Obedience, in human behavior, is a form of social influence. It occurs when a person yields to explicit instructions or orders from an authority figure. Obedience is generally distinguished from compliance (behavior influenced by peers) and conformity (behavior intended to match that of the majority). Following the Second World War—and in particular the Holocaust—psychologists set out to investigate the phenomenon of human obedience. Early attempts to explain the Holocaust had focused on the idea that there was something distinctive about German culture that had allowed the Holocaust to take place. They quickly found that the majority of humans are surprisingly obedient to authority. The Holocaust resulted in the extermination of millions of Jews, Gypsies, and communists; it has prompted us to take a closer look at the roots of obedience—in part, so that tragedies such as this may never happen again.

Research on Obedience

Milgram

The Milgram experiment on obedience to authority figures (1963) was a series of social psychology experiments conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. These experiments measured the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience.

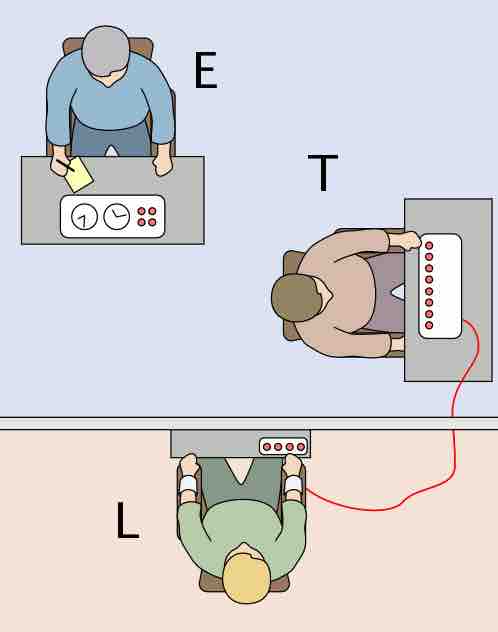

The experiments involved a "teacher" who conducted the experiment, a participant, and a confederate who pretended to be a volunteer. A confederate is someone who is a part of the experiment, but who pretends to be a participant in the study. The participant believed his role was randomly assigned.

Milgram experiment setup

Illustration of the setup of a Milgram experiment. The experimenter (E) convinces the subject (T) to give what he believes are painful electric shocks to another subject, who is actually an actor (L). Many subjects continued to give shocks despite pleas of mercy from the actors.

The participants were instructed that they had to shock a person in another room for every wrong answer on a learning task, and the shocks increased with intensity for each wrong answer. If participants questioned the procedure, the researcher would encourage them further. The person receiving the “shock” would make noises of pain, complain of heart pains, and even demonstrate seizure-like behavior.

At this point, many participants indicated their desire to stop the experiment and check on the confederate; however, most of them continued after being assured they would not be held responsible. If at any time the participant indicated his desire to halt the experiment, he was verbally encouraged to continue. If the participant still wished to stop after all the verbal prods, the experiment ended. Otherwise, it was only halted after the participant had given the maximum 450-volt shock three times in a row.

Milgram’s senior-level psychology students hypothesized that only a very small fraction of participants (1%) would inflict maximum voltage. In Milgram's first set of experiments, 65% of participants administered the full 450-volt shock, even though most were very uncomfortable doing so. Most participants paused and questioned the experiment at some point, but 26 out of 40 still administered the full shock, even after the confederate ceased to respond. These results demonstrate that participants were willing to obey an authority figure and administer extremely harmful (and potentially lethal) shocks.

Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford prison experiment was a study, conducted by Philip Zimbardo at Stanford University in 1971, of the psychological effects of becoming a prisoner or prison guard and. Twenty-four males students were selected to take on randomly assigned roles of prisoner or guard in a mock prison situated in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. The participants adapted to their roles beyond the experimenter's expectations. The guards enforced authoritarian measures and ultimately subjected some of the prisoners to psychological and physical torture. Many of the prisoners passively accepted abuse and, at the request of the guards, readily harassed other prisoners who attempted to prevent it. The experiment even affected Zimbardo himself, who, in his role as the superintendent, permitted the abuse to continue.

A fraction of the way through the experiment, Zimbardo announced an end to the study. It has been argued that the results of the study demonstrate the impressionability and obedience of people when provided with a legitimizing ideology, along with social and institutional support. The results indicate that environmental factors have a significant affect on behavior. In addition to environmental factors, Zimbardo attributes many of the guards' actions to deindividuation afforded by the authority position and even the anonymity of the uniforms. The Abu Ghraib prison scandal has been interpreted based on the results of this study, suggesting that deindividuation may also have impacted the guards' behavior in that situation.

Factors Influencing Obedience

After running these experiments, Milgram and Zimbardo concluded that the following factors affect obedience:

- Proximity to the authority figure: Proximity indicates physical closeness; the closer the authority figure is, the more obedience is demonstrated. In the Milgram experiment, the experimenter was in the same room as the participant, likely eliciting a more obedient response.

- Prestige of the experimenter: Something as simple as wearing a lab coat or not wearing a lab coat can affect levels of obedience; authority figures with more prestige elicit more obedience; both researchers have suggested that the prestige associated with Yale and Stanford respectively may have influenced obedience in their experiments.

- Expertise: A subject who has neither the ability nor the expertise to make decisions, especially in a crisis, will leave decision making to the group and its hierarchy.

- Deindividuation: The essence of obedience consists in the fact that people come to view themselves not as individuals but as instruments for carrying out others' wishes, and thus no longer see themselves as responsible for their actions.

Controversy and Obedience Experiments

The Milgram and Zimbardo experiments stand as dramatic demonstrations of the power of authority and other situational factors in human behavior. While we have learned and continued to learn from their results, they have been endlessly controversial. There is always controversy over exactly how to interpret social psychology experiments. Human behavior is extremely complex, and so there are always numerous variables to consider when interpreting such studies. But the ethical considerations raised by these studies are even more controversial. Specifically, the subjects were exposed to significant short-term stress, as well as potential long-term trauma. Additionally, neither Milgram nor Zimbardo informed subjects ahead of time of the nature of their participation. While a follow-up of Milgram’s participants indicated that they did not experience any long-term distress, Zimbardo’s prison participants did. Largely as a result of these experiments, ethical standards have been modified to protect participants.