Background: The Cold War

The spread of communism during the Kennedy administration represented a perceived threat to the power and dominance of the Western world. Thus, a leading premise during the Kennedy years was the need to contain communism at any cost. Kennedy felt that the spread of communism (what became known as the "hour of maximum danger") required the policy of containment.

In his Inaugural Address on January 20, 1961, Kennedy presented the American public with a blueprint upon which the future foreign policy initiatives of his administration would later follow and come to represent. In this Address, Kennedy warned "Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty." He also called upon the public to assist in "a struggle against the common enemies of man: tyranny, poverty, disease, and war itself."

Some of the most notable policies that stemmed from tenets of Kennedy's initiatives to contain communism were the Kennedy Doctrine and Alliance for Progress in Latin America and increased involvement in Vietnam. Amidst this backdrop, the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded in 1962.

Castro and the Bay of Pigs

In January of 1959, following the overthrow of the corrupt and dictatorial regime of Fulgencio Batista, Castro assumed leadership of the new Cuban government. The progressive reforms he began indicated that he favored communism, and his pro-Soviet foreign policy frightened the current Eisenhower administration in the U.S., which asked the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to find a way to remove him from power. Rather than have the U.S. military invade the small island nation, less than one hundred miles from Florida, and risk the world’s criticism, the CIA instead trained a small force of Cuban exiles for the job. After landing at the Bay of Pigs on the Cuban coast, these insurgents, the CIA believed, would inspire their countrymen to rise up and topple Castro’s regime. The United States also promised air support for the invasion.

Kennedy agreed to support the previous administration’s plans, and on April 17, 1961, approximately 1,400 Cuban exiles stormed ashore at the designated spot. However, Kennedy feared domestic criticism and worried about Soviet retaliation elsewhere in the world, such as Berlin. He cancelled the anticipated air support, which enabled the Cuban army to easily defeat the insurgents. The hoped-for uprising of the Cuban people also failed to occur. The surviving members of the exile army were taken into custody. The Bay of Pigs invasion was a major foreign policy disaster for President Kennedy and highlighted Cuba’s military vulnerability to the Castro administration.

Crisis in Cuba

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a thirteen-day confrontation between the Soviet Union and Cuba on one side and the United States on the other. The crisis occurred in October of 1962, at the height of the Cold War.

Increasing Weapons

A year after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, the Soviet Union sent troops and technicians to Cuba to strengthen its new ally against further U.S. military plots. Then in August of 1962, the Cuban and Soviet governments secretly began to build bases in Cuba for a number of medium-range and intermediate-range ballistic nuclear missiles that would have the ability to strike most of the continental United States. This action followed the United States' 1958 deployment of intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Italy and Turkey in 1961, which meant that more than 100 U.S.-built missiles had the capability to strike Moscow with nuclear warheads. On October 14, 1962, a United States Air Force U-2 plane on a photo-reconnaissance mission captured photographic proof of Soviet missile bases under construction in Cuba.

Reconnaissance Photos

U-2 reconnaissance photograph of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Missile transports and tents for fueling and maintenance are visible in the photograph.

U.S. Response

The United States considered attacking Cuba via air and sea but decided on a military blockade instead, calling it a "quarantine" rather than a "blockade" for legal and other reasons. The U.S. announced it would not permit offensive weapons to be delivered to Cuba and demanded that the Soviets dismantle the missile bases already under construction or completed in Cuba and remove all offensive weapons. The Kennedy administration held only a slim hope that the Soviet Union would agree to their demands and instead expected a military confrontation.

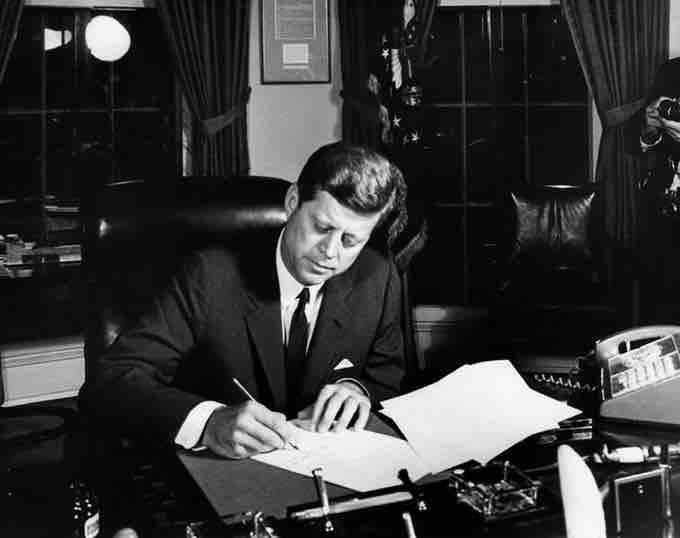

Containment of Cuba

Kennedy signs a proclamation that authorizes the naval containment of Cuba

On the Brink of Nuclear War

The ensuing crisis is generally regarded as the moment in which the Cold War came closest to turning into a nuclear conflict. It also marks the first documented instance of the threat of mutual assured destruction (MAD) being discussed as a determining factor in a major international arms agreement. As U.S. ships headed for Cuba, the army was told to prepare for war, and Kennedy appeared on national television to declare his intention to defend the Western Hemisphere from Soviet aggression.

Naval Blockade

A U.S. Navy plane flying over a Soviet cargo ship during the Cuban Crisis

The world held its breath awaiting the Soviet reply. Realizing how serious the United States was, Khrushchev sought a peaceful solution to the crisis, overruling those in his government who urged a harder stance. Behind the scenes, Robert Kennedy and Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin worked toward a compromise that would allow both superpowers to back down without either side’s seeming intimidated by the other. On October 26, Khrushchev agreed to remove the Russian missiles in exchange for Kennedy’s promise not to invade Cuba. On October 27, Kennedy’s agreement was made public, and the crisis ended. Not made public, but nevertheless part of the agreement, was Kennedy’s promise to remove U.S. warheads from Turkey and Italy, which were as close to Soviet targets as the Cuban missiles had been to American ones.

The showdown between the United States and the Soviet Union over Cuba’s missiles had put the world on the brink of a nuclear war. Both sides already had long-range bombers with nuclear weapons airborne or ready for launch and were only hours away from the first strike. As a result, a telephone “hot line” was installed, linking Washington D.C. and Moscow to avert future crises, and in 1963, Kennedy and Khrushchev signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, prohibiting tests of nuclear weapons in Earth’s atmosphere.

An additional outcome of this Kennedy-Khrushchev Pact that ended the Cuban Missile Crisis was that it effectively strengthened Castro's position by guaranteeing that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. Furthermore, because the withdrawal of the missiles in Italy and Turkey was not made public at the time, Khrushchev appeared to have lost the conflict.