Dual federalism is a theory of federal constitutional law in the United States where governmental power is divided into two separate spheres. One sphere of power belongs to the federal government while the other severally belongs to each constituent state. Under this theory, provisions of the Constitution are interpreted, construed and applied to maximize the authority of each government within its own respective sphere, while simultaneously minimizing, limiting or negating its power within the opposite sphere. Within such jurisprudence, the federal government has authority only where the Constitution so enumerates. The federal government is considered limited generally to those powers listed in the Constitution.

The theory originated within the Jacksonian democracy movement against the mercantilist American system and centralization of government under the Adams administration during the 1820s. With an emphasis on local autonomy and individual liberty, the theory served to unite the principles held by multiple sectional interests; the republican principles of northerners, the pro-slavery ideology of southern planters, and the laissez-faire entrepreneurialism of western interests. President Jackson used the theory as part of his justification in combating the national bank and the Supreme Court moved the law in the direction of dual federalism. The Court used the theory to underpin its rationale in cases where it narrowed the meaning of commerce and expanded state authority through enlarging state police power.

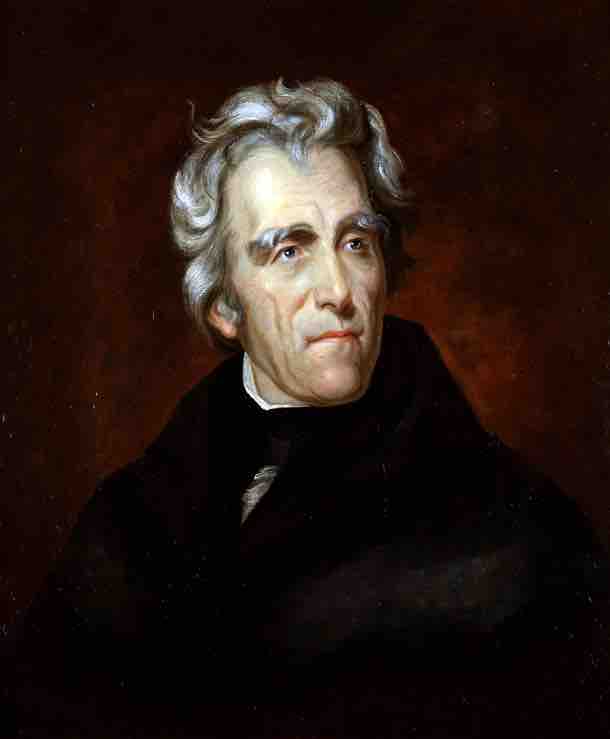

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson, who put forth the theory of dual federalism.

The Democratic-Republicans believed that the Legislative branch had too much power and was unchecked, the Executive branch had too much power and was unchecked, and that a Bill of Rights should be coupled with the Constitution to prevent a dictator from exploiting citizens. The federalists argued that it was impossible to list all the rights, and those that were not listed could be easily overlooked because they were not in the official Bill of Rights.

After the Civil War, the federal government increased in influence greatly on everyday life and in size relative to state governments. The reasons were due to the need to regulate business and industries that span state borders, attempts to secure civil rights, and the provision of social services. National courts now interpret the federal government as the final judge of its own powers under dual federalism.