Diversity in Foreign Policy

The foreign policies of the John F. Kennedy administration in 1961–1963 saw both diplomatic and military initiatives in Europe, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and other regions amid considerable Cold War tensions. To counter Soviet influence in the developing world (a policy known as containment), Kennedy supported a variety of measures in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa.

During his presidency, Kennedy established the Agency for International Development to oversee the distribution of foreign aid. He also founded the Peace Corps, which recruited idealistic young people to undertake humanitarian projects in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. He hoped that by augmenting the food supply and improving healthcare and education, the U.S. government could encourage developing nations to align themselves with the United States and reject Soviet or Chinese overtures and the spread of communism. The first group of Peace Corps volunteers departed for the four corners of the globe in 1961, serving as an instrument of “soft power” in the Cold War.

Foreign Policy in Latin America: The Alliance for Progress

Kennedy's most well known act regarding Latin America was the Alliance for Progress, which aimed to establish economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America. In March of 1961, Kennedy proposed a ten-year plan for Latin America, which called for an annual increase of 2.5% in per capita income; the establishment of democratic governments; the elimination of adult illiteracy by 1970; price stability to avoid inflation or deflation; more equitable income distribution; land reform; and economic and social planning.

Economic assistance to Latin America nearly tripled between fiscal years 1960 and 1961. Between 1962 and 1967, the U.S. supplied $1.4 billion per year to Latin America. However, Latin American countries still had to pay off their increasing debt to the U.S. and other first-world countries, limiting their financial independence.

The Alliance for Progress achieved a short-lived public relations success. It also had real but limited economic advances. However, by the early 1970s, the program was widely viewed as a failure. Like all economic development programs, it was rife with complications. It is often argued that the program failed for three reasons: (1) not all Latin American nations were willing to enact the exact reforms the U.S. demanded in exchange for their assistance; (2) presidents after Kennedy were less supportive of the program; and (3) the amount of money was not enough for an entire hemisphere - $20 billion averaged out to only $10 per person in Latin America.

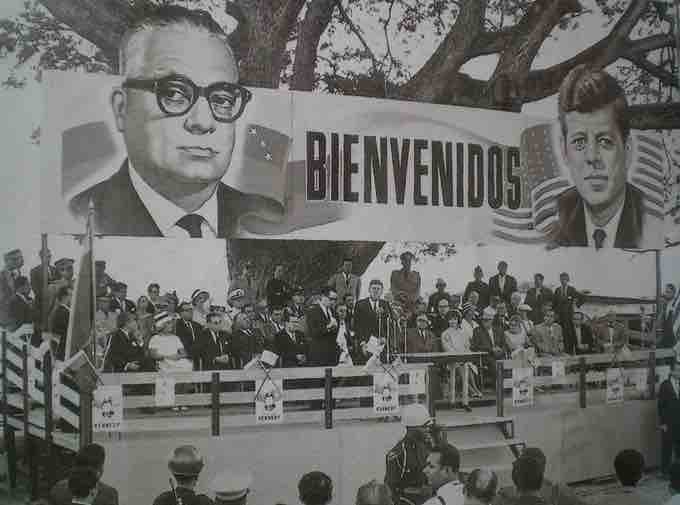

Alliance for Progress

Venezuelan President Rómulo Betancourt and U.S. President John F. Kennedy at La Morita, Venezuela, during an official meeting for the Alliance for Progress in 1961.

Foreign Policy in the Middle East

Kennedy firmly believed in the U.S. commitment to Israeli security, and he recognized the ambitious Pan-Arabic initiatives of Egypt's leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser. In the summer of 1960, the U.S. embassy in Tel-Aviv, Israel, learned that France was helping Israel construct "a significant atomic installation." Although Israel's Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion had publicly assured the United States that Israel did not plan to develop nuclear weapons, Kennedy tried to persuade Israel to permit some qualified expert to visit the site.

Kennedy wished to work more closely with the modernizing forces of the Arab world. In June of 1962, Nasser wrote Kennedy a letter, noting that though Egypt and the United States had their differences, they could still cooperate. Around this time, civil war broke out in North Yemen. Fearing it would lead to a larger conflict between Egypt and Saudi Arabia (which might involve the United States as an ally of Saudi Arabia), Kennedy decided to recognize the revolutionary regime, hoping it could stabilize the situation in Yemen. Kennedy continued to try to persuade Nasser to pull out his troops.

Foreign Policy in Africa

Kennedy's approach to African affairs contrasted sharply with that of his predecessor. By naming young appointees, including scholars and liberal Democrats with government experience, to several embassies, Kennedy broke with Eisenhower's pattern. Under Kennedy, a civil rights activist was tasked with management of the African affairs. According to Nigerian diplomat Samuel Ibe, "with Kennedy there were sparks"; the Prime Minister of Sudan Ibrahim Abboud, cherishing a hunting rifle Kennedy gave him, expressed the wish to go on safari with Kennedy.

JFK and Africa

John and Jackie Kennedy, along with Côte d'Ivoire President Félix Houphouët-Boigny and his wife, at a state dinner in the White House, 1962.

The Kennedy administration believed that the British African colonies would soon achieve independence through what the Kennedy team termed middle-class revolution; they further believed the countries would grow to economic and political maturity. By the spring of 1962, American aid made its way to Guinea. On his return from Washington, leader of Guinea Ahmed Sékou Touré reported to his people that he and Guinean delegation found in Kennedy "a man quite open to African problems and determined to promote the American contribution to their happy solution." Touré also expressed his satisfaction about the "firmness with which the United States struggles against racial discrimination."

Kennedy gave a speech at Saint Anselm College on May 5, 1960, regarding America's conduct in the emerging Cold War. The address detailed how American foreign policy should be conducted toward African nations, noting a hint of support for modern African nationalism by saying that "For we, too, founded a new nation on revolt from colonial rule."