Introduction

Slavery formed a cornerstone of the British Empire in the 18th century. Every colony had slaves, from the southern rice plantations in Charles Town, South Carolina, to the northern wharves of Boston. Slavery was more than a labor system; it also influenced every aspect of colonial thought and culture. The uneven relationship it engendered gave white colonists an exaggerated sense of their own status. English liberty gained greater meaning and coherence for whites when they contrasted their status to that of the unfree class of black slaves in British America. African slavery provided whites in the colonies with a shared racial bond and identity.

Increasing Demand for Slave Labor

Slavery, as a theory, had been a commonly accepted European practice long before the exploration of the New World. Drawing on ancient Greek and Roman history, pro-slavery defenders noted that enslaving prisoners of war was an acceptable alternative to execution—once an enemy had surrendered, it was believed to be the victor's right to claim the life of their enemy through death or enslavement. Hence, when the Portuguese slave traders started exploring the coast of Africa where it was customary for warring indigenous tribes to enslave each other, they began to buy these slaves for export to the New World colonies. Other pro-slavery advocates argued that it was their mission to convert African non-Christians (whom they referred to as "heathens") to Christianity and that slavery allowed them to do this more effectively.

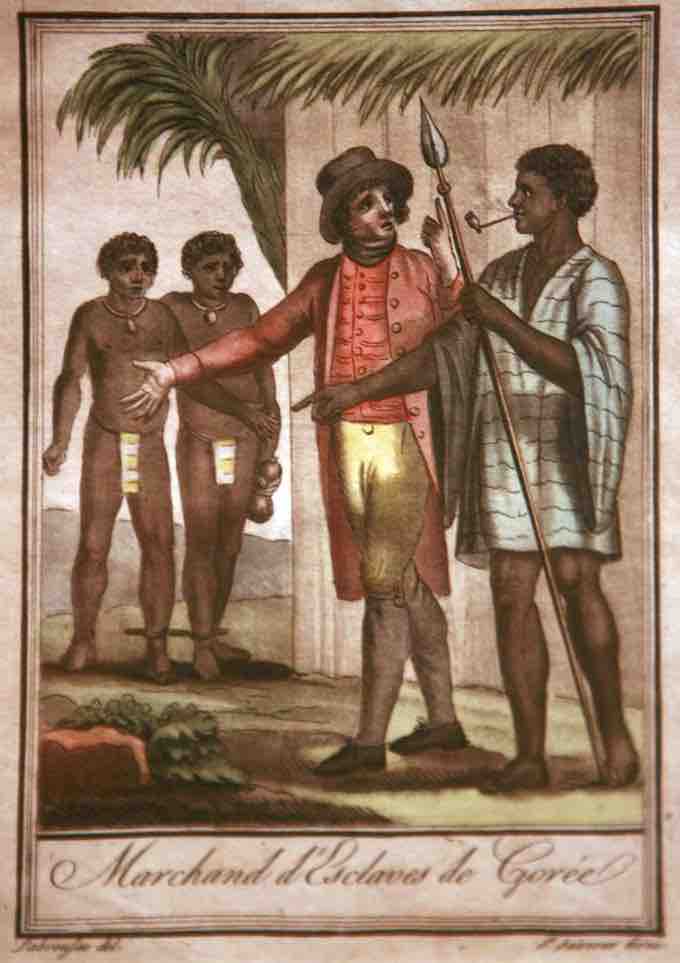

Slave traders in Gorés, by Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur

Depiction of European and African slave traders.

The European demand for New World cash crops, especially sugar, tobacco, rice, and cotton, led to a demand for labor to cultivate these crops. Although the practices of indentured servitude and the enslavement of American Indians was already in place, planters in the southern British colonies quickly came to favor enslaved Africans. Not only were Africans well suited to tropical climates, they also brought special skills and husbandry knowledge for crops such as rice, which the British found useful. Slavery and the African slave trade quickly became a building block of the colonial economy and an integral part of expanding and developing the British commercial empire in the Atlantic world.

Only a fraction of the enslaved Africans brought to the New World ended up in British North America. The vast majority of slaves shipped across the Atlantic were sent to the Caribbean sugar colonies, Brazil, or Spanish America. Throughout the Americas, but especially in the Caribbean, tropical disease took a large toll on the population. Unlike American Indians, Africans had a limited natural immunity to yellow fever and malaria; however, malnutrition, poor housing, inadequate clothing allowances, and overwork contributed to a high mortality rate which further increased the demand for the importation of Africans to replenish the labor supply.

Slavery in the British Colonies

The transport of slaves to the American colonies accelerated in the second half of the 17th century. In 1660, Charles II created the Royal African Company to trade in slaves and African goods. His brother, James II, led the company before ascending the throne. Under both these kings, the Royal African Company enjoyed a monopoly to transport slaves to the English colonies. Between 1672 and 1713, the company bought 125,000 captives on the African coast, losing 20% of them to death on the Middle Passage, the journey from the African coast to the Americas.

In the North American colonies, the importation of African slaves was directed mainly southward, where extensive tobacco, rice, and later, cotton plantation economies, demanded extensive labor forces for cultivation. In contrast to the high mortality rates of the Caribbean sugar plantations, North American slave populations tended to live longer. By the 19th century, many southern farmers found that natural increase was a viable alternative to importation in order to replenish their slave populations.

Slave Resistance

Slaves everywhere resisted their exploitation and attempted to gain freedom through armed uprisings and rebellions, such as the Stono Rebellion and the New York Slave Insurrection of 1741. Other less violent means of resistance included sabotage, running away, and slow labor paces on the plantations. Unlike their counterparts in the Caribbean, however, American slaves never successfully overthrew the system of slavery in the colonies and would not gain freedom until legislative decree made after the United States Civil War.