Dred Scott was born a slave in Virginia and in 1820 was taken by his owner, Peter Blow, to Missouri. In 1832, Blow died and U.S. Army Surgeon Dr. John Emerson purchased Scott. Emerson took him to Fort Armstrong, Illinois, which prohibited slavery in its 1819 constitution. In 1836, Scott was relocated to Fort Snelling, Wisconsin, where slavery was prohibited under the Wisconsin Enabling Act. Scott legally married Harriet Robinson, with the knowledge and consent of Emerson in Fort Snelling.

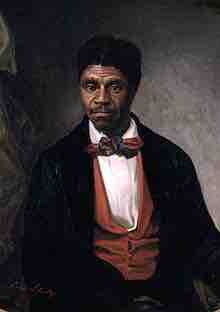

Dred Scott

Dred Scott, the plaintiff in the Dred Scott decision, who sued for his freedom in a Missouri Court.

In 1837, Emerson was ordered to Jefferson Barracks Military Post, south of St. Louis, Missouri. Emerson left Scott and Harriet at Fort Snelling, renting them out for profit. Emerson was reassigned to Fort Jessup, Louisiana, where he married Eliza Sanford. He sent for Scott and Harriet and while en route, Scott's daughter Eliza was born on along the Mississippi River between Iowa and Illinois. By 1840, Emerson's wife, Scott, and Harriet returned to St. Louis while Emerson served in the Seminole War. Emerson left the Army and died in 1843. Eliza inherited his estate and continued to rent Scott out as a slave. In 1846, Scott attempted to purchase his family's freedom, but Eliza refused, prompting Scott to resort to legal action.

Scott sued Emerson for his freedom in a Missouri court in 1846. He received financial assistance from the son of his previous owner, Peter Blow. Scott claimed that his presence and residence in free territories required his emancipation. In June 1847, Scott's case was dismissed because he had failed to provide a witness testifying that he was in fact a slave belonging to Eliza Emerson.

The judge granted Scott a new trial which did not begin until January 1850. While the case awaited trial, Scott and his family were placed in the custody of the St. Louis County Sheriff, who rented out the services of Scott, placing the rents in escrow. The jury found Scott and his family legally free. Emerson appealed to the Supreme Court of Missouri; she had moved to Massachusetts and transferred advocacy of the case to her brother, John F. A. Sanford. November 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the jury's decision, holding the Scotts as legal slaves.

Scott sued in federal court in 1853. The defendant at this point was Sanford, because he was a resident of New York, having returned there in 1853; the federal courts could hear the case under diversity jurisdiction provided in Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution. Judge Robert Wells directed the jury to rely on Missouri law to settle the question of Scott's freedom. Since the Missouri Supreme Court had held Scott was a slave, the jury found in favor of Sanford. Scott then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The decision began by concluding that the Court lacked jurisdiction in the matter because Scott had no standing to sue in Court, as all people of African descent, were found not to be citizens of the United States. The decision is often criticized as being obiter dictum because it went on to conclude that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in federal territories, and slaves could not be taken away from their owners without due process.

The decision was fiercely debated across the country. Abraham Lincoln was able to win the presidential election in 1860 with the hope of stopping the further expansion of slavery. The sons of Peter Blow purchased emancipation for Scott and his family on May 26, 1857. Their freedom was national news and was celebrated in northern cities. Scott worked in a hotel in St. Louis and died of tuberculosis only eighteen months later.

The Dred Scott decision represented a culmination of what was considered a push to expand slavery. Southerners argued that they had a right to bring slaves into the territories, regardless of any decision by a territorial legislature on the subject. The expansion of the territories and resulting admission of new states was a loss of political power for the North. It strengthened Northern slavery opposition, divided the Democratic Party on sectional lines, encouraged secessionist elements among Southern supporters of slavery to make bolder demands, and strengthened the Republican Party.