Fluid balance is the concept of human homeostasis, in that the amount of fluid lost from the body is equal to the amount of fluid taken in. Euvolemia is the state of normal body fluid volume.

Water is necessary for all life on Earth. Humans can survive for four to six weeks without food, but for only a few days without water. The amount of water varies with the individual, as it depends on the condition of the subject, the amount of physical exercise, and on the environmental temperature and humidity.

In the U.S., the reference daily intake (RDI) for water is 3.7 liters per day (l/day) for human males older than 18, and 2.7 l/day for human females older than 18, including water contained in food, beverages, and drinking water.

The common misconception that everyone should drink two liters (68 ounces, or about eight 8 oz. glasses) of water per day is not supported by scientific research. Various reviews of all the scientific literature on the topic performed in 2002 and 2008 could not find any solid scientific evidence that recommended drinking eight glasses of water per day. For example, people in hotter climates will require greater water intake than those in cooler climates.

An individual's thirst provides a better guide for how much water they require rather than a specific, fixed number. A more flexible guideline is that a normal person should urinate at least four times per day, and that the urine should be a light yellow color.

The majority of fluid output occurs via the urine, approximately 1500 ml/day (approx. 1.59 qt/day) in the normal adult resting state.

The body's homeostatic control mechanisms, which maintain a constant internal environment, ensure that a balance between fluid gain and fluid loss is maintained. The hormones ADH (Anti-diuretic hormone, also known as vasopressin) and aldosterone play a major role in this balance.

If the body becomes fluid deficient, there will be an increase in the secretion of these hormones, causing fluid to be retained by the kidneys and urine output to be reduced. Conversely, if fluid levels are excessive, secretion of these hormones is suppressed, less fluid is retained by the kidneys, and there is an increase in the volume of urine produced.

To explain more scientifically: As the body becomes fluid deficient, this is sensed by osmoreceptors in the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis and subfornical organs. These areas project to the supraoptic nucleus and paraventricular nucleus, which contain neurons that secrete the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin from their nerve endings in the posterior pituitary. Thus, there will be an increase in the secretion of antidiuretic hormone that causes fluid to be retained by the kidneys and urine output to be reduced.

A state of fluid insufficiency causes decreased perfusion of the juxtaglomerular apparatus in the kidneys. This activates the renin–angiotensin system; among other actions, it causes renal tubules (i.e., the distal convoluted tubules and the cortical collecting ducts) to reabsorb more sodium and water from the urine. Potassium is secreted into the tubule in exchange for the sodium, which is reabsorbed.

The system then stimulates zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex which, in turn, secretes the hormone aldosterone. This hormone stimulates the reabsorption of sodium ions from distal tubules and collecting ducts. Water in the tubular lumen follows the sodium reabsorption osmotically.

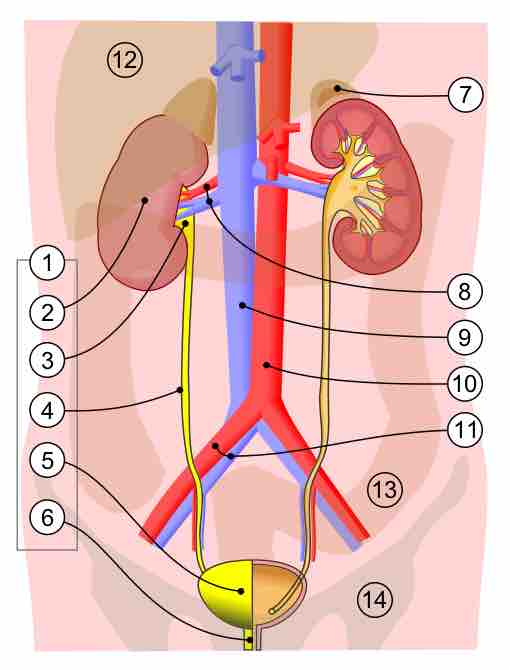

Urinary system

1) Urinary system 2) Kidney 3) Renal pelvis 4) Ureter 5) Urinary bladder 6) Urethra (left side with frontal section) 7) Adrenal gland 8) Renal artery and vein 9) Inferior vena cava 10) Abdominal aorta 11) Common iliac artery and vein 12) Liver 13) Large intestine 14) Pelvis