The expressed powers of the President are those expressed in the Constitution of the United States.

President and Vice President

Article Two of the United States Constitution creates the executive branch of the government, consisting of the president, the vice president, and other executive officers chosen by the president. Clause 1 states that "the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America. He shall hold his Office during the Term of four Years, and, together with the Vice President, chosen for the same Term, be elected, as follows. " Clause one is a "vesting clause," similar to other clauses in Articles 1 and 3, but it vests the power to execute the instructions of Congress, which has the exclusive power to make laws.

Clause 2 states the method for choosing electors in the Electoral College. Under the U.S. Constitution the president and vice president are chosen by electors, under a constitutional grant of authority delegated to the legislatures of the states and the District of Columbia. In other words, the constitution lets the state legislatures decide how electors are created. It does not define or delimit what process a state legislature may use to create its state's college of electors. In practice, since the 1820s, state legislatures have generally chosen to create electors through an indirect popular vote. Each state chooses as many electors as it has Representatives and Senators in Congress. Under the Twenty-third Amendment, the District of Columbia may choose no more electors than the state with the lowest number of electoral votes. Senators, Representatives, or federal officers may not become electors.

Presidential Powers

Perhaps the most important of all presidential powers is commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces. While the power to declare war is constitutionally vested in Congress, the president commands and directs the military and is responsible for planning military strategy. Congress, pursuant to the War Powers Resolution, must authorize any troop deployments longer than 60 days, although that process relies on triggering mechanisms that never have been employed, rendering it ineffectual. Additionally, Congress provides a check on presidential military power through its control over military spending and regulation. While historically presidents initiated the process for going to war, critics have charged that there have been several conflicts in which presidents did not get official declarations, including Theodore Roosevelt's military move into Panama in 1903, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the invasions of Grenada in 1983 and Panama in 1990. The "wars" waged in Iran (2001) and Afghanistan since (2003) are officially called "military engagements" authorized by Congress. Officially, the U.S. was not at war with the governments of those nations, but fought non-government terrorist groups.

Along with the armed forces, the president also directs U.S. foreign policy . Through the Department of State and the Department of Defense, the president is responsible for the protection of Americans abroad and of foreign nationals in the United States. The president decides whether to recognize new nations and new governments, and negotiates treaties with other nations, which become binding on the United States when approved by a two-thirds vote of the Senate .

President Barack Obama meets Prime Minister Stephen Harper

Barack Obama, President of the United States of America, with Stephen Harper, Prime Minister of Canada.

U.S. Foreign Policy Structure

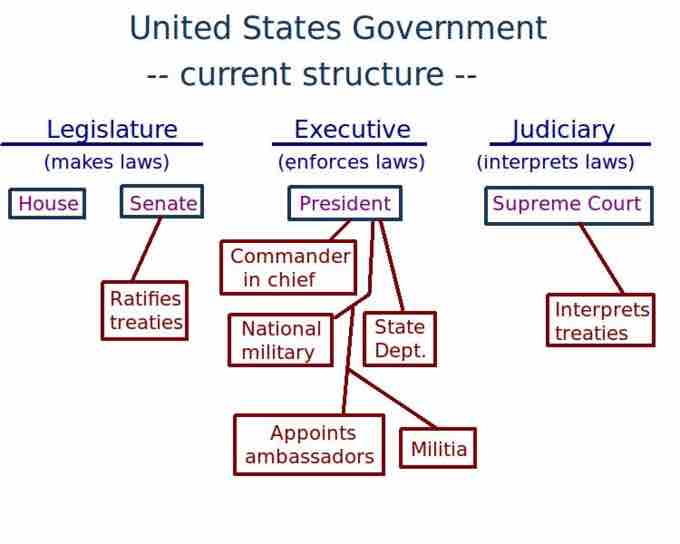

The task of making foreign policy in the United States, according to the United States Constitution, is divided among different branches of government, with the executive branch having much of the decision-making authority, while the Senate ratifies treaties (2/3 vote needed to pass) and the Supreme Court rules on how to interpret treaties. Congress has a role in controlling appropriations for military expenditures.

The president is the head of the executive branch of the federal government and is constitutionally obligated to "take care that the laws be faithfully executed. " Generally, a president may remove purely executive officials at his discretion. However, Congress can curtail and constrain a president's authority to fire commissioners of independent regulatory agencies and certain inferior executive officers by statute. To manage the growing federal bureaucracy, presidents have gradually surrounded themselves with many layers of staff who were eventually organized into the Executive Office of the President of the United States.

The president also has the power to nominate federal judges, including members of the United States courts of appeals and the Supreme Court of the United States. However, these nominations require Senate confirmation. Securing Senate approval can provide a major obstacle for presidents who wish to orient the federal judiciary toward a particular ideological stance. When nominating judges to U.S. district courts, presidents often respect the long-standing tradition of Senatorial courtesy.

The Constitution's Ineligibility Clause prevents the president from simultaneously being a member of Congress. Therefore, the president cannot directly introduce legislative proposals for consideration in Congress. However, the president can take an indirect role in shaping legislation, especially if the president's political party has a majority in one or both houses of Congress. For example, the president or other officials of the executive branch may draft legislation and then ask senators or representatives to introduce these drafts into Congress. The president can further influence the legislative branch through constitutionally mandated, periodic reports to Congress. These reports may be either written or oral, but today are given as the State of the Union address, which often outlines the president's legislative proposals for the coming year.