McCulloch v. Maryland (1819)

On April 8, 1916, Congress passed an act providing the incorporation of the Second Bank of the US. The Bank went into full operation in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and in Baltimore, Maryland in 1817, carrying out business as a branch of the Bank of the US.

On February 11, 1818, the General Assembly of Maryland passed an act placing a tax on all banks not chartered by the legislature. Maryland attempted to impede operations of a branch of the Second Bank of the US by imposing a tax on all bank notes not chartered in Maryland. The Second Bank of the US was the only out-of-state bank in Maryland and the law was perceived to be targeting the US Bank. James McCulloch, head of the Baltimore Branch of the Second Bank of the US, refused to pay the tax.

The lawsuit was filed by John James, an informer seeking to collect half the fine. The case was appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals where the state argued that the Constitution is silent on the subject of banks because the Constitution did not specifically state that the federal government was authorized to charter a bank. The court upheld Maryland and the case was appealed to the Supreme Court.

Both sides of the litigation admitted that the Bank had no authority to establish the Baltimore branch. Chief Justice John Marshall believed that the case established the principles that the Constitution grants Congress implied powers for implementing the Constitution's expressed powers, in order to create a functional national government and that state action may not impede valid constitutional exercises of power by the federal government.

The court determined that Congress had the power to create the Bank . Marshall supported this with four arguments. First, historical practice established Congress' power to create the Bank. Second, he argued that it was the people who ratified the Constitution and thus the people are sovereign, not the states. Third, Marshall admitted that the Constitution does not enumerate a power to create a central bank but that this is not dispositive to Congress' power to establish such an institution. Fourth, he invoked the Necessary and Proper Clause, permitting Congress to seek an objective within its enumerated power so long as it is rationally related to the objective and not forbidden by the Constitution. The Court rejected Maryland's interpretation of the clause and determined that Maryland may not tax the Bank without violating the Constitution.

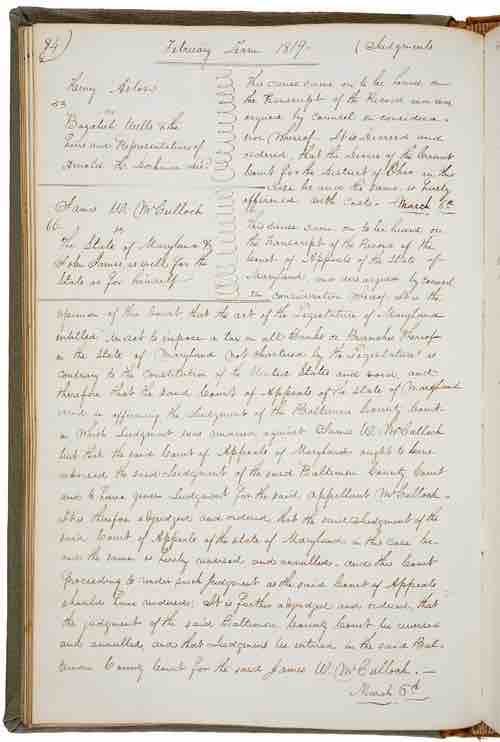

Text of McCulloch v. Maryland decision

Handed down on March 6, 1819, the text of the McCulloch v. Maryland decision appears as recorded in the minutes of the Supreme Court.

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824)

In 1808 The Legislature of New York granted Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton exclusive navigation privileges to waters within the jurisdiction of the state. They petitioned other states and territorial legislatures for similar monopolies, hoping to develop a national network of steamboat lines. Only the Orleans Territory accepted and awarded them a monopoly in the lower Mississippi. Competitors challenged Livingston and Fulton, arguing that the commerce power of the Federal government was exclusive and superseded state laws. In response to legal challenges, they attempted to undercut their rivals by selling them franchises or buying their boats.

Former New Jersey Governor Aaron Ogden tried defying the monopoly, but purchased a license from Livingston and Fulton in 1815 and entered business with Tomas Gibbons from Georgia. The partnership collapsed in 1818 when Gibbons operated another steamboat on Ogden's route between Elizabeth, NJ and New York City, licensed by Congress under a 1793 law regulating coasting trade. They ended up in the New York Court of Errors, which granted a permanent injunction against Gibbons in 1820.

Ogden filed a complaint in the Court of Chancery of New York asking to restrain Gibbons from operating on those waters, contending that states passed laws on issues regarding interstate matters and states should have concurrent power with Congress on matters concerning interstate commerce. Gibbons' lawyer argued that Congress had exclusive national power over interstate commerce according to Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution. The Court of Chancery and the Court of Errors of New York were in favor of Ogden and issued an injunction restricting Gibbons from operating his boats. Gibbons appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the monopoly conflicted with federal law.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gibbons, arguing that the source of Congress' power to promulgate the law was the Commerce Clause. Chief Justice Marshall's ruling determined that a congressional power to regulate navigation is granted. The court went on to conclude that congressional power over commerce should extend to the regulation of all aspects of it.

Barron v. Baltimore (1833)

John Barron co-owned a profitable wharf in the Baltimore harbor and sued the mayor of Baltimore for damages, claiming that when the city had diverted the flow of streams while engaging in street construction, it had created mounds of sand and earth near his wharf making the water too shallow for most vessels. The trail court awarded Barron damages of $4,500, but the appellate court reversed the ruling.

The Supreme Court decided that the Fifth Amendment's guarantee that government takings of private property for public use require just compensation is a restriction upon the federal government. Chief Justice Marshall held that the first ten amendments contain no expression indicating an intention to apply them to the state governments.

The case stated that the freedoms guaranteed by the Bill of Rights did not restrict the state governments. Later Supreme Court rulings would reaffirm this ruling and, beginning in the early 20th century, the Supreme Court used the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to apply most of the Bill of Rights to the states through the process of selective incorporation.