Introduction: The Dorr Rebellion

The Dorr Rebellion (1841–1842) was a short-lived, armed insurrection in the U.S. state of Rhode Island led by Thomas Wilson Dorr, who was agitating for changes to the state's electoral system. The Rebellion demonstrated that as average citizens became more involved in political issues, conflict was possible and did occur. The event can be viewed as symptomatic of an era in which citizens became more passionate about and partisan in their political beliefs.

Precursors

Under Rhode Island's charter, only white male landowners could vote. At a time when most of the citizens of the colonies were farmers, this was considered fairly democratic. By the 1840s, property worth at least $134 was required in order to vote. However, as the Industrial Revolution reached North America and people moved to cities, fewer people owned land.

By 1829, 60 percent of the state's white men were ineligible to vote (as were all women and most non-white men), meaning that the electorate of Rhode Island was made up of only 40 percent of the state's white men. Those who wished to extend white male suffrage argued that the charter was un-republican and violated the U.S. Constitution's Guarantee Clause, which stated, "The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government... ."

Before the 1840s, there had been several attempts to approve a new state constitution that provided broader voting rights; however, all had failed. The charter lacked a procedure for amendment, and the Rhode Island General Assembly had consistently failed to liberalize the constitution by extending voting rights, enacting a bill of rights, or reapportioning the legislature. By 1841, Rhode Island was one of the few states without universal suffrage for white men.

Rebellion

Thomas Wilson Dorr and the People's Convention

In 1841, suffrage supporters led by politician and reformer Thomas Wilson Dorr gave up on attempts to change the system from within. In October, Dorr's supporters held the People's Convention and drafted a new constitution that granted the vote to all white men with one year's residence in the state. At the same time, the state's General Assembly formed a rival convention and drafted the Freemen's Constitution, which made some concessions to democratic demands.

Late in that year, the two constitutions were voted on, with the Freemen's Constitution being defeated in the legislature largely by Dorr supporters. The People's Convention version was overwhelmingly supported in a referendum in December. Although much of the support for the People's Convention constitution came from newly eligible voters, Dorr claimed that most of those eligible under the old constitution also had supported it, making it legal.

Two Governments

In early 1842, both groups organized elections of their own, leading in April to the selections of both Dorr and Samuel Ward King as Governors of Rhode Island. King showed no signs of introducing the new constitution, and when matters came to a head, he declared martial law. On May 4, the state legislature requested the dispatch of federal troops to suppress the "lawless assemblages" rallying under Dorr. President John Tyler sent an observer but decided not to send soldiers. Nevertheless, Tyler, citing the U.S. Constitution, added that, "[i]f resistance is made to the execution of the laws of Rhode Island, by such force as the civil peace shall be unable to overcome, it will be the duty of this Government to enforce the constitutional guarantee—a guarantee given and adopted mutually by all the original States."

Attack on the Arsenal

Most of the state militiamen were Irishmen and newly enfranchised by the referendum, and consequently supported Dorr. The "Dorrites" led an unsuccessful attack against the arsenal in Providence on May 19, 1842. Defenders of the arsenal on the "Charterite" side (those who supported the original charter) included Dorr's father, Sullivan Dorr, and his uncle, Crawford Allen. At the time, these men owned the Bernon Mill Village in Woonsocket. After his defeat, Thomas Dorr and his supporters retreated to Chepachet where they hoped to reconvene the People's Convention.

Charterite forces were sent to Woonsocket to defend the village and to cut off the Dorrite forces' retreat. The Charterites fortified a house in preparation for an attack, but it never came, and the Dorr Rebellion soon fell apart. Governor King issued a warrant for Dorr's arrest with a reward of $5,000, and Dorr fled the state.

A Second Convention

The Charterites, finally convinced of the strength of the suffrage cause, called another convention. In September of 1842, a session of the Rhode Island General Assembly met in Newport and framed a new state constitution, which was ratified by the old, limited electorate and proclaimed by Governor King on January 23, 1843. The new constitution greatly liberalized voting requirements by extending suffrage to any free man, regardless of race, who could pay a poll tax of one dollar. It was accepted by both parties and took effect in May of 1843.

In Luther v. Borden (1849), the Supreme Court of the United States sidestepped the question of which state government was legitimate, finding it to be a political question best left to the other branches of the federal government.

Dorr's Fate

Dorr returned to Rhode Island later in 1843, was found guilty of treason against the state, and was sentenced in 1844 to solitary confinement and hard labor for life. The harshness of the sentence was widely condemned, and in 1845, Dorr, who had fallen ill, was released. His civil rights were restored in 1851. In 1854, the court judgment against him was set aside; he died later that year.

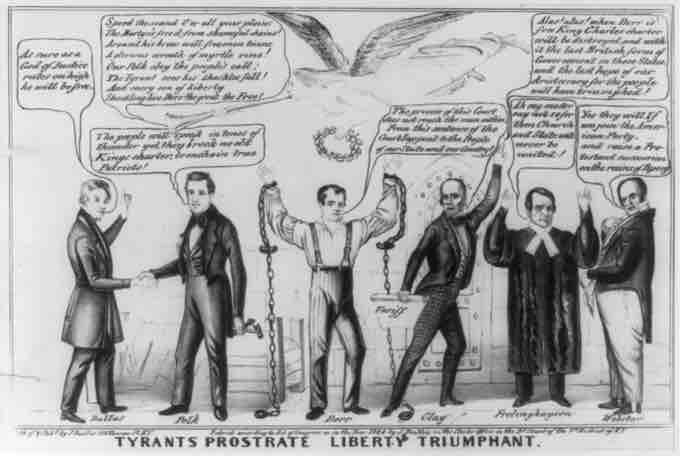

"Tyrants Prostrate Liberty Triumphant"

A polemic from Rhode Island (1844) in support of the Dorrite cause.