Support for America’s entry into World War I was not unanimous. A number of groups on the home front opposed joining the conflict in Europe for different reasons, most of which could be traced to their political or religious beliefs. Among these dissenters, some of the loudest protests came from so-called Old-Stock Americans, as well as Americans of Irish descent.

Old-Stock Americans

The dominant voice in American politics at the time of World War I was that of Old-Stock Americans, who were white and primarily Protestant Christians. Old-Stock moralism was aggressively focused on banishing from the face of the Earth things they perceived to be sources of evil, primarily saloons, through acts such as Prohibition, a legal ban on selling and consuming alcohol. The largest Protestant denominations among these, including Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, Disciples of Christ, Congregational, and some Lutheran groups, loudly denounced the war at first, arguing that it was God's punishment for sin.

Come on in, America, the Blood's Fine! by M.A. Kempf

This antiwar cartoon published in June 1917 depicts three women (England, France, and Germany) being embraced by War in a sea of blood and corpses. Antiwar sentiment was still strong in the U.S., despite growing calls for an end to neutrality.

The intensely religious son of a prominent theologian, Wilson had established himself as a believer in the role of Christian morality in public affairs. “America was born a Christian nation,” he stated in a 1911 speech. “America was born to exemplify that devotion to the elements of righteousness which derived from the revelations of Holy Scripture.” Wilson, therefore, knew religion could be utilized in American foreign policy and that by showing German militarism to be morally evil, the Old Stock would throw enormous weight behind the war effort. He harnessed this moralism with verbal attacks on the "Huns" – a derogatory term for Germans – whom he said threatened civilization, and through his calls for an almost religious crusade for peace. In his April 2, 1917 address to Congress requesting a declaration of war against Germany, Wilson ends by saying, “America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.”

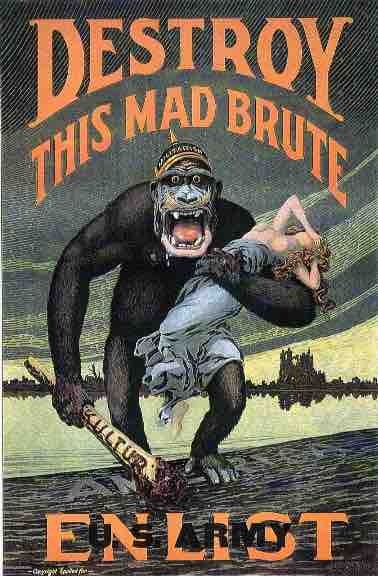

"Destroy this mad brute! "

Some characterizations of the Germans as "Huns" were racist and manipulative, but were an attempt to persuade Americans that the war against Germany was moral.

Irish-Americans

The most effective domestic opponents of the war were Irish-American Catholics, who had little interest in mainland Europe, but were adamantly opposed to aiding the British Empire because of its long-standing refusal to grant independence to Ireland. The April 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin was crushed within a week by the occupying British military government and the Irish Republican leaders subsequently executed by firing squad. This series of events resonated deeply with Irish-Americans, who dominated the Democratic Party in many large cities.

Irish-Americans did not prevent the president from being hostile to Germany, but forced the U.S. government to maintain a polite diplomatic distance from Britain and define its own war objectives, primarily restructuring the post-war world in Liberal Democratic fashion. This stance of not completely siding with British interests gave the Irish-American community reason to believe it had an implicit promise from Wilson to promote Irish independence in exchange for their support of his war policies.

Therefore, the Irish-Americans were bitterly disappointed by Wilson’s refusal after his reelection to support them or the movement for Irish independence. Despite Wilson’s habit of telling big city audiences of his Irish ancestry through two paternal grandparents from County Tyrone, and making references to “the great Irish people” during his first presidential campaign, they realized, too late, that the president had only curried their favor for fear of losing the votes of such an important constituency within his own party.

In fact, Wilson never held America’s Irish community in any high regard. Presidential adviser Colonel Edward M. House wrote in his personal diary in 1918, “In speaking of the Irish he surprised me by saying that he did not intend to appoint another Irishman to anything; that they were untrustworthy and uncertain. He thought Tumulty [Wilson’s private secretary, Joseph Patrick Tumulty] was the only one he had come into contact with who was.”