Lymph transport refers to the transport of lymph fluid from the interstitial space inside the tissues of the body, through the lymph nodes, and into lymph ducts that return the fluid to venous circulation.

Transport in the Lymph Capillaries and Vessels

Lymphatic capillaries are the site of lymph fluid collection from the tissues. The fluid accumulates in the interstitial space inside tissues after leaking out through the cardiovascular capillaries. The fluid enters the lymphatic capillaries by leaking through the minivalves located in the junctions of the endothelium. Under ordinary conditions these minivalves prevent the lymph from flowing back into the tissues. In addition to interstitial fluid, pathogens, proteins, and tumor cells may also leak into the lymph capillaries and be transported through lymph.

The lymph capillaries feed into larger lymph vessels. The lymph vessels that receive lymph fluid from many capillaries are called collecting vessels. Semilunar valves work together with smooth muscle contractions and skeletal muscle pressure to slowly push the lymph fluid forward while the valves prevent backflow. The collecting vessels typically transport lymph fluid either into lymph nodes or lymph trunks.

Transport Within Lymph Nodes

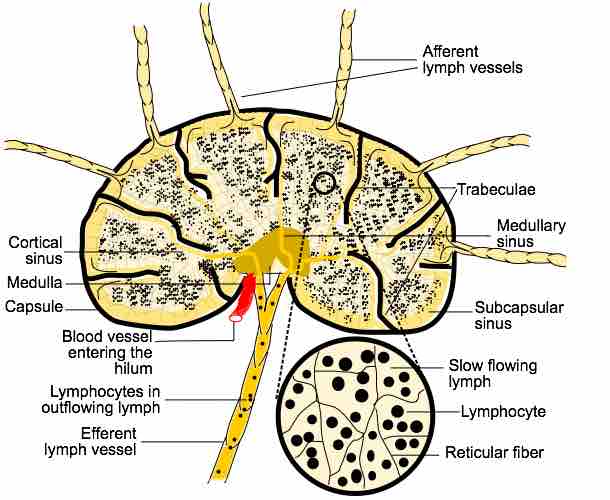

Lymph circulates to the lymph node via afferent lymphatic vessels. The lymph fluid drains into the node just beneath the capsule of the node into its various sinus spaces. These spaces are loosely separated by walls, so lymph fluid flows around them throughout the lymph node.

The sinus space is filled with macrophages that engulf foreign particles and pathogens and filter the lymph. The sinuses converge at the hilum of the node, where lymph then leaves the node via an efferent lymphatic vessel toward either a more central lymph node or a lymph duct for drainage into one of the subclavian veins.

The lymph nodes contain a large number of B and T lymphocytes, which are transported throughout the node during many components of the adaptive immune response. When a lymphocyte is presented with an antigen (such as by an activated helper T cell), B cells become activated and migrate to the germinal centers of the node, where they proliferate and differentiate to be specific to that antigen. When antibody-producing B cells are formed, they migrate to the medullary (central) cords of the node. Stimulation of the lymphocytes by antigens can accelerate the migration process to about ten times normal, resulting in the characteristic swelling of the lymph nodes that is a common symptom of many infections. The lymphocytes are transported through lymph fluid and leave the node through the efferent vessels to travel to other parts of the body to perform adaptive immune response functions.

Flow of Lymph

The lymph flows from the afferent vessels into the sinuses of the lymph node, and then out of the node through the efferent vessels.

The End of Lymphatic Transport

After leaving the lymph node through efferent vessels, lymph travels either to another node further into the body or to a lymph trunk, the larger vessel where many efferent vessels converge. Four pairs of lymph trunks are distributed laterally around the center of the body, along with an unpaired intestinal trunk.

The lymph trunks then converge into the two lymph ducts, the right lymph duct and the thoracic duct. These ducts take the lymph into the right and left subclavian veins, which flow into the vena cava. This is where lymph fluid reaches the end of its journey from the interstitial space of tissues back into blood circulation.