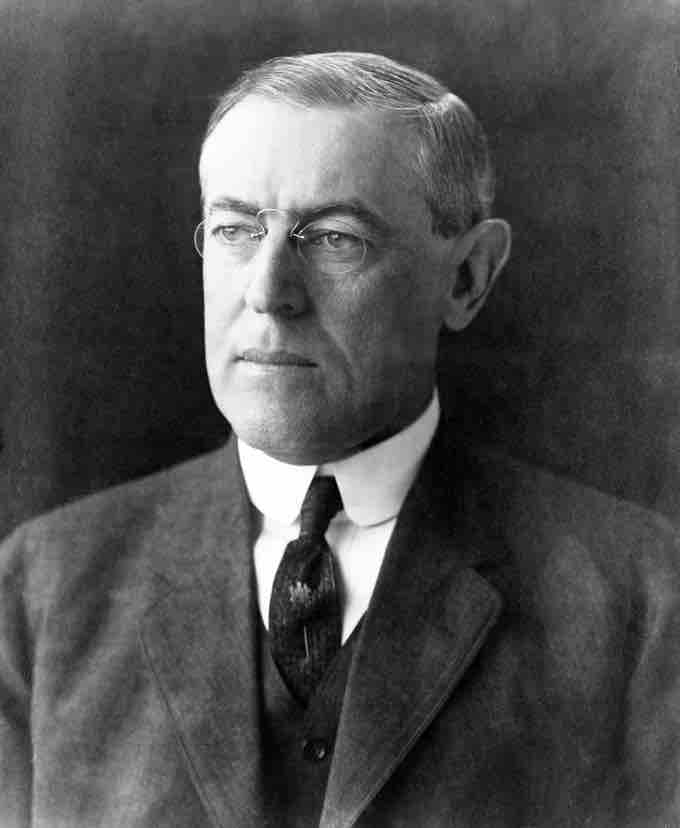

The Fourteen Points was a speech given by United States President Woodrow Wilson to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918. The address was intended to assure the country that World War I, which America had joined on April 6, 1917, was being fought for a moral cause and for a lasting, postwar peace in Europe.

Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points speech outlined his goals for postwar cooperation.

The speech was delivered 10 months before the armistice with Germany in November 1918 and became the basis for the terms of the German surrender, as negotiated at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his peace-making efforts first envisioned in the speech.

Content of the Speech

Some belligerents in the conflict gave general indications of their aims but most kept their postwar goals to themselves, making the Fourteen Points speech the only explicit statement of war aims by any of the nations fighting in World War I.

Each of the Fourteen Points detailed in the speech were based on research by a team of about 150 experts, led by Wilson’s foreign policy advisor, Edward M. House, on the topics most likely to arise in the anticipated peace conference at the end of the war. Wilson's speech translated many of the principles of Progressivism that had produced domestic reform in the U.S. into foreign policy objectives for all nations, including free trade, open agreements, democracy, and self-determination.

The speech also addressed goals articulated in Vladimir Lenin's Decree on Peace of October 1917, including a just and democratic peace uncompromised by territorial annexations. The decree led to the March 3, 1918, signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, under which Russia immediately withdrew from the war.

The Fourteen Points could be simplified to a core list of agreements and goals for all participating nations:

- No secret alliances between countries.

- Freedom of the seas in peace and war.

- Reduced trade barriers among nations.

- General reduction of armaments.

- Adjustment of colonial claims in the interests of inhabitants as well as the colonial powers.

- Evacuation of Russian territory and a welcome for its government to the society of nations.

- Restoration of Belgian territories in Germany.

- Evacuation of all French territory, including Alsace-Lorraine.

- Readjustment of Italian boundaries along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

- Independence for various national groups in Austria-Hungary.

- Restoration of the Balkan nations and free access to the sea for Serbia.

- Protection for minorities in Turkey and the free passage of the ships of all nations through the Dardanelles.

- Independence for Poland, including access to the sea.

- Establishment of a League of Nations to protect "mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small nations alike."

International Reaction

The speech was widely disseminated as an instrument of propaganda to encourage the Allies to victory. Copies were dropped behind German lines to encourage the Central Powers to surrender in the expectation of a just settlement and, indeed, that was the result – a note sent to Wilson by German Imperial Chancellor Maximilian of Baden in October 1918 requested an immediate armistice and peace negotiations on the basis of the Fourteen Points.

The speech was made without prior coordination or consultation with Wilson's counterparts in Europe and was the only public statement of war aims made by any of the combatants. This made it the centerpiece of the long debates over an equitable peace settlement and treaty terms that came afterward.

Fourteen Points vs. Treaty of Versailles

The Fourteen Points were accepted by France and Italy on November 1, 1918. Britain later signed off on all of the points except the freedom of the seas. The United Kingdom also wanted Germany to make reparation payments for the war and believed that condition should be included in the Fourteen Points.

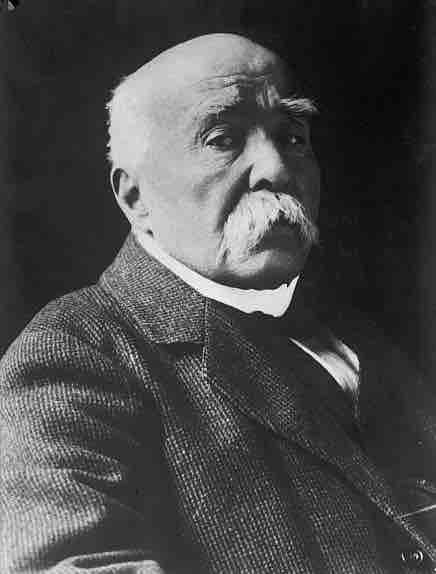

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Clemenceau (28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) served as the Prime Minister of France and was one of the principal architects of the Treaty of Versailles.

President Wilson became sick at the onset of the Paris Peace Conference, which began on January 18, 1919 at the Palace of Versailles approximately 12 miles from Paris. Wilson’s illness enabled the right-wing French Chancellor Georges Clemenceau to lead the other two members of the “Big Four” powers – British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando – in changing many aspects of Wilson's plan.

The most controversial alteration was that Germany received the blame for the whole war and was required to pay an astronomical sum in war reparations, including compensation for the damage inflicted on the territories its military occupied and funding for the pensions of wounded Allied soldiers and widows. Germany was also denied an air force, and the German army was not to exceed 100,000 men.

Big Four of World War I

The leaders of the "Big Four" Allied powers at the Paris Peace Conference, May 27, 1919. From left to right, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

The difference between President Wilson's comparably honorable peace offer toward the German Empire, which was far less harsh than the demanded break up the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the terms laid out in the final version of the Treaty of Versailles led to great anger in Germany. The treaty came to be known there as “the stab in the back,” a major propaganda slogan used in the years that followed by embittered German nationalists and ultimately the Nazi Party. The Treaty of Versailles had little to do with the Fourteen Points and was never ratified by the U.S. Senate