Introduction

The issue of voting rights in the United States has been contentious throughout the country's history. Eligibility to vote in the United States is determined by both federal and state law. Currently, only U.S. citizens can vote in U.S. elections, although this has not always been the case. Who is, or who can become, a citizen is governed on a national basis by federal law. In the absence of a federal law or constitutional amendment, each state is given considerable discretion to establish qualifications for suffrage and candidacy within its own jurisdiction.

At the time of ratification of the Constitution, most states used property qualifications to restrict franchise. When the country was founded, only white men with real property (land) or sufficient wealth for taxation were permitted to vote in most states. Freed African Americans were allowed to vote in only four states. White men without property, almost all women, and all other people of color were denied the right to vote.

By the time the American Civil War had begun, however, most white men were allowed to vote, whether or not they owned property. Literacy tests, poll taxes, and even religious tests were used in various places to determine voter eligibility, and most white women, people of color, and American Indians still could not vote.

Suffrage in the Time of Jacksonian Democracy

Jacksonian democracy is the political movement toward greater democracy for the common man typified by U.S. President Andrew Jackson and his supporters. Jackson's policies followed the era of Jeffersonian democracy that dominated the previous political era. Jackson's supporters began to form the modern Democratic Party and fought against their rival Adams and Anti-Jacksonian factions, which soon emerged as the Whigs.

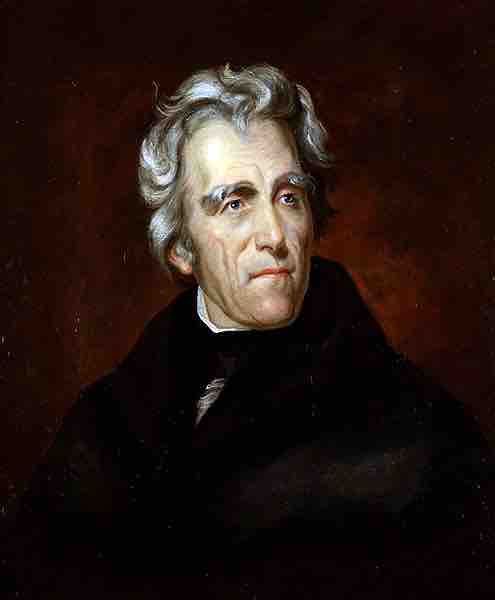

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States (1829–1837).

Leading up to and during the Jacksonian era, suffrage was extended to nearly all white male adult citizens. New states adopted constitutions that did not contain property qualifications for voting, a move designed to stimulate migration across their borders. Vermont and Kentucky, admitted to the Union in 1791 and 1792 respectively, granted the right to vote to all white men regardless of whether they owned property or paid taxes. Ohio’s state constitution placed a minor taxpaying requirement on voters but otherwise allowed for expansive white male suffrage. Alabama, admitted to the Union in 1819, eliminated property qualifications for voting in its state constitution. Two other new states, Indiana (1816) and Illinois (1818), also extended the right to vote to white men regardless of property. Initially, the new state of Mississippi (1817) restricted voting to white male property holders, but in 1832, it eliminated this provision. By 1850, nearly all voting requirements to own property or pay taxes had been dropped.

The fact that white men were now legally allowed to vote did not necessarily mean they routinely would, however. Many had to be pulled to the polls, which became the most important role of local political parties. These political parties systematically sought out potential voters and brought them to the polls. Voter turnout soared during the Jacksonian era, reaching about 80 percent of the adult white men by 1840.

Disenfranchisement

Expanded voting rights did not extend to women, American Indians, or free African Americans in the North or South. Indeed, race replaced property qualifications as the criterion for voting rights. American democracy had a decidedly racist orientation; a white majority limited the rights of black minorities. New Jersey explicitly restricted the right to vote to white men only. Connecticut passed a law in 1814 taking the right to vote away from free black men and restricting suffrage to white men only. By the 1820s, 80 percent of the white male population could vote in New York State elections; no other state had expanded suffrage so dramatically. At the same time, however, New York effectively disenfranchised free black men in 1822 (black men had had the right to vote under the 1777 constitution) by requiring that “men of color” possess property valuing more than $250—an exorbitant amount at the time.

The Supreme Court of North Carolina originally upheld the ability of free African Americans to vote before they were disenfranchised by the decision of the North Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1835. At the same time, convention delegates relaxed religious and property qualifications for whites.