Truman Doctrine and the Greek Civil War

TThe Truman Doctrine was an American foreign policy created to counter Soviet geopolitical spread during the Cold War. It was first announced to Congress by President Harry S. Truman on March 12, 1947 and further developed on July 12, 1948 when he pledged to contain Soviet threats to Greece and Turkey. American military force was usually not involved, but Congress appropriated free gifts of financial aid to support the economies and the military of Greece and Turkey. More generally, the Truman doctrine implied American support for other nations threatened by Soviet communism. The Truman Doctrine became the foundation of American foreign policy, and led, in 1949, to the formation of NATO, a military alliance that is still in effect. Historians often use Truman's speech to date the start of the Cold War.

Truman told Congress that "it must be the policy of the United States to support free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." Truman reasoned that because the totalitarian regimes coerced free peoples, they represented a threat to international peace and the national security of the United States. Truman made the plea amid the crisis of the Greek Civil War (1946–49). He argued that if Greece and Turkey did not receive the aid that they urgently needed, they would inevitably fall to communism with grave consequences throughout the region. Because Turkey and Greece were historic rivals, it was necessary to help both equally even though the threat to Greece was more immediate.

The policy won the support of Republicans who controlled Congress and sent $400 million in American money, but no military forces, to the region. The effect was to end the Communist threat, and in 1952 both countries (Greece and Turkey) joined NATO, a military alliance that guaranteed their protection.

Basis for the Policy of Containment

The Truman Doctrine was informally extended to become the basis of American Cold War policy throughout Europe and around the world. It shifted American foreign policy toward the Soviet Union from détente (a relaxation of tension) to a policy of containment of Soviet expansion as advocated by diplomat George Kennan. It was distinguished from rollback by implicitly tolerating the previous Soviet takeovers in Eastern Europe.

The Truman Doctrine underpinned American Cold War policy in Europe and around the world, and endured because it addressed a broader cultural insecurity regarding modern life in a globalized world. It dealt with U.S. concern over communism's domino effect and it mobilized American economic power to modernize and stabilize unstable regions without direct military intervention. It brought nation-building activities and modernization programs to the forefront of foreign policy.

The Truman Doctrine became a metaphor for emergency aid to keep a nation from communist influence. Truman used disease imagery not only to communicate a sense of impending disaster in the spread of communism but also to create a "rhetorical vision" of containing it by extending a protective shield around non-communist countries throughout the world.

The Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program) was an American initiative to aid Western Europe, in which the United States gave $13 billion in economic support to help rebuild Western European economies after the end of World War II. The initiative was named after Secretary of State George Marshall. The Plan was largely the creation of State Department officials such as George F. Kennan. The plan was established on June 5, 1947, and was in operation for four years beginning in April 1948.

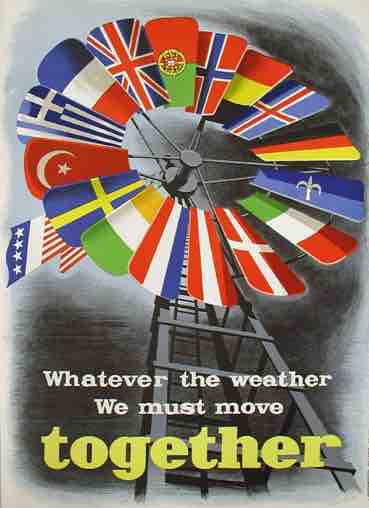

Marshall Plan Poster

One of a number of posters created to promote the Marshall Plan in Europe. Note the pivotal position of the American flag.

Goals of the Plan

The Marshall Plan sought to rebuild a war-devastated region, modernize industry, bolster European currency, and facilitate international trade, especially with the United States, whose economic interest required Europe to become wealthy enough to import U.S. goods. One of the main goals, however, was to contain the growing Soviet influence in Europe and prevent the spread of communism. The Marshall Plan required a lessening of interstate barriers, a dropping of many regulations, and encouraged an increase in productivity, labour union membership, as well as the adoption of modern business procedures.

The Hunger-Winter of 1947

Thousands protest in West Germany against the disastrous food situation (March 31, 1947). Sign: We want coal, we want bread. The Marshall Plan was designed to help rebuild war-torn Europe, and thus make Europe less susceptible to Communist threats.

Marshall Plan and the Soviets

The Marshall Plan offered the same aid to the Soviet Union and its allies, but they did not accept it, as to do so would be to allow a degree of U.S. control over the Communist economies. The non-participation of Eastern Europe was one of the first clear signs that the continent was now divided.

Aid Amounts

The Marshall Plan aid was divided amongst the participant states on a roughly per capita basis. A larger amount was given to the major industrial powers, as the prevailing opinion was that their resuscitation was essential for a general European revival.

During the four years that the plan was operational, $13 billion in economic and technical assistance was given to help the recovery of the European countries that had joined in the Organization for European Economic Co-operation. This was on top of $13 billion in American aid already given.

European Growth under the Plan

By 1952, as the funding ended, the economy of every participant state had surpassed pre-war levels; for all Marshall Plan recipients, economic output in 1951 was at least 35% higher than in 1938. Over the next two decades, Western Europe enjoyed unprecedented growth and prosperity, but economists are not sure what proportion was directly or indirectly due to the Plan.

Marshall Plan and European Integation

The Marshall Plan was one of the first elements of European integration, as it erased trade barriers and set up institutions to coordinate the economy on a continental level—that is, it stimulated the total political reconstruction of western Europe. Many felt that European integration was necessary to secure the peace and prosperity of Europe, and thus used Marshall Plan guidelines to foster integration.

End of the Plan and its Legacy

The Marshall Plan was originally scheduled to end in 1953. Any effort to extend it was halted by the growing cost of the Korean War and rearmament. American Republicans hostile to the plan had also gained seats in the 1950 Congressional elections, and conservative opposition to the plan was revived. Thus the plan ended in 1951, though various other forms of American aid to Europe continued afterwards.

TThe political effects of the Marshall Plan may have been just as important as the economic ones. Marshall Plan aid allowed the nations of Western Europe to relax austerity measures and rationing, reducing discontent and bringing political stability. The communist influence on Western Europe was greatly reduced, and throughout the region communist parties faded in popularity in the years after the Marshall Plan. The trade relations fostered by the Marshall Plan helped forge the North Atlantic alliance that would persist throughout the Cold War. At the same time, the nonparticipation of the states of Eastern Bloc was one of the first clear signs that the continent was now divided.