The Fair Deal

The Fair Deal was the term given to United States President Harry S. Truman's ambitious set of proposals to Congress that he introduced in his January 1949 State of the Union address. The term has also been used to describe the domestic reform agenda of the Truman Administration, which governed the United States from 1945 to 1953, and marked a new stage in modern liberalism in the United States. Because Congress was dominated by conservatives during the Truman administration, however, major Fair Deal initiatives did not become law.

The most important proposals of the Fair Deal were aid to education, universal health insurance, legislation on fair employment and repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act. All were debated at length, but ultimately voted down. Nevertheless, some smaller and less controversial items passed. Additionally, Lyndon B. Johnson credited Truman's unfulfilled program as influencing Great Society measures such as Medicare, which Johnson successfully enacted during the 1960's.

Truman's Vision

In his 1949 State of the Union address, Truman stated that "every segment of our population, and every individual, has a right to expect from his government a fair deal." Truman's multitudinous proposed measures included federal aid to education, a large tax cut for low-income earners, the abolition of poll taxes, an anti-lynching law, a permanent FEPC, a farm aid program, increased public housing, an immigration bill, new TVA-style public works projects, the establishment of a new Department of Welfare, the repeal of the Taft-Hartley Act, an increase in the minimum wage from 40 to 75 cents an hour, national health insurance, expanded Social Security coverage and a $4 billion tax increase to reduce the national debt and finance these programs.

Philosophies of the Fair Deal

A liberal Democrat, Truman was determined both to continue the legacy of the New Deal and make his own mark in social policy. The liberal task of the Fair Deal was to spread the abundant benefits throughout society by stimulating economic growth. In September 1945, Truman presented to Congress a 21 point program of domestic legislation that outlined a series of proposed actions involving economic development and social welfare.

Solidly based upon the New Deal tradition of Truman's predecessor FDR in its advocacy of wide-ranging social legislation, the Fair Deal differed enough to claim a separate identity for Truman. The Depression did not return after the war and the Fair Deal had to contend with prosperity and an optimistic future. The Fair Dealers thought in terms of abundance rather than depression scarcity. Economist Leon Keyserling argued that the liberal task was to spread the benefits of abundance throughout society by stimulating economic growth. Agriculture Secretary Charles F. Brannan wanted to unleash the benefits of agricultural abundance and to encourage the development of an urban-rural Democratic coalition. However the Brannan Plan was defeated by strong conservative opposition in Congress and by his unrealistic confidence in the possibility uniting urban labor and farm owners who distrusted rural insurgency. The Korean War made military spending the nation's priority and killed almost the whole Fair Deal but did encourage the pursuit of economic growth.

Partisan Conflict

The Fair Deal was greatly opposed by the many conservative politicians (Republicans and Southern Democrats) who wanted the federal government's role to be reduced. After World War II, Americans were steadily becoming more conservative, as they were eager to enjoy prosperity not seen in the country since before the Great Depression.

Therefore, many of Truman's proposed reforms were never realized. In the 1946 congressional elections, Republicans gained majorities in both houses of Congress for the first time since 1928, and set their sights on reversing the liberal direction of the Roosevelt years. Despite this major momentum shift for Republicans, Truman was not discouraged, and his proposals to Congress became more and more abundant over the course of his presidency.

However, despite strong opposition, there were elements of Truman’s agenda that did win congressional approval, such as the public housing subsidies cosponsored by Republican Robert A. Taft under the 1949 National Housing Act, which funded slum clearance and the construction of 810,000 units of low-income housing over a period of six years.

Truman was also helped by the election of a Democratic Congress later in his term. According to Eric Leif Davin, the 1949-50 Congress: "was the most liberal Congress since 1938 and produced more 'New-Deal-Fair-Deal' legislation than any Congress between 1938 and Johnson’s Great Society of the mid-1960s.”

Impact

Economic Prosperity

Although Truman was unable to implement his Fair Deal program in its entirety, a great deal of social and economic progress took place in the late Forties and early Fifties. A Census report confirmed that gains in housing, education, living standards, and income under the Truman administration were unparalleled in American history. By 1953, 62 million Americans had jobs, a gain of 11 million in seven years, while unemployment had all but vanished. Farm income, dividends, and corporate income were at all-time highs, and there had not been a failure of an insured bank in nearly nine years. The minimum wage had also been increased while Social Security benefits had been doubled, and 8 million veterans had attended college by the end of the Truman administration as a result of the G.I. Bill, which subsidized the businesses, training, education, and housing of millions of returning veterans.

Millions of homes had been financed through previous government programs, and a start was made in slum clearance. Poverty was also significantly reduced, with one estimate suggesting that the percentage of Americans living in poverty had fallen from 33% of the population in 1949 to 28% by 1952. Incomes had risen faster than prices, which meant that real living standards were considerably higher than seven years earlier.

Civil Rights Achievements

Progress had also been made in civil rights, with the desegregation of both the federal civil Service and the armed forces and the creation of the Commission on Civil Rights. In fact, according to one historian, Truman had “done more than any President since Lincoln to awaken American conscience to the issues of civil rights."

As President, he put forward many civil rights programs but they were met with a lot of resistance by southern Democrats. All his legislative proposals were blocked. However, he used presidential executive orders to end discrimination in the armed forces and denied government contracts to firms with racially discriminatory practices. He also named African Americans to federal posts. Except for nondiscrimination provisions of the Housing Act of 1949, Truman had to be content with civil rights' gains achieved by executive order or through the federal courts. Vaughan argues that by continuing appeals to Congress for civil rights legislation, Truman helped reverse the long acceptance of segregation and discrimination by establishing integration as a moral principle.

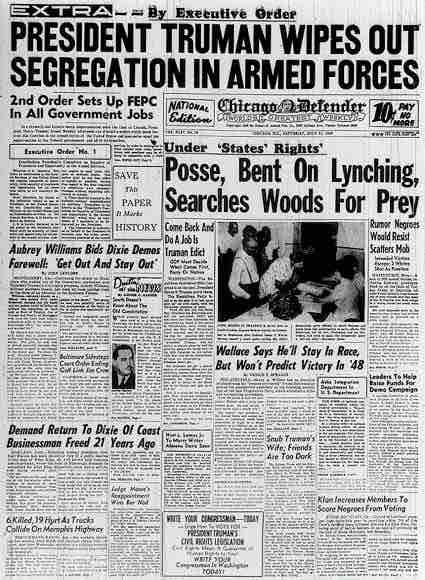

Truman's executive order wipes out segregation in armed forces, July 31, 1948

Although, when a Senator, Harry S. Truman did not support the nascent Civil Rights Movement, he included many civil rights initiatives and programs into his domestic reform agenda upon becoming President. This agenda was called the "Fair Deal. " As shown in this news headline, Truman used the power of the executive order to desegregate the armed forces.

Legacy

Despite a mixed record of legislative success, the Fair Deal remains significant in establishing the call for universal health care as a rallying cry for the Democratic Party. Lyndon B. Johnson credited Truman's unfulfilled program as influencing Great Society measures such as Medicare that Johnson successfully enacted during the 1960s.