Introduction: The "Era of Good Feelings"

The "Era of Good Feelings" marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. The era saw a brief lull in the bitter partisan disputes that had plagued the Democratic-Republican and Federalist parties. President James Monroe endeavored to consolidate the Republican and Federalist parties, with the ultimate goal of eliminating parties altogether from national politics.

The designation of the period by historians as one of good feelings is often conveyed with irony or skepticism, as the political atmosphere of the era was strained and divisive, especially among factions within the Monroe administration and the Republican Party.

Post-War Nationalism

The "Era of Good Feelings" began in 1815 in the mood of victory that swept the nation at the end of the War of 1812. Exaltation replaced the bitter political divisions between Federalists and Republicans, between northern and southern states, and between east-coast cities and settlers on the western frontier. The Federalist Party largely dissolved after the Hartford Convention in 1814–15, and subsequently, political bitterness declined. The Democratic-Republican Party was nominally dominant but was also largely inactive at the national level and in most states.

The era saw a national trend that envisioned a permanent role for the federal government in developing the nation's prosperity. Madison announced this shift in policy with his "Seventh Annual Message to Congress" in December of 1815, which authorized measures for a national bank and a protective tariff on manufactures. The emergence of new Republicans, undismayed by mild nationalist policies, anticipated Monroe's "Era of Good Feelings," and a general mood of optimism emerged with hopes for political reconciliation.

Monroe and Political Parties

The method Monroe employed to encourage the deflating of the Federalist Party was largely one of neglect: He denied them all political patronage, administrative appointments, and federal support of any kind. Monroe pursued this policy dispassionately and without any desire to persecute the Federalists, however. His purpose was simply to remove the Federalists from positions of political power, both at the federal and state levels, especially in Federalism's New England strongholds.

In his public pronouncements, Monroe was careful to make no comments that could be interpreted as politically partisan. In his private encounters with Federalists, he made favorable impressions—committing himself to nothing, yet eliciting good feelings.

Great Goodwill Tours

Perhaps Monroe's countrywide goodwill tours in 1817 and 1819 were the greatest expression of the "Era of Good Feelings." His visits to New England and the Federalist stronghold of Boston, Massachusetts, were the most significant of the tour. Here, the descriptive phrase "Era of Good Feelings" was bestowed by a local Federalist journal by journalist Benjamin Russell. Monroe achieved the primary goal of his tour in the heart of Federalist territory. Monroe was assiduous in avoiding any remarks or expressions that might chasten or humiliate his hosts. He presented himself strictly as the head of state and not as the leader of a triumphant political party.

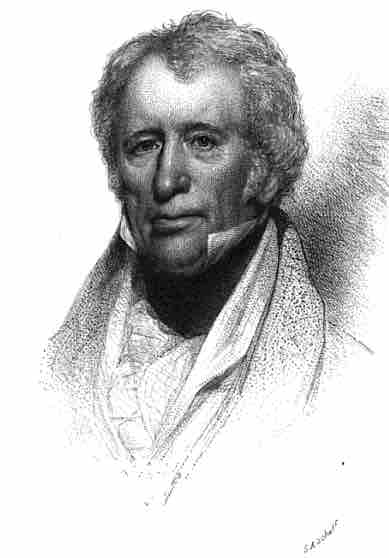

Benjamin Russell, American journalist

Russell, pictured above, coined the term "Era of Good Feelings" during Monroe's goodwill tour in 1817.

Failure of Amalgamation

Monroe's success in mitigating party rancor produced an appearance of political unity, with almost all Americans identifying themselves as Republicans. His nearly unanimous electoral victory for reelection in 1820 seemed to confirm this unity.

Recognizing the danger of intraparty rivalries, Monroe attempted to include prospective presidential candidates and top political leaders in his administration. His cabinet comprised three of the political rivals who would vie for the presidency in 1824: John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, and William H. Crawford. A fourth, Andrew Jackson, held high military appointments. Monroe felt he could manage the factional disputes and arrange compromise on national politics within administration guidelines. His great disadvantage, however, was that amalgamation deprived him of appealing to Republican solidarity that would have cleared the way for passage of his programs in Congress. The end result was a loss of party discipline.

Old Republican critics of the new nationalism, among them John Randolph of Roanoke, Virginia, had warned that the abandonment of the Jeffersonian scheme of Southern preeminence would provoke a sectional conflict between the North and the South that would threaten the Union. Old Republicans feared such an outcome was inevitable if universal adherence to the precepts of Jeffersonianism was absent.

The disastrous, yet brief, Panic of 1819 and the Supreme Court's case of McCulloch v. Maryland reanimated the disputes over the supremacy of state sovereignty and federal power. The Missouri Crisis in 1820 made the explosive political conflict between slave and free states open and explicit. With the decline in political consensus, Jeffersonian principles were indeed revived on the basis of Southern exceptionalism, and the interlude of the "Era of Good Feelings" came to an end.