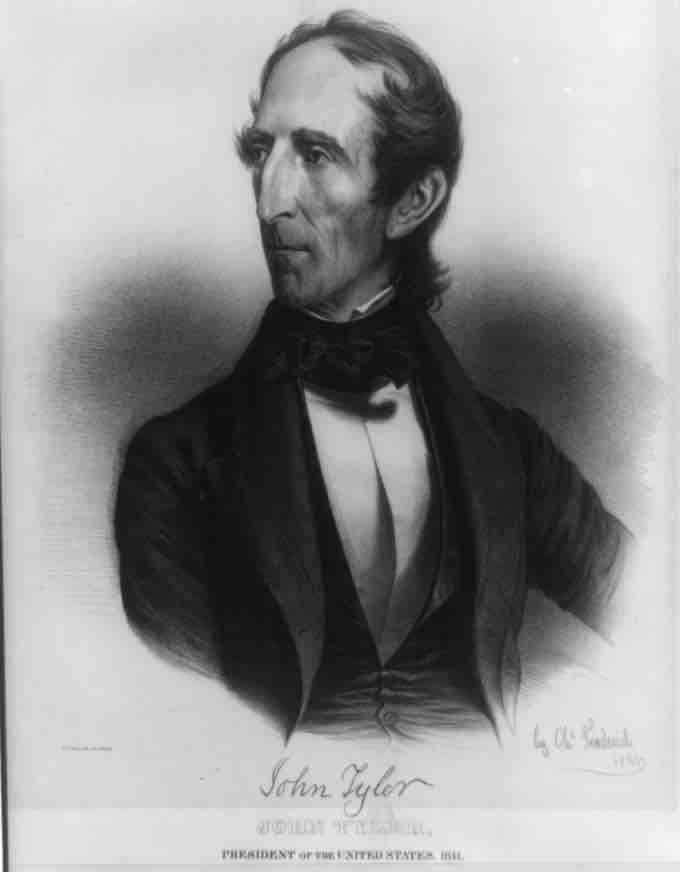

President John Tyler

While John Tyler had a difficult time with domestic policy during his presidency (1841–1845), he oversaw many accomplishments in foreign policy, especially in the areas of westward expansion. He had long been an advocate of expansion toward the Pacific, and of free trade, and was fond of evoking themes of national destiny and the spread of liberty in support of these policies. His presidency continued Andrew Jackson's earlier efforts to promote US commerce across the Pacific. He applied the Monroe Doctrine to Hawaii, told Britain not to interfere there, and began the process toward eventual US annexation of Hawaii. In 1842, Secretary of State Daniel Webster negotiated the Webster–Ashburton Treaty with Britain, which concluded where the border between Maine and Canada lay. However, Tyler was unsuccessful in concluding a treaty with the British to fix Oregon's boundaries. On Tyler's last full day in office, March 3, 1845, Florida was admitted to the Union as the 27th state.

Americans at this time asserted a right to colonize vast expanses of North America beyond their country's borders, especially in Oregon, California, and Texas. By the mid-1840s, US expansionism was articulated in the ideology of manifest destiny. Major events in the western movement of the US population were the Homestead Act, a law by which, for a nominal price, a settler was given a title to 160 acres of land to farm. Other significant events included the opening of the Oregon Trail, the Mormon Emigration to Utah in 1846–'47, the California Gold Rush of 1849, the Colorado Gold Rush of 1859, and the completion of the nation's First Transcontinental Railroad on May 10, 1869.

The Issue of Texas

Following the slaveholder Tyler's break with the Whigs in 1841, he had begun to shift back to his old Democratic party. However, its members were not ready to receive him. He knew that with little chance of re-election, the only way to salvage his presidency and legacy was to move public opinion in favor of the Texas issue, and he formed his own political party to lobby the Democratic Party in favor of annexation.

Tyler supporters with signs reading "Tyler and Texas!" held their nominating convention in Baltimore in May 1844, just as the Democratic Party was also nominating its presidential candidate. With their high visibility and energy, they were able to force the Democrats' hand in favor of annexation. Ballot after ballot, Democratic candidate Martin Van Buren failed to win the necessary super-majority of Democratic votes and slowly fell in the ranking. It was not until the ninth ballot that the Democrats discovered an obscure pro-annexation candidate named James K. Polk. They found him to be perfectly suited for their platform, and he was nominated with two-thirds of the vote. Tyler considered his work vindicated and implied in an acceptance letter that annexation was his true priority, rather than re-election.

President Tyler entered negotiations with the Republic of Texas for an annexation treaty, which he submitted to the Senate. On June 8, 1844, the treaty was defeated 35 to 16, well below the two-thirds majority necessary for ratification. Of the 29 Whig senators, 28 voted against the treaty with only one Whig, a southerner, supporting it. The Democratic senators were more divided on the issue; in the north, six opposed while five supported the treaty, while one opposed and 10 supported it in the south.

Election of 1844

Tyler was unfazed, however, and he felt annexation was now within reach. He called for Congress to annex Texas by joint resolution rather than by treaty. Former President Jackson, a staunch supporter of annexation, persuaded presidential candidate Polk to welcome Tyler back into the Democratic party, and ordered Democratic editors to cease their attacks on the him. Satisfied by these developments, Tyler dropped out of the presidential race in August and endorsed Polk for the presidency. Polk's narrow victory over Clay in the November election was seen by the Tyler administration as a mandate for completing the resolution.

Annexation

After the election, the Tyler administration consulted with President-elect Polk and set out to accomplish annexation via a joint resolution. The resolution declared that Texas would be admitted as a state as long as it approved annexation by January 1, 1846, that it could split itself into four additional states, and that possession of the Republic's public land would shift to the state of Texas upon its admission. On February 26, 1845, 6 days before Polk took office, Congress passed the joint resolution, and Tyler signed the bill into law on March 1, just 3 days before the end of his term.

On July 4, 1845, the Texan Congress endorsed the American annexation offer with only one dissenting vote, and began writing a state constitution. The citizens of Texas approved the new constitution and the annexation ordinance on October 13, 1845, and President Polk signed the documents formally integrating Texas into the United States on December 29, 1845.

Texas and Mexico Border

Prior to annexation there was an ongoing border dispute between the Republic of Texas and Mexico. Texas claimed the Rio Grande as its border, while Mexico maintained it was the Nueces River, and did not recognize Texan independence. President Polk ordered General Zachary Taylor to garrison the southern border of Texas, as defined by the former Republic. Taylor moved into Texas, ignoring Mexican demands to withdraw. Indeed, Taylor marched as far south as the Rio Grande, where he began to build a fort near the river's mouth on the Gulf of Mexico. The Mexican government regarded this action as a violation of its sovereignty.

The Republic of Texas never controlled what is now New Mexico, and the failed Texas Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 was its only attempt to take that territory. El Paso was only taken under Texas governance by Robert Neighbors in 1850, over 4 years after annexation. Neighbors was not welcomed in New Mexico. Texas continued to claim New Mexico as far as the Rio Grande, supported by the rest of the South and opposed by the North and by New Mexico itself. The Texas/New Mexico boundary was not established until the Compromise of 1850.

John Tyler, c. 1841

John Tyler endorsed the idea of manifest destiny to defend the continued expansion of the United States, including the annexation of Texas.