Introduction

Second-wave feminism is a period of feminist activity. In the United States, second-wave feminism, initially called the Women's Liberation Movement , began during the early 1960s and lasted through the late 1990s. It was a worldwide movement that was strong in Europe and parts of Asia, such as Turkey and Israel, where it began in the 1980s, and it began at other times in other countries.

Women's Liberation March

Women's Liberation march from Farrugut Square to Layfette park

Whereas first-wave feminism focused mainly on suffrage and overturning legal obstacles to gender equality (i.e. voting rights, property rights), second-wave feminism broadened the debate to a wide range of issues: sexuality, family, the workplace, reproductive rights, de facto inequalities, and official legal inequalities. At a time when mainstream women were making job gains in professions, the military, the media, and sports in large part because of second-wave feminist advocacy, second-wave feminism also focused on a battle against violence with proposals for marital rape laws, establishment of rape crisis and battered women's shelters, and changes in custody and divorce law. Its major effort was trying to get the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) added to the United States Constitution, an effort in which they were defeated by anti-feminists led by Phyllis Schlafly, who argued against the ERA, saying women would be drafted into the military.

Historical Precedents

Starting in the late 18th century, and throughout the 19th century, rights, as a concept and claim, gained increasing political, social and philosophical importance in Europe. Movements emerged which demanded freedom of religion, the abolition of slavery, rights for women, rights for those who did not own property and universal suffrage. In the late 18th century the question of women's rights became central to political debates in both France and Britain. At the time some of the greatest thinkers of the Enlightenment, who defended democratic principles of equality and challenged notions that a privileged few should rule over the vast majority of the population, believed that these principles should be applied only to their own gender and their own race.

Overview

The second wave of feminism in North America came as a delayed reaction against the renewed domesticity of women after World War II: the late 1940s post-war boom, which was an era characterized by an unprecedented economic growth, a baby boom, a move to family-oriented suburbs, and the ideal of companionate marriages. This life was clearly illustrated by the media of the time; for example, television shows such as "Father Knows Best" and "Leave It to Beaver" idealized domesticity.

In 1960, the Food and Drug Administration approved the combined oral contraceptive pill, which was made available in 1961. This made it easier for women to have careers without having to leave due to unexpectedly becoming pregnant. The administration of President Kennedy made women's rights a key issue of the New Frontier, and named women (such as Esther Peterson) to many high-ranking posts in his administration.

In 1963 Betty Friedan (), influenced by Simone De Beauvoir's book "The Second Sex," wrote the bestselling book "The Feminine Mystique" in which she explicitly objected to the mainstream media image of women, stating that placing women at home limited their possibilities, and wasted talent and potential. The perfect nuclear family image depicted and strongly marketed at the time, she wrote, did not reflect happiness and was rather degrading for women. This book is widely credited with having begun second-wave feminism.

Betty Friedan (1960)

Betty Friedan, American feminist and writer, wrote the best selling book "The Feminist Mystique. " This book is widely credited with having begun second-wave feminism in the United States.

Achievements

Among the most significant legal victories of the movement after the formation of the National Organization of Women (NOW) were: a 1967 Executive Order extending full Affirmative Action rights to women, Title IX and the Women's Educational Equity Act (1972 and 1974, respectively, educational equality), Title X (1970, health and family planning), the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (1974), the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978, the outlaw of marital rape, the legalization of no-fault divorce, a 1975 law requiring U.S. Military Academies to admit women, and many Supreme Court cases, perhaps most notably Reed v. Reed of 1971 and Roe v. Wade of 1973 . However, the changing of social attitudes towards women is usually considered the greatest success of the women's movement.

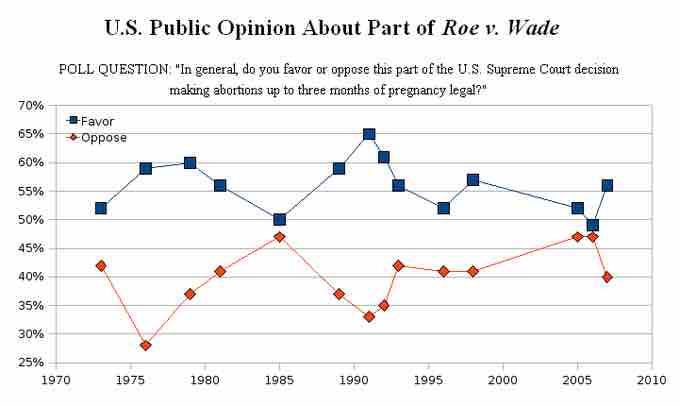

U.S. Public Opinion about Roe v. Wade

Graph showing public support for Roe v. Wade over the years

By the early 1980s, it was largely perceived that women had met their goals and succeeded in changing social attitudes towards gender roles, repealing oppressive laws that were based on sex, integrating "boys' clubs" such as military academies, the United States Armed Forces, NASA, single-sex colleges, men's clubs, and the Supreme Court, and by accomplishing the goal of making gender discrimination illegal. However, the movement did fail, in 1982, in adding the Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution, coming up three states short of ratification.