Introduction: The Election of 1828

The U.S. presidential election of 1828 featured a rematch between John Quincy Adams, the incumbent president, and Andrew Jackson, the runner-up in the 1824 election. With no other major candidates, Jackson and his chief ally, Martin Van Buren, consolidated their bases in the South and New York and easily defeated Adams. The Democratic Party derived its strength from the existing supporters of Jackson and their coalition with the supporters of Crawford (the Old Republicans) and Vice President Calhoun.

The election marked the rise of Jacksonian democracy on the national stage and the transition from the First Party System, of which Jeffersonian democracy was characteristic, to the Second Party System. Historians debate the significance of the election, with many arguing that it marked the beginning of modern American politics and the formation of the two-party system.

Nominations

The nomination of the Democratic Party was Andrew Jackson, former senator from Tennessee. Jackson accepted the incumbent vice president, John C. Calhoun, as his running mate. Jackson's supporters called themselves "Democrats," thus marking the evolution of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party into the modern Democratic Party.

The National Republican Party nomination was John Quincy Adams (of Massachusetts), the incumbent president of the United States. Adams accepted Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush of Pennsylvania as his vice presidential running mate. Adams supporters called themselves "National Republicans," and were antecedents of the Whig Party of the 1830s and, later, the Republican Party.

General Election

Campaign

The 1828 campaign differed significantly from earlier presidential contests because of the party organization that promoted Andrew Jackson. Jackson and his supporters reminded voters of the “corrupt bargain” of 1824. They framed it as the work of a small group of political elites, who, acting in a self-serving manner and ignoring the will of the majority, decided who would lead the nation. From Nashville, Tennessee, the Jackson campaign organized supporters around the nation through editorials in partisan newspapers and other publications. Pro-Jackson newspapers heralded the “hero of New Orleans” while denouncing Adams. Though he did not wage an election campaign filled with public appearances, Jackson did give one major campaign speech in New Orleans on January 8, the anniversary of the defeat of the British in 1815. He also engaged in rounds of discussion with politicians who came to his home, the Hermitage, in Nashville.

At the local level, Jackson’s supporters worked to bring in as many new voters as possible. Rallies, parades, and other rituals further broadcast the message that Jackson represented the common man, who stood in contrast to the corrupt elite backing Adams and Clay. Democratic organizations called "Hickory Clubs," a tribute to Jackson’s nickname, "Old Hickory," also worked tirelessly to ensure his election.

The campaign was marked by an impressive amount of mudslinging. Jackson was attacked for his marriage, his court martial and execution of deserters, his massacres of American Indian villages, and his habit of dueling. It was charged that Adams, while serving as minister to Russia, had surrendered an American servant girl to the appetites of the czar. Adams also was accused of using public funds to buy gambling devices for the presidential residence; however, further investigation failed to substantiate these claims.

Results

The selection of electors began on October 31, 1828, with elections in Ohio and Pennsylvania, and ended on November 13 with elections in North Carolina. The Electoral College met on December 3.

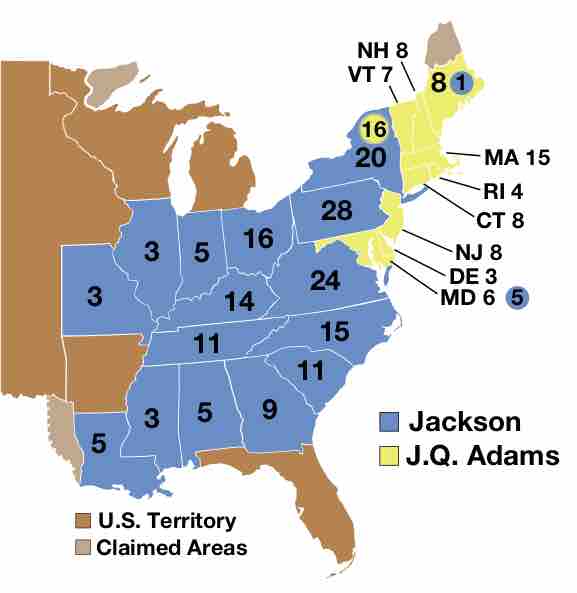

Adams won the New England states, New Jersey, and Delaware. In addition, Adams picked up Maryland. Jackson won everything else, however, capturing 56 percent of the popular vote and 68 percent of the electoral vote and resulting in an overwhelming victory over Adams. As in 1800, when Jefferson had won over the Federalist incumbent, John Adams, the presidency passed to a new political party, the Democrats. The election was the climax of several decades of expanding democracy in the United States and the end of the older politics of deference.

Electoral College votes in the election of 1828

This map illustrates the Electoral College votes for Jackson and Adams for each state. Jackson won the majority by a landslide, with Adams only winning the New England states, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland.