Because we spend so many years in adulthood (more than any other stage), cognitive changes are numerous during this period. In fact, research suggests that adult cognitive development is a complex, ever-changing process that may be even more active than cognitive development in infancy and early childhood (Fischer, Yan, & Stewart, 2003).

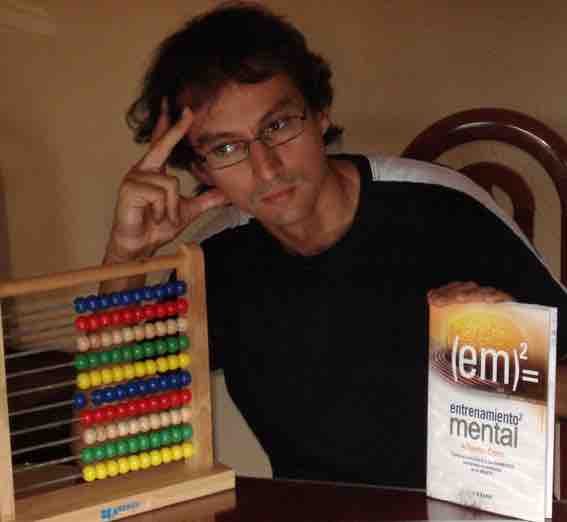

Unlike our physical abilities, which peak in our mid-20s and then begin a slow decline, our cognitive abilities remain relatively steady throughout early and middle adulthood. Research has found that adults who engage in mentally and physically stimulating activities experience less cognitive decline in later adult years and have a reduced incidence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia (Hertzog, Kramer, Wilson, & Lindenberger, 2009; Larson et al., 2006; Podewils et al., 2005).

Beyond Piaget's Theory

According to Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development, the establishment of formal operational thinking occurs during early adolescence and continues through adulthood. Unlike earlier concrete thinking, this kind of thinking is characterized by the ability to think in abstract ways, engage in deductive reasoning, and create hypothetical ideas to explain various concepts.

Since Piaget's theory, other developmental psychologists have suggested a fifth stage of cognitive development, known as postformal operational thinking (Basseches, 1984; Commons & Bresette, 2006; Sinnott, 1998). In postformal thinking, decisions are made based on situations and circumstances, and logic is integrated with emotion as adults develop principles that depend on contexts. This kind of thinking includes the ability to think in dialectics, and differentiates between the ways in which adults and adolescents are able to cognitively handle emotionally charged situations.

Early Adulthood

During early adulthood, cognition begins to stabilize, reaching a peak around the age of 35. Early adulthood is a time of relativistic thinking, in which young people begin to become aware of more than simplistic views of right vs. wrong. They begin to look at ideas and concepts from multiple angles and understand that a question can have more than one right (or wrong) answer. The need for specialization results in pragmatic thinking—using logic to solve real-world problems while accepting contradiction, imperfection, and other issues. Finally, young adults develop a sort of expertise in either education or career, which further enhances problem-solving skills and the capacity for creativity.

Middle Adulthood

Two forms of intelligence—crystallized and fluid—are the main focus of middle adulthood. Our crystallized intelligence is dependent upon accumulated knowledge and experience—it is the information, skills, and strategies we have gathered throughout our lifetime. This kind of intelligence tends to hold steady as we age—in fact, it may even improve. For example, adults show relatively stable to increasing scores on intelligence tests until their mid-30s to mid-50s (Bayley & Oden, 1955). Fluid intelligence, on the other hand, is more dependent on basic information-processing skills and starts to decline even prior to middle adulthood. Cognitive processing speed slows down during this stage of life, as does the ability to solve problems and divide attention. However, practical problem-solving skills tend to increase. These skills are necessary to solve real-world problems and figure out how to best achieve a desired goal.

Intelligence

Cognitive ability changes over the course of a person's lifespan, but keeping the mind engaged and active is the best way to keep thinking sharp.