Indian Removal

Indian removal was a nineteenth-century policy of the U.S. government to relocate American Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River to lands west of the river. The Indian Removal Act was signed into law by President Jackson in 1830, and it had a profound and devastating impact on the lives of Americans. For white land-hungry Southerners, the policy allowed for a prosperous westward expansion. For American Indians, the Removal Act brought death and destruction. While the United States eventually tripled in size, thousands of American Indians lost their homes, their families, and often their lives in what many historians consider a sweeping genocide.

Since the presidency of Thomas Jefferson, The U.S. policy had been to allow American Indians to remain east of the Mississippi while simultaneously forcing them to assimilate and become "civilized." Jefferson's planned to control the American Indians by encouraging or coercing them to assume a sedentary agricultural lifestyle; by adopting such a lifestyle, they would become economically dependent on trade with white Americans and thereby willing to give up land in exchange for trade goods. In the early nineteenth century, the notion of "land exchange" developed: American Indians would relinquish land in the east in exchange for equal or comparable land west of the Mississippi River. This idea was proposed in 1803 by Jefferson, but was not used in actual treaties until 1817, when the Cherokee agreed to cede two large tracts of land in the east for one of equal size in present-day Arkansas. Many other treaties of this nature quickly followed.

Jacksonian Policy

Under Andrew Jackson, elected president in 1829, government policy toward American Indians moved from coercive to outright hostile. Jackson abandoned the policy of Jefferson and other predecessors and instead aggressively pursued plans to remove all American Indian tribes living in the southeastern states, regardless of whether they had assimilated to white culture or become "civilized." At Jackson's request, the U.S. Congress opened a fierce debate on an Indian Removal Bill. In the end, the bill passed, but the vote was close. The Senate passed the measure 28–19 and the House 102–97. Jackson signed the legislation into law on June 30, 1830.

In 1830, the majority of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and Cherokee were living east of the Mississippi as they had for thousands of years. Jackson's Removal Act called for relocation of all tribes to lands west of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the American Indian tribes, it authorized the president to negotiate land-exchange treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States.

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

The first removal treaty signed after the Removal Act was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which Choctaws in Mississippi ceded land east of the river in exchange for payment and land in the west. Two years prior, the state legislature of Georgia enacted a series of laws that stripped the Cherokee of their rights under the state law with the hope of forcing tribe members off of their fertile and gold-sprinkled land. By the 1830s, many of the five major tribes in that area had assimilated into the dominant culture; some even owned slaves. In 1831, members of these tribes decided to use the U.S. Supreme Court to combat Jacksonian policies in the case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia.

In June of 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief John Ross selected (at the urging of Senators Daniel Webster and Theodore Frelinghuysen) William Wirt, attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, to defend Cherokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Cherokee Nation asked for an injunction, claiming that Georgia's state legislation had created laws designed to annihilate the Cherokees as a political society. Wirt argued that Georgia violated the U.S. Constitution as well as United States-Cherokee treaties. In 1832, the U.S. Supreme Court decision (Worcester v. Georgia ) ruled that Georgia could not impose its laws upon Cherokee tribal lands. However, the state and President Jackson refused to accept or enforce the decision.

The Trail of Tears

Jackson used the Georgia crisis to pressure Cherokee leaders to sign a removal treaty. A small faction of Cherokees, led by John Ridge, negotiated the Treaty of New Echota with Jackson's representatives. Ridge was not a recognized leader of the Cherokee Nation, and this document was rejected by most Cherokees as illegitimate. More than 15,000 Cherokees signed a petition in protest of the proposed removal; however, the Supreme Court and the U.S. legislature ignored the list.

President Van Buren, Jackson's successor, enforced the treaty and ordered 7,000 armed troops to remove the Cherokees. Due to the infighting between political factions, many Cherokees thought their appeals were still being considered until troops arrived. This abrupt and forced removal resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 Cherokees on what became known as the "Trail of Tears." By 1837, 46,000 American Indians from southeastern states had been removed from their homelands, leaving 25 million acres for white settlement and the expansion of slavery.

Trail of Tears

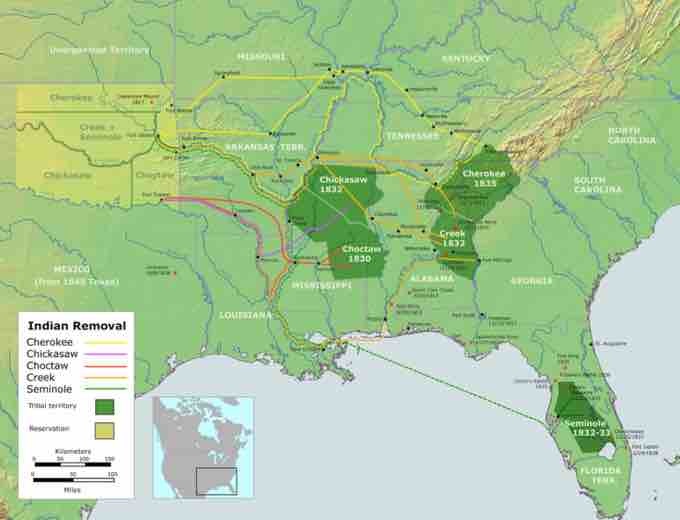

This map illustrates the route of the Trail of Tears. The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole were forced to march from various locations in the Southeastern United States to the Indian Territory located in present-day Oklahoma.

Resistance

In 1835, the Seminole tribe refused to leave their lands in Florida, leading to the Second Seminole War. Osceola led the Seminole in their fight against removal. Based in the Everglades of Florida, Osceola and his band used surprise attacks to defeat the U.S. Army in many battles. In 1837, Osceola was seized by deceit upon the orders of U.S. General T.S. Jesup when Osceola came under a flag of truce to negotiate peace. Osceola later died in prison. Some Seminole traveled deeper into the Everglades, while others moved west. Removal continued out west, and numerous wars over land ensued.

Legacy

In 1987, about 2,200 miles of trails were authorized by federal law to mark the removal of seventeen detachments of the Cherokee people. Called the "Trail of Tears National Historic Trail," it traverses portions of nine states and includes land and water routes.