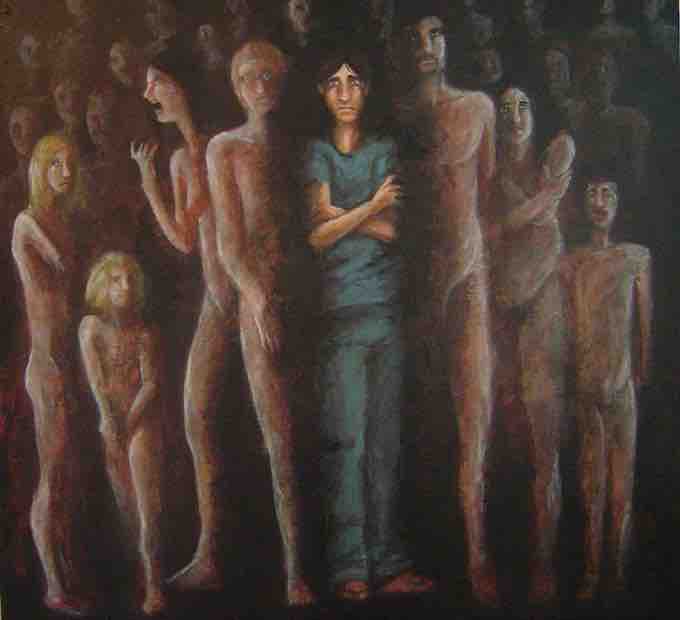

Dissociative States

In psychology, the term dissociation describes a wide array of experiences from mild detachment from immediate surroundings to more severe detachment from physical and emotional experience. Dissociation occurs on a continuum—at the nonpathological end of the continuum, dissociation describes common events such as daydreaming while driving a vehicle. Further along the continuum are non-pathological altered states of consciousness. More pathological dissociation involves dissociative disorders.

Most individuals have experienced a dissociative state at some point in their lives. Consider if you are talking to a friend and suddenly you realize that you blanked out and missed half the conversation; or consider if you've been driving somewhere familiar, and you realize halfway through the drive that you weren't fully paying attention but were instead on "auto-pilot." These are both examples of dissociation. Dissociation of this sort is fairly normal from time to time; however, there are five types of dissociative disorders which are considered psychopathological: dissociative identity disorder, disociative amnesia, depersonalization/derealization disorder, other specified dissociative disorder, and unspecified dissociative disorder.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Defining Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a rare mental disorder characterized by at least two distinct and relatively enduring identities or dissociated personality states that recurrently control a person's behavior; it is accompanied by memory impairment for important information not explained by ordinary forgetfulness. Amnesia in DID is understood to mean amnesia between two or more of the distinct identities; the host alter will experience "losing time" in the present another alter takes the place of the one the host alter. Rarely is the host alter aware of their time loss. Each of the distinct identities or personalities has its own way of perceiving, thinking about, and relating to itself and the environment.

Previously known as multiple personality disorder, DID became popularized in 1974 with the publication of the highly influential book (and later miniseries) Sybil. Describing what Robert Rieber called "the third most famous of multiple personality cases", it presented a detailed discussion of the problems of treatment of "Sybil", a pseudonym for Shirley Ardell Mason. Though the book and subsequent films helped popularize the diagnosis and trigger an epidemic of the diagnosis, later analysis of the case argue that Sybil may not have actually had DID.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative Identity Disorder is characterized by at least two distinct and relatively enduring identities or dissociated personality states that recurrently control a person's behavior, and is accompanied by memory impairment for important information not explained by ordinary forgetfulness. Each of the distinct identities or personalities has its own way of perceiving, thinking about, and relating to itself and the environment.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

In order to be diagnosed with DID, two or more distinct personality states/alters must present, and each must have their own way of being. The person must experience gaps in memory related to certain events or personal information that cannot be accounted for by ordinary forgetfulness. The disorder must lead to some kind of impairment in social, occupational, or daily life functioning, and the symptoms must not be attributed to normal cultural or religious practices (or fantasy play in children). Finally, these symptoms are not accounted for by substance abuse, seizures, or other medical conditions, nor by imaginative play in children.

Dissociative Amnesia

Defining Dissociative Amnesia

Amnesia refers to the partial or total forgetting of some experience or event. An individual with dissociative amnesia is unable to recall important personal information, usually following an extremely stressful or traumatic experience such as combat, natural disasters, or being the victim of violence. Some individuals with dissociative amnesia will also experience dissociative fugue (from the word “to flee” in French), whereby they suddenly wander away from their home, experience confusion about their identity, and sometimes even adopt a new identity (Cardeña & Gleaves, 2006). Most fugue episodes last only a few hours or days, but some can last longer.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

To be diagnosed with dissociative amnesia, an individual must be unable to recall autobiographic memory associated with a traumatic event. Usually the individual is unconsciously selective in their recall of trauma. They must feel distress by the inability to recall events; the cause must not be physiological; and the symptoms cannot be explained by common forgetfulness or be associated with any of the other dissociative disorders. Dissociative fugue, while it used to be its own diagnosis in the previous DSM-IV-TR, is now subsumed under dissociative amnesia as a specifier (i.e., dissociative amnesia with or without dissociative fugue). Dissociative amnesia must occur on more than one occasion and must impair some aspect of the individual's life (social, occupational, etc.).

Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder

Defining Depersonalization and Derealization

Depersonalization is defined as feelings of “unreality or detachment from, or unfamiliarity with, one’s whole self or from aspects of the self” (APA, 2013, p. 302). Individuals who experience depersonalization might believe their thoughts and feelings are not their own; they may feel robotic, as though they lack control over their movements and speech; they may experience a distorted sense of time; and, in extreme cases, they may sense an “out-of-body” experience in which they see themselves from the vantage point of another person. Derealization is conceptualized as a sense of “unreality or detachment from, or unfamiliarity with, the world, be it individuals, inanimate objects, or all surroundings” (APA, 2013, p. 303). A person who experiences derealization might feel as though they are in a fog or a dream or that the surrounding world is somehow artificial and unreal. An episode of depersonalization/derealization disorder can be as brief as a few seconds or continue for several years.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

To be diagnosed with depersonalization/derealization disorder, a person must consistently have a feeling of both or either depersonalization or derealization. Reality testing must remain intact, and the symptoms must not be attributed to substance use or another mental illness. As with any dissociative disorder, the symptoms must be severe enough to cause clinically significant distress or significantly impair the individual's functioning in at least one major area of life (e.g., work or social life).

Other Specified Dissociative Disorder and Unspecified Dissociative Disorder

The old category of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified is now split into two according to the DSM-5 (2013): other specified dissociative disorder and unspecified dissociative disorder. These categories are used for forms of pathological dissociation that do not fully meet the criteria of the other dissociative disorders, or if the correct category has not been determined. Other specified dissociative disorder covers a variety of different presentation, including some symptoms similar to DID but not matching the distinct criteria. Unspecified dissociative disorder is often used in an emergency room setting where there is insufficient information to make a diagnosis.

Etiology

The International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation states that the prevalence of DID is between 1-3% of the general population, and the disorder is diagnosed more frequently in females than in males. In the late 20th century there was a revived interest in DID and the number of cases rose sharply. The cause of the sudden increase of cases is not clear; it may be attributed to an actual rise in cases, or it may be attributed to the increased awareness, which revealed previously undiagnosed cases.

DID is a controversial disorder, primarily surrounding its causation. Some believe DID is caused by traumatic stress that forces the mind to split into multiple identities, each with a separate set of memories; others believe that individuals who are diagnosed with DID are highly suggestible and may be subconsciously acting out a role that they believe the therapist is expecting. Some clinicians assert that DID cannot be accurately diagnosed because of vague and unclear diagnostic criteria, including undefined concepts such as "personality state" and "identities."

Severe sexual, physical, or psychological trauma in childhood have been proposed as explanations for the development of dissociative disorders, especially DID. In DID, these events are thought to disrupt the development of a unified personality in childhood. Awareness, memories and emotions related to the trauma are removed from consciousness, and alternate personalities or subpersonalities are formed with differing memories, emotions, and behavior. The initial theoretical description of DID was that dissociative symptoms were a means of coping with extreme stress and trauma; however, research on this hypothesis is inconclusive. The majority of patients with DID report severe childhood sexual and/or physical abuse, though some argue that the accuracy of these reports is controversial. Like DID, other dissociative disorders are thought to develop as a response to severe trauma, either in childhood or adulthood.

Treatment

Dissociative disorders are generally treated with long-term psychotherapy. Common treatment methods include an eclectic mix of psychotherapy techniques, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), insight-oriented therapies, dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), hypnotherapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR).

In the case of DID, the majority of individuals with the disorder seek treatment for other psychological problems, such as depression, and DID is often difficult to detect. It may take a therapist years to notice symptoms of DID. There is a general lack of consensus in the treatment of DID, and research on treatment effectiveness focuses mainly on clinical approaches described in case studies. General treatment guidelines suggest a phased, eclectic approach with more concrete guidance and agreement on early stage; however no systematic, empirically-supported approach exists, and later stages of treatment have no consensus. Even highly experienced therapists have few patients that achieve a unified identity.

Unlike DID, the length of an event of dissociative amnesia may be a few minutes or several years. If an episode is associated with a traumatic event, the amnesia may clear up when the person is removed from the traumatic situation. Similarly, once dissociative fugue is discovered and treated, many people recover quickly.

Medications can be used for comorbid (co-occurring) disorders and/or targeted symptom relief. These medications (such as antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, or tranquilizers) can help control the mental health symptoms associated with the disorders; however, there are no medications that specifically treat dissociative disorders.