was kept secret from the public until The New York Times broke the story in December 1922, although a pro-Zionist joint resolution on Palestine was passed by Congress in September 1922.